Before studying each book, read these short articles that give an introduction and background. In each article, the reader will find information regarding authorship, historical background, theological themes, and a teaching rotation. Additionally, the reader will find a series of discovery questions that are helpful for teaching and leading discussion. To teach through these books, make sure to read through our earlier article on “Inductive Bible Study.”

Before studying each book, read these short articles that give an introduction and background. In each article, the reader will find information regarding authorship, historical background, theological themes, and a teaching rotation. Additionally, the reader will find a series of discovery questions that are helpful for teaching and leading discussion. To teach through these books, make sure to read through our earlier article on “Inductive Bible Study.”

These articles might be helpful for personal Bible study or for teaching through these books. In each article below, we offer a thorough discussion of:

- Authorship

- Date

- Audience

- Historical background

- Bible difficulties

- Critical scholarship

- Verse by verse commentary

This will really be an ongoing, lifelong project. As we continue to read, study, and teach through the Old Testament, we will continue to develop and add to the material in each article.

This will really be an ongoing, lifelong project. As we continue to read, study, and teach through the Old Testament, we will continue to develop and add to the material in each article.

Ultimately, the authority and exegesis of the text drives the interpretation of these commentaries. We agree with Charles Spurgeon when he said that he would rather be wrong about his systematic theology, than contradict the clear teaching Scripture.[1] At the same time, we feel that systematic theology and exegetical theology are not enemies, but allies. That is, these two disciplines (done well) serve to correct one another: We cannot have the part without the whole, nor the whole without the part. For our work in systematic theology, see our work “Systematic Theology.”

Be prepared to scroll! Some of these articles are over a hundred pages long, so you’ll need to scroll down to find whatever passage you’re looking for. We have listed the verses in BOLD to make it easier to find a given passage.

Genesis

This is a book about beginnings: The beginning of the universe, the human race, and the nation of Israel. We also see God respond to the Fall of humanity by enacting his plan through the nation of Israel.

This is a book about beginnings: The beginning of the universe, the human race, and the nation of Israel. We also see God respond to the Fall of humanity by enacting his plan through the nation of Israel.

Exodus

This is a book about God’s rescue. It demonstrates how God freed the Jewish people from the evil tyranny of a foreign king—the Egyptian Pharaoh—and they are led toward the Promised Land. It serves as a picture of how God rescues his people in the New Testament through Jesus.

This is a book about God’s rescue. It demonstrates how God freed the Jewish people from the evil tyranny of a foreign king—the Egyptian Pharaoh—and they are led toward the Promised Land. It serves as a picture of how God rescues his people in the New Testament through Jesus.

Leviticus

While Exodus is a book of rescue, Leviticus is a book of holiness. It has been said, “It took one night to get the Jews out of Egypt, but forty years to get the Egypt out of them.” Leviticus explains the ceremonial, civil, and moral laws given to Israel. We discover many themes in Leviticus: being distinct from the nations, the need for blood to make atonement for sin, the perfection of the sacred offerings, and establishment of the priesthood. These themes point forward to finished work of Christ, whose blood and sacrifice completely paid for all of our sins.

While Exodus is a book of rescue, Leviticus is a book of holiness. It has been said, “It took one night to get the Jews out of Egypt, but forty years to get the Egypt out of them.” Leviticus explains the ceremonial, civil, and moral laws given to Israel. We discover many themes in Leviticus: being distinct from the nations, the need for blood to make atonement for sin, the perfection of the sacred offerings, and establishment of the priesthood. These themes point forward to finished work of Christ, whose blood and sacrifice completely paid for all of our sins.

Numbers

This book explains why the Jews needed to wander for 40 years in the wilderness: When the spies reconnoitered the land, they came back in fear regarding the people of the land. While God had promised them the land, they were too afraid to take over what God had promised. The Hebrew title for this book (Bemiḏbār) is translated “in the wilderness,” while the Greek title (Arithmoi, think “arithmetic”) is translated as “numbers.” In our estimation, the Hebrew title captures the major contents of the book better, because there is more narrative in this book compared to Leviticus and Deuteronomy, and much of it relates to the 40 year Wilderness Wandering.

This book explains why the Jews needed to wander for 40 years in the wilderness: When the spies reconnoitered the land, they came back in fear regarding the people of the land. While God had promised them the land, they were too afraid to take over what God had promised. The Hebrew title for this book (Bemiḏbār) is translated “in the wilderness,” while the Greek title (Arithmoi, think “arithmetic”) is translated as “numbers.” In our estimation, the Hebrew title captures the major contents of the book better, because there is more narrative in this book compared to Leviticus and Deuteronomy, and much of it relates to the 40 year Wilderness Wandering.

Deuteronomy

The name “Deuteronomy” comes from the words deutero (“second”) and nomos (“law”). After the 40 year Wilderness Wandering (Deut. 1:3), Moses repeats the Law to the second generation, so this is a good title for the book. Historically, however, the title came from the Greek translation of the OT (the Septuagint or LXX), which rendered Deuteronomy 17:18 as “a copy of this law” with “a repetition of this law.” Jewish readers title this book by its first words (“These are the words”) or by Deuteronomy 17:18 (“a copy of this law”). The events of Deuteronomy take place at the tail end of the 40 year wandering. Since an entire new generation had come forward during this time, Moses needed to repeat the law to them (since none of them were there when it was originally given). Moses dies, and he passes the baton to Joshua, who takes them into the Promised Land.

The name “Deuteronomy” comes from the words deutero (“second”) and nomos (“law”). After the 40 year Wilderness Wandering (Deut. 1:3), Moses repeats the Law to the second generation, so this is a good title for the book. Historically, however, the title came from the Greek translation of the OT (the Septuagint or LXX), which rendered Deuteronomy 17:18 as “a copy of this law” with “a repetition of this law.” Jewish readers title this book by its first words (“These are the words”) or by Deuteronomy 17:18 (“a copy of this law”). The events of Deuteronomy take place at the tail end of the 40 year wandering. Since an entire new generation had come forward during this time, Moses needed to repeat the law to them (since none of them were there when it was originally given). Moses dies, and he passes the baton to Joshua, who takes them into the Promised Land.

Joshua

Joshua

This book is about the military takeover of the Promised Land. After 40 years of anticipation, the Jews finally take over what was promised to them. Joshua is a book of war, bloodshed, and battle. It is also a book that connects the promises of God made in the time of Abraham (Gen. 15:13-16) with the rest of biblical history.

Judges

This book begins with the death of Joshua. In the absence of strong leadership, the nation falls into moral and spiritual anarchy fairly quickly. Judges contains a constant cycle of rejection, ramifications, repentance, and rescue. Modern people typically think of “judges” as men in robes who preside over legal cases. While the judges of Israel did adjudicate legal disputes, their primary function was to serve as leaders or “deliverers,” who rescued Israel from apostasy and judgment: “Then the Lord raised up judges who delivered them from the hands of those who plundered them” (Judg. 2:16). God is the ultimate “Judge” (šôpēṭ) who ruled the nation (Judg. 11:27), but he sovereignly worked through these ad hoc leaders to deliver the nation of Israel.

This book begins with the death of Joshua. In the absence of strong leadership, the nation falls into moral and spiritual anarchy fairly quickly. Judges contains a constant cycle of rejection, ramifications, repentance, and rescue. Modern people typically think of “judges” as men in robes who preside over legal cases. While the judges of Israel did adjudicate legal disputes, their primary function was to serve as leaders or “deliverers,” who rescued Israel from apostasy and judgment: “Then the Lord raised up judges who delivered them from the hands of those who plundered them” (Judg. 2:16). God is the ultimate “Judge” (šôpēṭ) who ruled the nation (Judg. 11:27), but he sovereignly worked through these ad hoc leaders to deliver the nation of Israel.

Ruth

This book tells the story of King David’s great-grandmother, Ruth. It takes place during the time of Judges, and it is a love story about a Moabitess widow who marries a good man, Boaz. On one level, this book is a short story about a romance between Ruth and Boaz. However, at the end of the book, we discover that their marriage brings about the most important king in Israel’s history: King David. During the time of the Judges, it appears that God is relatively inactive. One might wonder what he was doing. However, in the book of Ruth, we discover that God was preparing the lineage of Israel’s greatest king, who would pull Israel out of this time of chaos and anarchy. Furthermore, King David is the ancestor of Jesus of Nazareth, who would later pull the world out of its chaos and anarchy due to sin.

This book tells the story of King David’s great-grandmother, Ruth. It takes place during the time of Judges, and it is a love story about a Moabitess widow who marries a good man, Boaz. On one level, this book is a short story about a romance between Ruth and Boaz. However, at the end of the book, we discover that their marriage brings about the most important king in Israel’s history: King David. During the time of the Judges, it appears that God is relatively inactive. One might wonder what he was doing. However, in the book of Ruth, we discover that God was preparing the lineage of Israel’s greatest king, who would pull Israel out of this time of chaos and anarchy. Furthermore, King David is the ancestor of Jesus of Nazareth, who would later pull the world out of its chaos and anarchy due to sin.

1 & 2 Samuel

The original Hebrew Bible contained 1 and 2 Samuel as one book—not two. However, because these scrolls were so massive and cumbersome, the books were later separated into two books. These two books explain (1) the rise of the monarchy in Israel, (2) the importance of the prophets in Israel, the arrival of King David—Israel’s prototypical king, and (4) the Davidic Covenant which will be fulfilled by the “greater David,” who is Jesus the Messiah.

The original Hebrew Bible contained 1 and 2 Samuel as one book—not two. However, because these scrolls were so massive and cumbersome, the books were later separated into two books. These two books explain (1) the rise of the monarchy in Israel, (2) the importance of the prophets in Israel, the arrival of King David—Israel’s prototypical king, and (4) the Davidic Covenant which will be fulfilled by the “greater David,” who is Jesus the Messiah.

1 & 2 Kings

These two books explain how we get from the death of David (in a united monarchy—970 BC), to a Temple system (under Solomon), to a split kingdom (under Jeroboam and Rehoboam), to the exile in Babylon (in 587 BC). The account demonstrates that the nation would rise or fall based on their loyalty to God’s covenant with them. Thus, these books give us two views of history—both human and divine.

These two books explain how we get from the death of David (in a united monarchy—970 BC), to a Temple system (under Solomon), to a split kingdom (under Jeroboam and Rehoboam), to the exile in Babylon (in 587 BC). The account demonstrates that the nation would rise or fall based on their loyalty to God’s covenant with them. Thus, these books give us two views of history—both human and divine.

1 and 2 Chronicles

The Hebrew title for 1 and 2 Chronicles is “the accounts of the days” or “the words of the days” (Diḇerê hāyyāmɩ̂m). The Chronicler recounts biblical history from the beginning of the human race all the way until the Babylonian Exile and edict to restore the Temple. He focuses his attention on the kings of Judah, rather than Israel. Jewish tradition states that Ezra wrote these books (Baba Bathra, 15a). 1 and 2 Kings ends in defeat, but the Chronicles were written after Kings and after the edict to restore the Temple. One of the messages of the book is that faith leads to success (2 Chron. 20:20, 22). The book focuses on the kings of Judah.

The Hebrew title for 1 and 2 Chronicles is “the accounts of the days” or “the words of the days” (Diḇerê hāyyāmɩ̂m). The Chronicler recounts biblical history from the beginning of the human race all the way until the Babylonian Exile and edict to restore the Temple. He focuses his attention on the kings of Judah, rather than Israel. Jewish tradition states that Ezra wrote these books (Baba Bathra, 15a). 1 and 2 Kings ends in defeat, but the Chronicles were written after Kings and after the edict to restore the Temple. One of the messages of the book is that faith leads to success (2 Chron. 20:20, 22). The book focuses on the kings of Judah.

Ezra

Ezra picks up after the Babylonian Exile. The book of Kings ends with the Jewish people being taken into Exile (587-586 BC). Ezra and Nehemiah describe how the Jewish people regathered into their land, rebuilt the second Temple, and reformed their nation against all odds. Even though many Jews existed at this time, only a “remnant” of 50,000 returned (Ezra 2:64ff; cf. Isa. 10:22). Ezra is the most likely author of this book. Jewish tradition held that Ezra wrote 1 and 2 Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah (Baba Bathra 15a). He was the descendant of Aaron the high priest, and therefore, he was from a priestly class (Ezra 7:5). He was “well versed” in the Bible, and therefore, literate and scholarly (v.6).

Ezra picks up after the Babylonian Exile. The book of Kings ends with the Jewish people being taken into Exile (587-586 BC). Ezra and Nehemiah describe how the Jewish people regathered into their land, rebuilt the second Temple, and reformed their nation against all odds. Even though many Jews existed at this time, only a “remnant” of 50,000 returned (Ezra 2:64ff; cf. Isa. 10:22). Ezra is the most likely author of this book. Jewish tradition held that Ezra wrote 1 and 2 Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah (Baba Bathra 15a). He was the descendant of Aaron the high priest, and therefore, he was from a priestly class (Ezra 7:5). He was “well versed” in the Bible, and therefore, literate and scholarly (v.6).

Nehemiah

While Ezra describes how God restored his spiritual kingdom (e.g. the Temple, the scribes, etc.), Nehemiah describes how God restored his political kingdom to Israel (e.g. the wall, the defenses, the city, etc.). These books explain how the Jews got back into their land, restored their collective faith, and repaired their city walls from their enemies.

While Ezra describes how God restored his spiritual kingdom (e.g. the Temple, the scribes, etc.), Nehemiah describes how God restored his political kingdom to Israel (e.g. the wall, the defenses, the city, etc.). These books explain how the Jews got back into their land, restored their collective faith, and repaired their city walls from their enemies.

Esther

This book answers the question of what happened to the Jews who didn’t return from the exile (with Ezra and Nehemiah). It shows God’s sovereign protection over his people from their evil enemies who are trying to wipe them out. Despite the fact that the book of Esther never mentions God’s name, his sovereign plan for Esther and the Jewish people fills this short book.

This book answers the question of what happened to the Jews who didn’t return from the exile (with Ezra and Nehemiah). It shows God’s sovereign protection over his people from their evil enemies who are trying to wipe them out. Despite the fact that the book of Esther never mentions God’s name, his sovereign plan for Esther and the Jewish people fills this short book.

Job

This might be our earliest book in the Hebrew canon. The setting for the book is a cosmic debate. Satan—frustrated in his attempts to attack God—has moved to Earth to attack those whom God loves: humanity. Like a mafia crime boss, he knows that if he can’t get to God, then he should try to get to his family, his children. Satan accuses the humans of being righteous for self-service. “Take away the blessings,” says Satan, “and these humans will hate you.” If loving God for his blessings is wrong, then even the godliest of men will be the most sinful! Once this accusation is raised, it needs to be defeated, not destroyed.

This might be our earliest book in the Hebrew canon. The setting for the book is a cosmic debate. Satan—frustrated in his attempts to attack God—has moved to Earth to attack those whom God loves: humanity. Like a mafia crime boss, he knows that if he can’t get to God, then he should try to get to his family, his children. Satan accuses the humans of being righteous for self-service. “Take away the blessings,” says Satan, “and these humans will hate you.” If loving God for his blessings is wrong, then even the godliest of men will be the most sinful! Once this accusation is raised, it needs to be defeated, not destroyed.

Psalms

The NT cites the Psalms 116 times. (Isaiah is the only book cited more than the Psalms.) As followers of Christ, we should immerse ourselves in the book that Jesus and his disciples were absorbed in. David wrote roughly half of the Psalms. In his writings, we see inside the soul of a “man after God’s own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14). The psalms are not dry theological treatises. Instead, these songs come from a place deep inside of David and the other psalmists. The Psalms are books of poetry and music were written from the time of the Exodus (Ps. 90) to the time of the Exile (Ps. 137). They teach us how to give thanks, be wise, offer lament, and love God’s attributes and word.

The NT cites the Psalms 116 times. (Isaiah is the only book cited more than the Psalms.) As followers of Christ, we should immerse ourselves in the book that Jesus and his disciples were absorbed in. David wrote roughly half of the Psalms. In his writings, we see inside the soul of a “man after God’s own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14). The psalms are not dry theological treatises. Instead, these songs come from a place deep inside of David and the other psalmists. The Psalms are books of poetry and music were written from the time of the Exodus (Ps. 90) to the time of the Exile (Ps. 137). They teach us how to give thanks, be wise, offer lament, and love God’s attributes and word.

Proverbs

Solomon seems to have written the majority of the Proverbs (Prov. 1:1; 10:1; 25:1), which is a book of wisdom—that is, learning to live skillfully. The term “proverb” comes from the Latin term proverbium, which is composed of the roots pro (“instead of”) and verbum (“words”). In short, a proverb is a short, pithy, memorable statement that says a lot in a short amount of words. In our culture, we are awash in a flood of information, but we are starving for wisdom. We have trivia and facts at our fingertips, but are we living any better? Wisdom is the ability to know how to use the knowledge that we possess. Wisdom is the big picture, rather than just endless details.

Solomon seems to have written the majority of the Proverbs (Prov. 1:1; 10:1; 25:1), which is a book of wisdom—that is, learning to live skillfully. The term “proverb” comes from the Latin term proverbium, which is composed of the roots pro (“instead of”) and verbum (“words”). In short, a proverb is a short, pithy, memorable statement that says a lot in a short amount of words. In our culture, we are awash in a flood of information, but we are starving for wisdom. We have trivia and facts at our fingertips, but are we living any better? Wisdom is the ability to know how to use the knowledge that we possess. Wisdom is the big picture, rather than just endless details.

Ecclesiastes

In the Proverbs, Solomon writes what life is like with God. But in Ecclesiastes, he writes about what it is like to reject God. Since Solomon had tried out both perspectives, he is eminently qualified to write on these topics. At points, Ecclesiastes reads like a modern piece of atheistic existential literature. But this is because Solomon is trying to engage his readers with the folly and uselessness of living apart from God. However, to be clear, Solomon was no atheist. He speaks of God roughly 40 times throughout the book, and he mentions the “fear of God” several times (3:14; 5:7; 7:18; 8:12-13; 12:13). In fact, the conclusion to the book is that life is meaningful and valuable when we factor God into the picture (Eccl. 12:10-14).

In the Proverbs, Solomon writes what life is like with God. But in Ecclesiastes, he writes about what it is like to reject God. Since Solomon had tried out both perspectives, he is eminently qualified to write on these topics. At points, Ecclesiastes reads like a modern piece of atheistic existential literature. But this is because Solomon is trying to engage his readers with the folly and uselessness of living apart from God. However, to be clear, Solomon was no atheist. He speaks of God roughly 40 times throughout the book, and he mentions the “fear of God” several times (3:14; 5:7; 7:18; 8:12-13; 12:13). In fact, the conclusion to the book is that life is meaningful and valuable when we factor God into the picture (Eccl. 12:10-14).

Song of Solomon

This book is also called the “Song of Songs,” because this is the title attributed to it in the Hebrew (Šɩ̂r haš-šɩ̄rɩ̂m). The Latin version titles it the “Canticles” (canticum). English translations render it as “Song of Songs” or “Song of Solomon.” King Solomon wrote this book about his relationship with his wife. The contents of this little book will no doubt surprise prudish readers, as it describes the depths of biblical love, sex, and marriage.

This book is also called the “Song of Songs,” because this is the title attributed to it in the Hebrew (Šɩ̂r haš-šɩ̄rɩ̂m). The Latin version titles it the “Canticles” (canticum). English translations render it as “Song of Songs” or “Song of Solomon.” King Solomon wrote this book about his relationship with his wife. The contents of this little book will no doubt surprise prudish readers, as it describes the depths of biblical love, sex, and marriage.

Isaiah

The book of Isaiah is one of the longest books in the Bible (third only to Jeremiah and the Psalms). It is also the book most quoted OT by the NT authors. In fact, 194 NT passages quote from Isaiah, citing or alluding to 54 of the 66 chapters of the book. Some scholars have referred to it as the “fifth gospel,” because it gives us such unique information about the person of Christ. Isaiah gives us incredible predictions about the person of Jesus, as well as a broad scope of God’s plan for Israel before, during, and after the Exile—even into the New Heavens and Earth.

The book of Isaiah is one of the longest books in the Bible (third only to Jeremiah and the Psalms). It is also the book most quoted OT by the NT authors. In fact, 194 NT passages quote from Isaiah, citing or alluding to 54 of the 66 chapters of the book. Some scholars have referred to it as the “fifth gospel,” because it gives us such unique information about the person of Christ. Isaiah gives us incredible predictions about the person of Jesus, as well as a broad scope of God’s plan for Israel before, during, and after the Exile—even into the New Heavens and Earth.

Jeremiah

Jeremiah is the longest prophetic book in the Bible, and the second longest book in the OT (besides Psalms). Jeremiah also holds the record for having the longest prophetic ministry. He was called to his ministry in 626 BC and continued to preach through the Babylonian exile in 586 BC down to about 582 BC, a ministry of some 45 years. Jeremiah seems like a sensitive temperament. He is called the “weeping prophet” for a reason (Jer. 9:1)! Yet God allowed him to go through considerable verbal and physical attack, undergoing more recorded persecution than any other OT prophet. Despite his sensitive nature, he persevered boldly through God’s empowerment, and God turned him into a “tower of bronze” (Jer. 1:18).

Jeremiah is the longest prophetic book in the Bible, and the second longest book in the OT (besides Psalms). Jeremiah also holds the record for having the longest prophetic ministry. He was called to his ministry in 626 BC and continued to preach through the Babylonian exile in 586 BC down to about 582 BC, a ministry of some 45 years. Jeremiah seems like a sensitive temperament. He is called the “weeping prophet” for a reason (Jer. 9:1)! Yet God allowed him to go through considerable verbal and physical attack, undergoing more recorded persecution than any other OT prophet. Despite his sensitive nature, he persevered boldly through God’s empowerment, and God turned him into a “tower of bronze” (Jer. 1:18).

Lamentations

This book was written after the exile (Lam. 1:5). Israel is personified as a weeping woman. The purpose of this book is to show the fallout of the Babylonian captivity. God judged Israel for her sins (Lam. 1:5). He compares her to a filthy prostitute (Lam. 1:9). Woman are cannibalizing their own children, because they are so starving (Lam. 2:20; 4:10). God will still love Israel (Lam. 3:22). He calls for God to judge the nations for their sin (Lam. 3:64). He compares their judgment to Sodom and Gomorrah. He will bring the Jews back (Lam. 4:22). He prays that God will bring them back and forgive them (Lam. 5:21-22).

This book was written after the exile (Lam. 1:5). Israel is personified as a weeping woman. The purpose of this book is to show the fallout of the Babylonian captivity. God judged Israel for her sins (Lam. 1:5). He compares her to a filthy prostitute (Lam. 1:9). Woman are cannibalizing their own children, because they are so starving (Lam. 2:20; 4:10). God will still love Israel (Lam. 3:22). He calls for God to judge the nations for their sin (Lam. 3:64). He compares their judgment to Sodom and Gomorrah. He will bring the Jews back (Lam. 4:22). He prays that God will bring them back and forgive them (Lam. 5:21-22).

Ezekiel

God told him that the people would not listen to him (Ezek. 3:7), but he was willing to preach to Jerusalem during the Exile anyhow. Ezekiel’s name means “God strengthens.” His book is one of the most chronological in the entire Bible, which makes it easier to study. He was from a priestly family, and he was called to be a prophet at about the age of 30 in ~593 BC (Ezek. 1:1). He gave his last oracle in the 27th year of King Jehoichin (Ezek. 29:17), which gave him a 23 year ministry.

God told him that the people would not listen to him (Ezek. 3:7), but he was willing to preach to Jerusalem during the Exile anyhow. Ezekiel’s name means “God strengthens.” His book is one of the most chronological in the entire Bible, which makes it easier to study. He was from a priestly family, and he was called to be a prophet at about the age of 30 in ~593 BC (Ezek. 1:1). He gave his last oracle in the 27th year of King Jehoichin (Ezek. 29:17), which gave him a 23 year ministry.

Daniel

This book explains the Exile from the perspective of Daniel, who was taken captive with his friends to be brainwashed young viceroys for the Babylon Empire. This book strategically shows how to conduct ourselves in a pagan culture. It also gives extensive prophecies about the end of human history.

This book explains the Exile from the perspective of Daniel, who was taken captive with his friends to be brainwashed young viceroys for the Babylon Empire. This book strategically shows how to conduct ourselves in a pagan culture. It also gives extensive prophecies about the end of human history.

Hosea

Hosea’s name literally means “salvation.” The purpose of his ministry was to call the Northern Kingdom (Israel) to repentance by following the covenant. Hosea was asked to marry an adulterous woman (Gomer), so he can experience God’s pain in Israel’s idolatry and adulterous actions. Hosea preached repentance before the destruction of the Northern Kingdom (Israel) by the Assyrians in 722 BC.

Hosea’s name literally means “salvation.” The purpose of his ministry was to call the Northern Kingdom (Israel) to repentance by following the covenant. Hosea was asked to marry an adulterous woman (Gomer), so he can experience God’s pain in Israel’s idolatry and adulterous actions. Hosea preached repentance before the destruction of the Northern Kingdom (Israel) by the Assyrians in 722 BC.

Joel

Joel (Hebrew Yo ‘el) means “Yahweh is God.” He served in the southern kingdom of Judah in the eighth century (before the fall of Israel in the north). He gives a prophecy of an army of locusts who come to destroy the crops of Israel. However, this prophecy morphs into an actual army of Assyrian soldiers who come to destroy Israel. Later, his prophecy morphs even further to describe the great and terrible “Day of the Lord,” where God will judge all nations in the Tribulation. By the end of the book, Joel pictures God defending Israel like a powerful lion. The nation’s protection and security come from God.

Joel (Hebrew Yo ‘el) means “Yahweh is God.” He served in the southern kingdom of Judah in the eighth century (before the fall of Israel in the north). He gives a prophecy of an army of locusts who come to destroy the crops of Israel. However, this prophecy morphs into an actual army of Assyrian soldiers who come to destroy Israel. Later, his prophecy morphs even further to describe the great and terrible “Day of the Lord,” where God will judge all nations in the Tribulation. By the end of the book, Joel pictures God defending Israel like a powerful lion. The nation’s protection and security come from God.

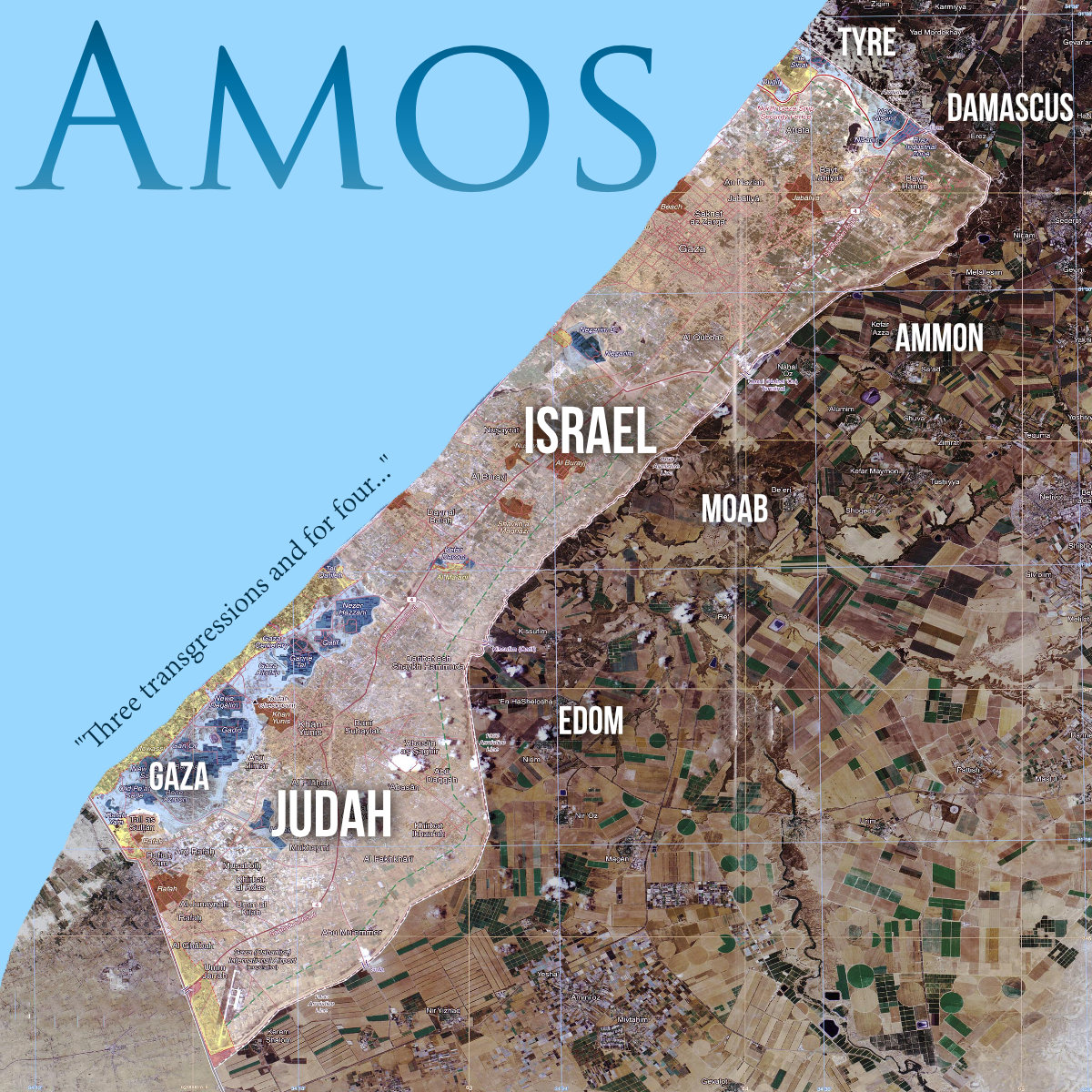

Amos

Amos’ name most likely means “burden-bearer.” He served in the eighth century in the Northern Kingdom (Israel), though he also lived in Tekoa (Amos 1:1), which was a city ten miles south of Jerusalem. The city rested on the Judean range where Amos was a herdsman by trade (Amos 1:1; 7:14). Since his father is never mentioned, he could’ve come from humble backgrounds. Even though he was never formally trained as a prophet, he responded to God’s call to go speak to his people. Amos himself said, “I am not a prophet, nor am I the son of a prophet; for I am a herdsman and a grower of sycamore figs. 15 But the LORD took me from following the flock and the LORD said to me, ‘Go prophesy to My people Israel (Amos 7:14-15). Amos starts by explaining God’s judgment for the evil surrounding nations, but then turns on Israel by explaining God’s judgment for them as well! He also explains that they can’t trust in the Temple sacrifices when they are living entirely contrary to the covenant. It ends with the destruction of the Temple, but also with a hopeful message that the Temple will one day be rebuilt.

Amos’ name most likely means “burden-bearer.” He served in the eighth century in the Northern Kingdom (Israel), though he also lived in Tekoa (Amos 1:1), which was a city ten miles south of Jerusalem. The city rested on the Judean range where Amos was a herdsman by trade (Amos 1:1; 7:14). Since his father is never mentioned, he could’ve come from humble backgrounds. Even though he was never formally trained as a prophet, he responded to God’s call to go speak to his people. Amos himself said, “I am not a prophet, nor am I the son of a prophet; for I am a herdsman and a grower of sycamore figs. 15 But the LORD took me from following the flock and the LORD said to me, ‘Go prophesy to My people Israel (Amos 7:14-15). Amos starts by explaining God’s judgment for the evil surrounding nations, but then turns on Israel by explaining God’s judgment for them as well! He also explains that they can’t trust in the Temple sacrifices when they are living entirely contrary to the covenant. It ends with the destruction of the Temple, but also with a hopeful message that the Temple will one day be rebuilt.

Obadiah

The focus of the book is the destruction of Edom (v.1). The city of Edom was embedded in a mountain fortress, which seemed impenetrable. But in the seventh century AD, Edom was conquered by Muslim warriors (AD 636). Today, it is a place for tourists. It has never been rebuilt. Obadiah gives this prophecy to Edom, because Jerusalem’s destruction is imminent. He warns them not to overdo Jerusalem’s judgment, or God will bring the same to them. This is the shortest book in the OT, which makes it difficult to date. Some place it as early as the ninth century (under Jehoram) or as late as the sixth century (after the destruction of Jerusalem). It is very difficult to know which Obadiah wrote this book, because the name is given to at least twelve other OT characters.

The focus of the book is the destruction of Edom (v.1). The city of Edom was embedded in a mountain fortress, which seemed impenetrable. But in the seventh century AD, Edom was conquered by Muslim warriors (AD 636). Today, it is a place for tourists. It has never been rebuilt. Obadiah gives this prophecy to Edom, because Jerusalem’s destruction is imminent. He warns them not to overdo Jerusalem’s judgment, or God will bring the same to them. This is the shortest book in the OT, which makes it difficult to date. Some place it as early as the ninth century (under Jehoram) or as late as the sixth century (after the destruction of Jerusalem). It is very difficult to know which Obadiah wrote this book, because the name is given to at least twelve other OT characters.

Jonah

Jonah himself was most likely the author of this book, writing it towards the end of his life. Jonah is mentioned only once in the OT in the book of 2 Kings (2 Kings 14:25). There we learn that Jonah is from Gath-Hepher (in Zebulan) and that he was likely a contemporary of Jeroboam II (782-753 BC). Therefore, Jonah might fit into the period between the reigns of Adad-Nirari II (810-783 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser II (745 BC). So, we might date the book somewhere between 800 and 750 BC. The story of Jonah shows the reluctance of a prophet to spread God’s mercy on the evil Assyrians living in Nineveh. It shows the incredible mercy of God on the most unlikely of people.

Jonah himself was most likely the author of this book, writing it towards the end of his life. Jonah is mentioned only once in the OT in the book of 2 Kings (2 Kings 14:25). There we learn that Jonah is from Gath-Hepher (in Zebulan) and that he was likely a contemporary of Jeroboam II (782-753 BC). Therefore, Jonah might fit into the period between the reigns of Adad-Nirari II (810-783 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser II (745 BC). So, we might date the book somewhere between 800 and 750 BC. The story of Jonah shows the reluctance of a prophet to spread God’s mercy on the evil Assyrians living in Nineveh. It shows the incredible mercy of God on the most unlikely of people.

Micah

Micah’s name means “Who is like Yahweh?” He was born in Judah (the Southern Kingdom) about 20 miles west of Jerusalem (in Gath). This is why he only spends one chapter writing about the Northern Kingdom (ch. 6).This prophet brought a formal, legal case against Israel, warning them about God’s judgment. Micah lived contemporaneously with Isaiah, and this is why Micah 4:1-3 and Isaiah 2:2-4 are identical. In fact, Micah grew up close to Isaiah (did they know each other as kids?). Micah grew up in Moresheth-Gath (1:14) in Shepelah of Judah. This is right in the middle of the frontier-zone between Judah and Philistia. It may have been a rough area in which to grow up, and it would have made him starkly aware of Israel’s enemies.

Micah’s name means “Who is like Yahweh?” He was born in Judah (the Southern Kingdom) about 20 miles west of Jerusalem (in Gath). This is why he only spends one chapter writing about the Northern Kingdom (ch. 6).This prophet brought a formal, legal case against Israel, warning them about God’s judgment. Micah lived contemporaneously with Isaiah, and this is why Micah 4:1-3 and Isaiah 2:2-4 are identical. In fact, Micah grew up close to Isaiah (did they know each other as kids?). Micah grew up in Moresheth-Gath (1:14) in Shepelah of Judah. This is right in the middle of the frontier-zone between Judah and Philistia. It may have been a rough area in which to grow up, and it would have made him starkly aware of Israel’s enemies.

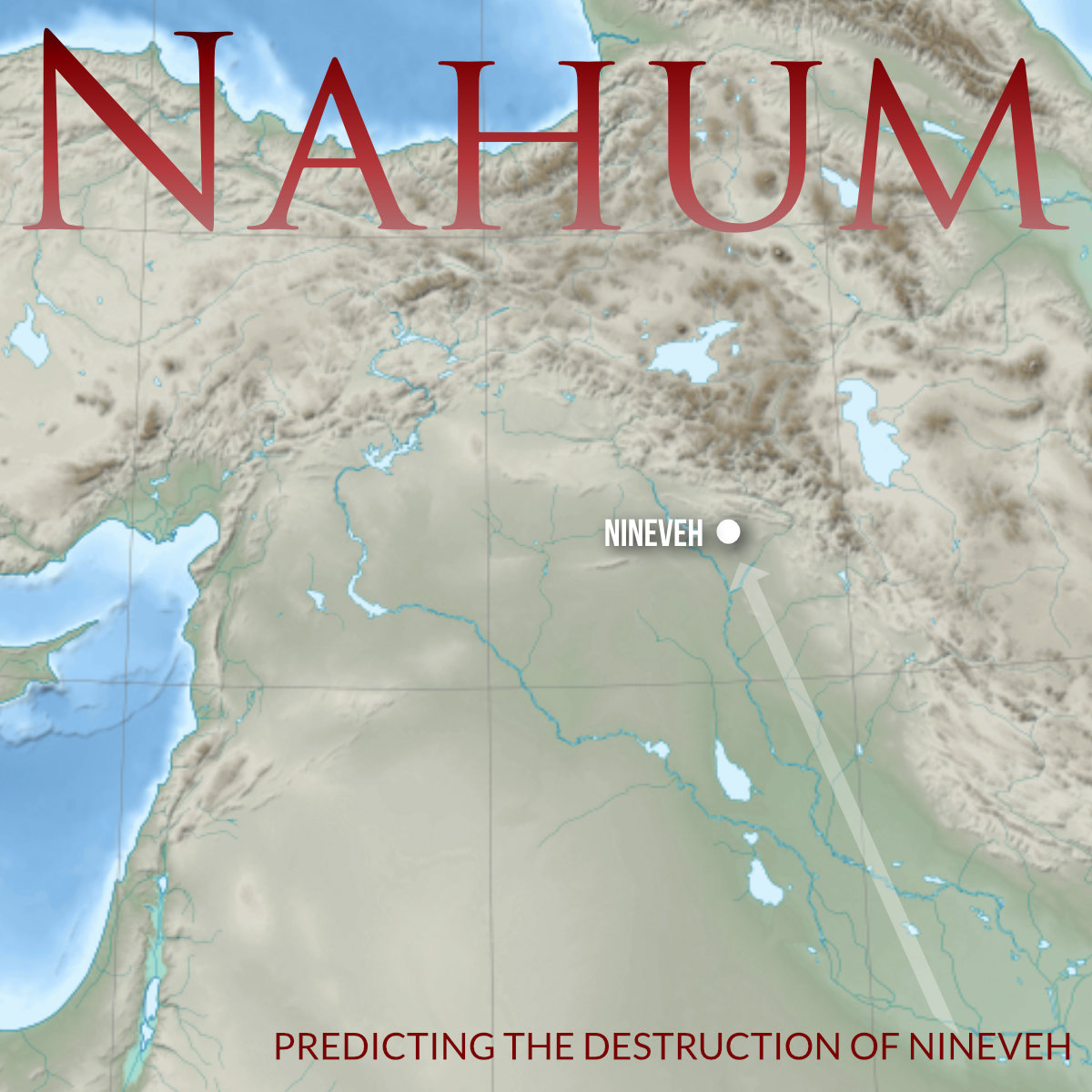

Nahum

Nahum’s name means “compassionate” or “consolation.” This is one of the great ironies of this book, because it describes God’s judgment over the Assyrians. God is compassionate through his judgment, however, because he is showing compassion on weak people who were harmed by the Assyrians—namely, Israel. Nahum wrote the book sometime between 663 and 612 BC. The historical background for the book is the occupation and oppression of Israel by the Assyrians. The Assyrians had invaded in 722 BC, and they were a vicious and sadistic nation. God used the Assyrians to judged Israel, but now God speaks about the judgment for Assyria.

Nahum’s name means “compassionate” or “consolation.” This is one of the great ironies of this book, because it describes God’s judgment over the Assyrians. God is compassionate through his judgment, however, because he is showing compassion on weak people who were harmed by the Assyrians—namely, Israel. Nahum wrote the book sometime between 663 and 612 BC. The historical background for the book is the occupation and oppression of Israel by the Assyrians. The Assyrians had invaded in 722 BC, and they were a vicious and sadistic nation. God used the Assyrians to judged Israel, but now God speaks about the judgment for Assyria.

Habakkuk

The name Habakkuk (Ḥabaqquq) might come from the root word “embrace” (ḥabaq). We know nothing about Habakkuk beyond what we have here in his book. The book doesn’t offer a date for itself, so we need to rely on internal evidence to surmise a date. Since the Chaldeans are well-known (Hab. 1:6-10), this likely places Habakkuk’s ministry before 605 BC, when the Babylonians made their first deportation of the people of Judah. Moreover, the book implies that the Assyrians had already fallen at the battle of Nineveh in 612 BC (Hab. 1:12-17; 2:6-20). Habakkuk focuses on the problem of God’s judgment for Israel. He wrestles through the fact that God is judging the nation, while other nations (seemingly more sinful) are going unpunished. How can this be the work of a loving God? Habakkuk choses to wait on God (Hab. 2:1).

The name Habakkuk (Ḥabaqquq) might come from the root word “embrace” (ḥabaq). We know nothing about Habakkuk beyond what we have here in his book. The book doesn’t offer a date for itself, so we need to rely on internal evidence to surmise a date. Since the Chaldeans are well-known (Hab. 1:6-10), this likely places Habakkuk’s ministry before 605 BC, when the Babylonians made their first deportation of the people of Judah. Moreover, the book implies that the Assyrians had already fallen at the battle of Nineveh in 612 BC (Hab. 1:12-17; 2:6-20). Habakkuk focuses on the problem of God’s judgment for Israel. He wrestles through the fact that God is judging the nation, while other nations (seemingly more sinful) are going unpunished. How can this be the work of a loving God? Habakkuk choses to wait on God (Hab. 2:1).

Zephaniah

Zephaniah’s name likely means “Yahweh has hidden him.” This book is dated to the reign of Josiah (640-622 BC). He probably worked with the young Josiah during his ministry, and he is a possible descendant of the King Hezekiah. He was writing specifically to Judah and Jerusalem before its destruction (1:4), urging them to repent. He is claiming that Judah has become God’s enemy! He urges them to repent, and also predicts a time of hope for the faithful remnant (3:9-20).

Zephaniah’s name likely means “Yahweh has hidden him.” This book is dated to the reign of Josiah (640-622 BC). He probably worked with the young Josiah during his ministry, and he is a possible descendant of the King Hezekiah. He was writing specifically to Judah and Jerusalem before its destruction (1:4), urging them to repent. He is claiming that Judah has become God’s enemy! He urges them to repent, and also predicts a time of hope for the faithful remnant (3:9-20).

Haggai

Haggai’s name means “festival” or “holiday.” He wrote this in 520 BC (the second year of Darius). His four messages spanning four months and 24 days. Haggai was likely one of the people who had seen the first temple (Hag. 2:3), and he was a contemporary of Zechariah (Ezra 5:2). The work on Temple stopped for 15 years, and this was the point that Haggai came in to speak for God in Israel (520 BC). This, no doubt, encouraged the people to continue their work (1:12).

Haggai’s name means “festival” or “holiday.” He wrote this in 520 BC (the second year of Darius). His four messages spanning four months and 24 days. Haggai was likely one of the people who had seen the first temple (Hag. 2:3), and he was a contemporary of Zechariah (Ezra 5:2). The work on Temple stopped for 15 years, and this was the point that Haggai came in to speak for God in Israel (520 BC). This, no doubt, encouraged the people to continue their work (1:12).

Zechariah

Zechariah’s name means “Yahweh has remembered.” The main message of Zechariah is the fact that God will spare Israel, while the evil nations will be destroyed. He is the son of Berechiah and grandson of Iddo (1:1). He is a younger prophet (2:4). Nehemiah mentions that he was friends with Zerubbabel at the presence of the Temple’s rebuilding (Neh. 12:4). He was also a colleague of Haggai during the rebuilding of the temple (Ezra 5:1; Zech. 1:12). He was martyred by a mob (Mt. 23:35; 2 Chron. 24:20-21), because of criticizing the immorality of the people. Zechariah most likely wrote his prophecy in the late 6th or early 5th century (October or November of 520 BC for chapters 1-8 and 480-470 BC for chapters 9-14). He predicts the Grecian Empire (9:13).

Zechariah’s name means “Yahweh has remembered.” The main message of Zechariah is the fact that God will spare Israel, while the evil nations will be destroyed. He is the son of Berechiah and grandson of Iddo (1:1). He is a younger prophet (2:4). Nehemiah mentions that he was friends with Zerubbabel at the presence of the Temple’s rebuilding (Neh. 12:4). He was also a colleague of Haggai during the rebuilding of the temple (Ezra 5:1; Zech. 1:12). He was martyred by a mob (Mt. 23:35; 2 Chron. 24:20-21), because of criticizing the immorality of the people. Zechariah most likely wrote his prophecy in the late 6th or early 5th century (October or November of 520 BC for chapters 1-8 and 480-470 BC for chapters 9-14). He predicts the Grecian Empire (9:13).

Malachi

Malachi is the final book of the OT—likely written around 435 BC. As it was written, Israel had returned from Exile, and they are now back. They had reformed the nation of idolatry, but as Malachi writes, the nation has turned into faulty, formalistic worship of God. Malachi’s main message was that the people needed to be faithful and authentic in their love for God. It ends with a hopeful anticipation of the Messiah coming to Earth.

Malachi is the final book of the OT—likely written around 435 BC. As it was written, Israel had returned from Exile, and they are now back. They had reformed the nation of idolatry, but as Malachi writes, the nation has turned into faulty, formalistic worship of God. Malachi’s main message was that the people needed to be faithful and authentic in their love for God. It ends with a hopeful anticipation of the Messiah coming to Earth.

Bible Difficulties for the Old Testament

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

1 & 2 Samuel, Kings, Chronicles

Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs

Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel

Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi

Additional Resources

Hebrew Study. Admittedly, we are not strong in our understanding of biblical Hebrew, and we mainly rely on commentators to aid us in this regard. That being said, the best Hebrew lexicon is HALOT (Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament). For free online resources, see www.blueletterbible.org, www.preceptaustin.org, or lumina.bible.org.

Bible Difficulties

We have written over 1,000 articles on Bible difficulties on this site.

Geisler, Norman L., and Thomas A. Howe. The Big Book of Bible Difficulties. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2008.

We find Geisler’s book on Bible difficulties to be the best on the market. It isn’t the most in-depth, but it is the most readable and cuts to the chase pretty quickly.

Archer, Gleason L. Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Pub. House, 1982.

Kaiser, Walter C. Hard Sayings of the OT. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1988.

J.P. Holding’s website (Tekton Apologetics Ministry)

Holding is an internet apologist who has a wealth of answers to Bible difficulties. We disagree with him on Preterism, Young Earth Creationism, and his views on genre criticism. But his website is extensive on Bible difficulties, and he has good material to consult and consider.

Apologetics Press (Apologetics Press):

This site has an extensive resource of Bible difficulties. We disagree with Apologetics Press on baptismal regeneration and Young Earth Creationism, but their site is an excellent resource for answers to Bible difficulties.

OT Survey Materials

Archer, Gleason L. A Survey of OT Introduction. Chicago: Moody, 1998.

Archer’s survey is a tour de force against critical scholarship. His rebuttal of the JEDP theory is excellent. The first 12 chapters are great reading for understanding higher and lower criticism. Each chapter afterward addresses the common criticisms of authorship, dating, and Bible difficulties in each book.

Merrill, Eugene H., Mark F. Rooker, and Michael A. Grisanti. The World and the Word: An Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2011.

Harrison, R. K. Introduction to the Old Testament. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2004.

Waltke, Bruce K., and Charles Yu. An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007.

OT Survey Audio

My friend Jim Leffel has a free class on OT Survey which I found very helpful in putting this study together (Found here).

Xenos Christian Fellowship OT teachings (found here).

Pastor Joe Focht OT teachings (found here).

Pastor Skip Heitzig teachings (found here).

Dr. Douglas Stuart has a free class on OT Survey here. We found Stuart to be an excellent scholar and lecturer. His audio is definitely worth listening to.

OT Survey Video

When starting a less understood book, we have benefited from watching The Bible Project videos, which give animated introductions and explanations of each book of the Bible.

[1] Spurgeon said, “The fact is that the whole system of truth is neither here nor there. Be it ours to know what is scriptural in all systems, and accept it.” Richard Ellisworth Day, The Shadow of the Brim (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1934), 144. Cited in Jerry Harmon, “The Soteriology of Charles Haddon Spurgeon and How it Impacted his Evangelism,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society (Spring 2006), p.56.