Authorship

Authorship

Amos’ name most likely means “burden-bearer.” He lived in Tekoa (Amos 1:1), which was a city ten miles south of Jerusalem. The city rested on the Judean range where Amos was a herdsman by trade (Amos 1:1; 7:14). Since his father is never mentioned, he could’ve come from humble backgrounds. Even though he was never formally trained as a prophet, he responded to God’s call to go speak to his people. Amos himself said, “I am not a prophet, nor am I the son of a prophet; for I am a herdsman and a grower of sycamore figs. 15 But the LORD took me from following the flock and the LORD said to me, ‘Go prophesy to My people Israel (Amos 7:14-15).

Critics do not often challenge the authenticity of Amos. Gleason Archer writes that “critics concede the authenticity of nearly all the text of Amos.”[1] Only a handful of verses have been questioned as later insertions, but this is based on the assumption that Israel’s history was compiled in the Documentary Hypothesis, which has been discredited (see “Authorship of the Pentateuch”). McComiskey concurs stating that “almost all scholars agree that the prophecy of Amos is, at least in essence, an authentic production of the man whose name it bears.”[2] He states that this is due to the type of language, vocabulary, and style that fits with an 8th century date.

Date

Archer writes that there “is general agreement among Old Testament scholars that Amos’ ministry is to be dated between 760 and 757 BC, toward the latter part of the reign of Jeroboam II (793–753).”[3] McComiskey concurs, dating this book sometime before 760 BC.[4]

Central mission

Amos spoke against the wealth and opulence of the people in his day (e.g. Amos 6:4). Thomas McComiskey writes, “Archaeology has illuminated this period through a number of discoveries. Excavations at Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom, have yielded hundreds of ivory inlays attesting to Amos’s description of the luxury enjoyed by these people.”[5]

Strategy of Amos

In the book of Amos, God is depicted as a “lion” (1:2), circling His prey and judging everyone around Israel. Amos draws in his audience by getting the people to agree with God’s judgment against everyone else. He has the people agreeing with him, because the enemies of Israel are so evil.

But then he turns the tables on his readers and says, “If God is truly just… what about YOUR evil practices?!” Then he preaches judgment on the people of Israel. He explains that God is going to judge them, and nothing can protect them besides repentance to God’s moral will. By the end of the book, the Temple is destroyed and all hope is lost… But then Amos predicts a time when the Temple and people will be restored.

Commentary on Amos

Unless otherwise stated, all citations are taken from the New American Standard Bible (NASB).

Amos 1 (Judgment against the nations)

(1:1) The “words of Amos” refers to his collected prophetic oracles (cf. Jer. 1:1; Prov. 30:1; Eccl. 1:1).

The term “envisioned” (ḥāzāh) has a “distinctive meaning and includes the idea of mental apprehension as well as visual observation.”[6]

Uzziah reigned from 790–740 BC, and Jeroboam II reigned from 793–753 BC.[7]

(1:2) God’s “roar” and “voice” have effects on the land—even drying up Mount Carmel. Roaring could involve judgment (Jer. 25:30-31), which is most likely here. Though, sometimes it involves God’s protection (Hos. 11:10-11).

Judgment against the nations

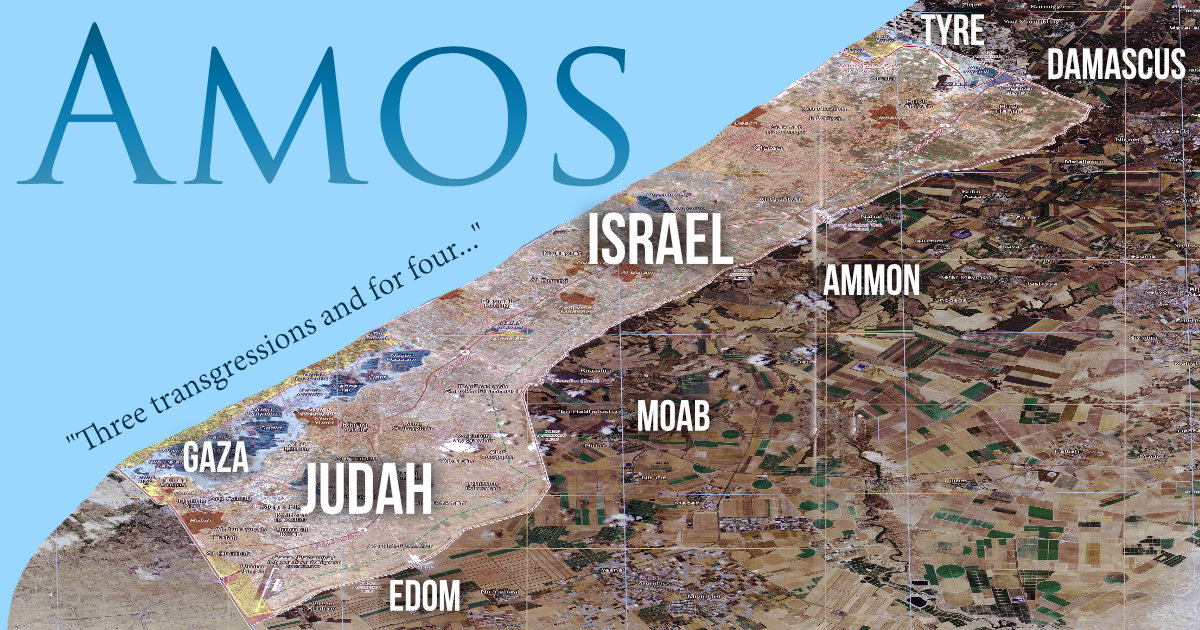

In this section (1:3-2:5), Amos begins by judging all of the nations for their sin. However, he judges each nation around Israel “in ever-tightening circles from one country to another, till at last he pounce[s] on Israel.”[8] In other words, the Israelites would applaud Amos’ judgment of the other nations, but one by one, Amos’ message of judgment gets closer and closer to home. Finally, Amos brings God’s judgment against Israel itself.

Damascus (Syria)

(1:3) Damascus represented the entire nation of Syria (i.e. Aram).

The expressions “three… and for four” is a literary motif. Sometimes it is used to refer to a definite number (Job 5:19; 33:29; Prov. 6:16; 30:15–31; Eccl. 11:2), while here it is being used to describe an indefinite number (Mic. 5:5–6). In other words, the prophet is accelerating the judgment as he speaks (“Three… No, four!”).

The “threshing” refers to “iron threshing sledges,” which were agricultural tools “made of parallel boards fitted with sharp points of iron or stone.”[9] This most likely occurred in 2 Kings 13:1-9.

(1:4) Hazael ruled Syria from 841-806 BC. Ben-Hadad was a common name. It could refer to two or three different people. McComiskey thinks that this refers to the ruler mentioned in 2 Kings 13:3.

“Fire” is mentioned in almost all of the oracles. It is most likely symbolic of judgment—not literal fire.[10]

(1:5) By breaking the “gate” of the city, this implies that the enemies had gained entrance to the city.

We have not identified the “Valley of Aven.”[11] However, like Hosea’s mention of “Beth Aven” (“house of wickedness”), rather than “Bethel” (“house of God”), this could be a pejorative description. “Beth-eden” and “Kir” (cf. Amos 9:7) are also difficult to identify.

Gaza (Philistines)

(1:6-8) The Philistines lived in a “pentapolis” of five cities—each of which was ruled by a different king: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, Gaza (Josh. 13:3; 1 Sam. 6:16–17). Amos mentions all five cites—except Gath. Gath had probably never recovered after Uzziah’s attack (2 Chron. 26:6) or perhaps Hazael’s attack (2 Kin. 12:17).

The main sin of the Philistines was slavery (v.6). Entire Edomite people groups were deported and sold as slaves. God’s judgment would be total annihilation.

Tyre

(1:9-10) The people of Tyre were judged for slavery. The “covenant” that Tyre broke might refer to the covenant between Hiram and Solomon (1 Kin. 5:12; 9:13), though we are not sure.

Edom

(1:11) “He pursued his brother with the sword” refers to the Edomites (descendants of Esau) attacking the Israelites (descendants of Jacob). Of course, Esau and Jacob were brothers. Thus, the Edomites and Israelites were often called “brothers” (Num. 20:14; Obad. 12; Deut. 23:7).

(1:12) Teman and Bozrah were cities in Edom. Teman was one of the largest cites, and Bozrah was a fortress city.[12]

Ammon

(1:13) The gruesome killing of the pregnant women probably occurred under Hazael’s leadership (2 Kin. 8:12). This was so graphic and unconscionable that Amos’ listeners must have screamed with horror and moral outrage.

(1:14) Rabbah was the capital of Ammon.

(1:15) The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Rabbah.

Amos 2 (Judgment against Israel)

This is an artificial chapter break. Amos is still drawing in his audience to be morally outraged at the “pagan nations” and their sinfulness. Little do they know, Amos is setting up a shocking argument that Israel deserves judgment.

Moab

(2:1) The “burning of the bones… to lime” refers to desecrating the corpse (2 Kin. 23:20; 1 Kin. 13:2; Ezek. 24:10; Amos 6:9–10).[13]

(2:2-3) Kerioth was a major city in Moab (Jer. 48:24). Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Moab (Josephus, Antiquities, 10.181-182).

Judah

(2:4-5) The people of Judah are judged based on the “law,” not just their moral conscience. The language of “lies” and “led astray” likely refers to idolatry.[14] God’s solution was judgment (v.5).

Israel!

Up until this point, the Israelites would have been cheering God’s judgment against the pagan nations and their northern enemy of Judah. Amos eliciting this moral indignation in the Israelites only to turn it on them! Here, Amos tells the Israelites that God is going to judge them as well.

(2:6) The Israelites were guilty of human trafficking. Only they would sell an innocent human being for a “pair of sandals” (!!).

(2:7) “Craving the dust” could refer to the rich enjoying how the poor were mourning. In other words, they enjoyed watching the poor suffer without any regret.

The “man” and “father” having the same girl refers to sexual immorality of some kind. It could refer to ritual prostitution (notice “every altar” in verse 8) or some form of incestuous relationship.[15]

(2:8) At this time, the “garments taken as pledges” referred to giving your expensive clothing as collateral in a business deal. They give these pledges to idols (“every altar… house of their god”).

(2:9) God empowered them to take over this land from the wicked Amorites (Gen. 15:16). However, the Israelites had now become just as bad as the Amorites.

(2:10) God has rescued the Israelites from slavery—only to see them fall into the slavery of idolatry.

(2:11-12) God raised up spiritual men to lead the people during this time, so that they wouldn’t be without direction and leadership (v.11). But the people gagged the prophets and made the Nazirites drink wine. This is not merely ignoring God’s leadership, but rebelling directly against it. For an explanation of the Nazarites, see comments on Numbers 6:1-21.

(2:13) McComiskey understands this to be referring to the nation being crushed under a heavy lead.[16] The NASB obscures this understanding, but the NIV captures it well.

(2:14-16) It wouldn’t matter how fast, strong, or mighty the Israelites were. God had turned against them, and they were going to fall. In the Exodus and Conquest, God had fought for the Israelites (vv.9-12), but now, he was fighting against them.

Amos 3 (God will judge Israel)

(3:1) Even though God had rescued the nation in the past, the current generation needed to commit to God in order to experience God’s blessings.

(3:2) The word “chosen” (yāḏaʿ) is typically translated “known.” However, God’s election didn’t result in blessing, but cursing. Because the Israelites had more special revelation, they were held to a higher standard.

(3:3-5) The answer to all of these rhetorical questions is No.

Amos gives a bunch of illustrations for animals that wouldn’t make any sense (e.g. a lion growling over no prey, a bird falling into a trap that doesn’t have bait, etc.). Then he ties this in with God’s plan. He is not capricious. If something happens, he is in control of it (vv.6-7). This becomes important when we realize that God is going to judge the people of Israel.

(3:6) Older translations like the KJV translated “calamity” (rāʿāh) as “evil.” McComiskey writes, “The word has that meaning in Hebrew, but the emphasis in this context on the city warrants only the meaning ‘disaster.’”[17] For more on this, see comments on Isaiah 45:7.

(3:7) God wants to reveal his will to his people (Ps. 25:14; Prov. 3:32).

(3:8) No one can stop God’s word from going out. People “tremble” at his word like they would at the “roar” of a “lion.”

(3:9) Amos wants the Philistines and Egyptians to witness the bloodshed.

(3:10) This refers to the Israelites. These people store up evil in their fortresses.

(3:11) Assyria was the “enemy” to loot Israel.

(3:12) Shepherds had to produce remains to show that they did everything they could to protect their sheep (Ex. 22:13). Similarly, the people of Israel will be either be (1) dead along with the rest of the nation when Assyria comes or (2) the faithful remnant will be plucked from the lion’s mouth. The difficulty of the second view is that the context is teaching judgment—not rescue.

(3:13) “Jacob” (rather than Israel) is specifically mentioned because this is the center hub of the country.

(3:14-15) Fugitives could find sanctuary by grabbing the horns of the altar (1 Kin. 1:50). But even this would not stop God’s judgment.

Amos 4 (Samaria)

Materialistic women in Samaria

(4:1) Amos compared the women of Samaria to cows of “Bashan,” which were well known as expensive cattle (Ezek. 39:18). In the metaphor, the women urge the men to oppress the poor to satisfy their thirst (or to become drunk).

(4:2-3) When God swears by his “holiness,” this means that this judgment will definitely come to pass. The people won’t have a choice in their judgment (“meat hooks… fish hooks”). The location of “Harmon” is unknown.[18]

(4:4-5) “Bethel” was the religious capital of the northern kingdom. It became the northern kingdom’s alternative to worshipping in Jerusalem. Even the king worshipped there (Amos 7:13). “Gilgal” was also a place of religious worship.

Tithing every three days could be an interpretation of Deuteronomy 14:28. McComiskey states that “years” (yāmîm) can also be rendered “days.” He writes that days may “be used to refer to the full cycle of days in a given period and thus mean a year (Exod 13:10; Judg 11:40; 1 Sam 1:3).”[19]

Why would God command the people to sin? This is clearly a sarcastic taunt on God’s behalf. The people are so settled on worshipping him the wrong way that God sarcastically tells them to do this. Note, however, that this is because this is what the people “love to do” (v.5). In other words, the people already wanted to sin and had been sinning from the start.

God’s discipline on the people

This section shows how God was disciplining the people from multiple different angles. However, the people wouldn’t turn to God. Amos states, “You have not returned to Me” five times in this section. The people had become hardened.

(4:6) “Cleanness of teeth” is an idiom for “no food,” as the second strophe shows (“lack of bread”). God wanted the people to see their need for him and return to him.

(4:7-8) God controlled the amount and location of the rain fall, but the people didn’t return to God.

(4:9-10) God judged their crops (v.9) and their people (v.10). But the people didn’t turn to God.

(4:11) God brought judgment similar to Sodom and Gomorrah. This likely refers to judgment in general—namely, the Assyrians. Even though God protected them, they didn’t turn to him.

Conclusion

(4:12) In context, the expression “prepare to meet your God” is not a positive encounter. The people would meet God in judgment—not relationship. It might be similar to a sword fighter saying, “Prepare to die!”

(4:13) “His thoughts” is from a root word (śēḥó) that is never used of God’s thoughts. In context, this refers most likely to God knowing the thoughts of humans, rather than revealing his own thoughts to humans (Amos 3:7).[20]

The verse ends emphasizing God’s transcendence and sovereignty as the Ruler of the world.

Amos 5 (Judgment for Israel)

(5:1) A “dirge” (qînāh) was a funeral lament. Amos writes this before the destruction of Israel, because the northern nation was already as good as dead.

(5:2) Amos pictures Israel as a “virgin” who dies without leaving behind offspring. The expression “she will not rise again” does not refer to being perpetually or eternally destroyed by God. Later, we read that God will continue to work through Israel (Amos 9:9-12).

(5:3) Only 10% of Israel’s soldiers will survive this battle.

(5:4) To “seek” (dāraš) God means “to turn to him in trust and confidence.”[21] Moreover, “live” (ḥāyāh) in this context refers to physical life during the destruction of the northern nation.

(5:5) It would be tempting for the people of Israel to flee to these cities and strongholds for protection. But Amos tells them that all of these will be ransacked.

(5:6) “House of Joseph” refers to Israel, because the largest tribe of the north was Ephraim (from Joseph’s line).[22]

(5:7) “Wormwood” (laʿanāh) was a bitter plant.

(5:8-9) Amos switches from God’s sovereignty and power over creation (v.8) to God’s sovereignty over nations (v.9).

(5:10) People would carry out court cases in the city “gate” (Deut. 21:19; Josh. 20:4; Ruth 4:1). The people who “reproved” people were those who were hated because they stood up for justice.

(5:11) The rich became richer by exploiting the poor. But Amos warns them that they will never enjoy their big beautiful homes and vineyards.

(5:12-13) The “prudent person” is “silent,” because he knows that everyone is corrupt. There is no use speaking up for justice when others would simply bring more persecution.

(5:14) The people couldn’t have mere outward religiosity. They needed inward change. The expression “Just as you have said!” means that they thought that God was already with them.[23] They were dead wrong.

(5:15) This intensifies the imperatives of verse 14. It wasn’t enough to “seek” goodness; they needed to learn to “love” it. (The same is inversely true with “evil”).

(5:16-17) The people would weep and mourn as God passed through in judgment.

The Day of the Lord

(5:18-20) The people thought that the “day of the Lord” would be a day of rescue—not wrath. However, Amos tells the people with various metaphors that they will be moving from the frying pan and into the fire.

God hates false worship

(5:21) Amos used the word “hate” (śānēʾ) to refer to how the Israelites should hate evil. Here, God “hates” their false worship!

(Amos 5:21-22) Do good works replace the Temple sacrifices?

(5:22-23) Amos specifies that God abhors the sacrifices and the songs. All of these were given with a pseudo spirituality.

(5:24) Dr. John Perkins named his autobiography after this verse, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. quoted this passage in his “I Have a Dream” speech. The language implies an overflow of justice—not just a little bit at a time.

(5:25) The answer to this question is No.[24] But what does this imply? It could mean that God didn’t need their sacrifices then, and he also doesn’t want them now (i.e. in Amos’ day). However, this would mean that the sacrificial system was worthless. A better understanding seems to be that the people in the Wilderness were idolaters all throughout their history—both then and now.

(5:26) The mention of “Sikkuth” and “Kiyyun” refer to “idolatrous worship of an unknown astral deity.”[25]

(5:27) Amos predicts that the people would be sent into Exile for their sins.

Amos 6 (Judgment for Jerusalem)

(6:1-2) The rich and affluent people were complacent in their nation, thinking that they were secure. God sarcastically asks them to go to these other cities and compare themselves. He asks, “Are you really that much better than these Pagan cities?”

(6:3) The people didn’t want to hear Amos’ message of judgment (“the day of calamity”).

(6:4-6) Amos describes the opulence of the people in detail.

(6:7) Because of the sin of affluence and avarice, they were going to be exiled from their land.

(6:8) The pride and “arrogance” of the people was something that God “loathed” and “detested.”

(6:9) This is a vivid illustration of the judgment being described thus far.

(6:10) When the nearest living relative comes to bury the dead, the people left will not want to hear God’s name spoken “for fear that the Lord will turn his wrath on him.”[26]

(6:11) This section (vv.9-10) shows that God’s judgment will apply to individual houses and even individual people.

(6:12-13) These questions are absurd questions that demand an answer of No. This shows that the attitude of the people was equally absurd.

“Lodebar” and “Karnaim” were “evidently the sites of recent victories in Jeroboam’s incursion into Aramean territory.”[27] However, Lodebar meant “no thing,” which showed that this victory was not impressive, and they were boasting in victories that weren’t impressive.

(6:14) This unnamed nation (Assyria) would conquer them from the northern border (Hamath) all the way to the southern border of Israel (Arabah).

Amos 7 (Three visions of judgment)

Vision #1. Locust swarm

(7:1) The king had first access to the crops. In the meantime, God judged the harvest through a locust swarm.

(7:2-3) God responded to Amos’ intercession. It seems that Amos was banking on God being merciful to such a “small” nation as Jacob.

(Amos 7:2-3) Did God change his mind? Isn’t God immutable?

Vision #2. Fire

(7:4-6) This was no ordinary fire. It was going to consume the land and sea (“deep”). Again, God listened to Amos’ intercession based on the weakness of Jacob.

Vision #3. Plumb line

(7:7-9) God is “standing” (niṣṣāḇ), which describes “firmness and determination.”[28] It foreshadows that God wouldn’t allow Amos to “change his mind” through a prayerful intercession.

A “plumb line” is a standard to test whether or not a wall is built well vertically. This vision showed that God’s judgment was not arbitrary, but based on an objective standard which the people failed.

Notice that Amos intercedes on the first two vision, but not the third.

(7:10-13) The priest (Amaziah) slandered Amos to the king (Jeroboam), accusing him of treason. Amos’ predictions of God’s judgment were used to imply that Amos was against King Jeroboam.

(7:14-15) Amos seems to be saying that he wasn’t a prophet by birth (v.14), but rather by calling (v.15).[29]

(7:16-17) Amos made a short term prediction about Amaziah and his family. Amaziah’s wife would be raped, his children killed, and Amaziah would die in Gentile lands.

Amos 8 (Vision of the summer fruit)

(8:1-2) The word “summer fruit” (qāyiṣ) is wordplay with the word “end” (qēṣ). The NIV captures this wordplay well.[30]

(8:3) The “silence” refers to the reverence that the people should have at seeing the corpses carried out.

(8:4-5) These businessmen couldn’t wait for the festivals to be over so that they could make a huge profit.

(8:6) These dishonest merchants would mix chaff in with the wheat to make it seem heavier.

(8:7-8) This could refer to the coming earthquake that would afflict the land (Amos 1:1).

(8:9) This darkness at noon shows that judgment is taking place. Is this a prophecy of the Cross (v.9)? It seems best to say that this was a symbol for God’s judgment, which also occurred at the Cross. God’s curse will be that the people won’t have God’s word.

(8:10) This judgment is compared metaphorically to weeping and mourning over the death of your only child.

(8:11-12) Because these people rejected God’s word, God had rejected them. They are pictured as metaphorically starving and thirsting for God’s word.

(8:13-14) People worshipped idols at Dan and Beersheba. This is why these places would be the locations of God’s judgment.

Amos 9 (The regathering of Israel)

Remember that the book opened with the chronological marker (“two years before the earthquake”). This must have been one heck of an earthquake, because Zechariah references it too (Zech. 14:2). The walls of Gath fell down at this time in the 8th century BC, which must have been an 8 point on the Richter scale. This final vision shows that God is shaking their Temple apart. The whole book has been pointing forward to this conclusion. They were trusting in their religious festivals (5:21-22), rather than God. So God takes these away from them.

But the book ends on a positive note: God will not totally destroy Israel (v.8). He will rebuild the Temple (v.11) and regather Israel (v.13).

(9:1-4) God isn’t in the Temple but beside the altar. God commanded judgment for all these people: none would escape.

(9:5-6) This gives poetic to describe the greatness and grandeur of God.

(9:7) The people of Ethiopia were obscure, and so, this would be insulting to the “elect” Israelites.[31]

(9:8-10) Even though this entire book has been about judgment, we are given a ray of hope. God will come back to save some of the people in a remnant.

(9:11) The fallen “booth” (sukkāh) refers to what is left of David’s dynasty.[32] Because of the Davidic Covenant, God would restore the Davidic line.

(Amos 9:11) Did James misquote this passage? Why did he quote it?

(9:12) James quotes this passage in the NT, but he doesn’t quote the MT: “Possess the remnant of Edom.” Instead, he quotes the LXX: “The rest of mankind may seek the Lord.” However, the thrust of the passage is not on the first part, but the second. The focus is on “the nations [Gentiles] who are called by My name.” This is James’ argument: the Gentiles will be included in God’s plan.[33]

(9:13) The “plowman” overtaking the “reaper” refers to a “great abundance of the produce of the field.”[34] In other words, they can’t collect the harvest quickly enough.

(9:14-15) None of the these predictions has occurred yet. So this must refer to the future. At this time, Israel will be a nation again. This is also a permanent regathering, because Amos writes, “They will not again be rooted out from their land.” In other words, once the nation is planted, they will never be dispersed again.

[1] Archer, Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction (3rd. ed.). Chicago: Moody Press. 1994. 353.

[2] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 270). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[3] Archer, Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction (3rd. ed.). Chicago: Moody Press. 1994. 353.

[4] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 275). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[5] McComiskey, Thomas. Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House. 1986. 270.

[6] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 279). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[7] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 280). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[8] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 281). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[9] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 283). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[10] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 283). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[11] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 284). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[12] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 288). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[13] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 291). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[14] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 292). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[15] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 294). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[16] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 295). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[17] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 299). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[18] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 303). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[19] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 305). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[20] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 308). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[21] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 311). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[22] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 312). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[23] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 313). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[24] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 316). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[25] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 317). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[26] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 319). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[27] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 320). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[28] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 321). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[29] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 323). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[30] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 325). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[31] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 327). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[32] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 329). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[33] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 330). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

[34] McComiskey, T. E. (1986). Amos. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Daniel and the Minor Prophets (Vol. 7, p. 331). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.