Unless otherwise stated, all citations are taken from the New American Standard Bible (NASB).

This account depicts what human autonomy can accomplish if God is not in the picture. Waltke[1] understands this to be a “flashback” that explains how the nations were separated (Gen. 10:25).

Humans were supposed to “fill the earth,” but instead, they gather together in one place.

(Gen. 11:1-9) Did ancient humans really build the Tower of Babel?

(11:1) Now the whole earth used the same language and the same words.

“The whole earth.” This expression can be used for a distinct region (Gen. 13:9, 15; 41:41, 43, 54; 45:20; Ex. 9:9; 10:14; Deut. 11:25; 19:8; 34:1; 1 Sam 30:16) or for the entire globe (Gen. 1:29; 19:31; Ex. 19:5; Num. 14:21). Therefore, it’s possible that the “land” of this great empire is in view (v.2), not the entire globe. Sailhamer takes the view that the “whole earth” is actually “limited here to a particular geographical location since in the following verse it says that the “men moved eastward” and found the valley where they built the city of Babylon.” Therefore, the focus is on “the founding of the city of Babylon at the end of a migration of people from the west.”[2]

“Used the same language.” In chapter 10, we read about multiple languages. It’s possible that chapter 10 is not placed in chronological order with chapter 11. However, Hamilton[3] thinks that this could refer to a lingua franca that all of these peoples used in addition to their local languages.

(11:2) It came about as they journeyed east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there.

Shinar is the Mesopotamian region of Babylonia.[4]

God commanded them to “fill the earth” (Gen. 9:1), but they rejected this command. They chose to “settle” in one location.

The desire to journey “east” might show a parallel with being exiled to east of Eden: “The language ‘east(ward)’ marks events of separation in Genesis.”[5] Consequently, we discover a theme in Genesis when humans travel to the east: “In the Genesis narratives, when man goes ‘east,’ he leaves the land of blessing (Eden and the Promised Land) and goes to a land where the greatest of his hopes will turn to ruin (Babylon and Sodom).”[6] We see this with the first humans (Gen. 3:24), Cain (Gen. 4:16), Lot (Gen. 13:10-12), Abraham’s other sons (Gen. 25:6), and Jacob (Gen. 29:1).

(11:3) They said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks and burn them thoroughly.” And they used brick for stone, and they used tar for mortar.

They begin building and manufacturing bricks to create fortresses for themselves. Production of bricks was common in this area, and it dates very early in history. Mathews writes, “Production of brickware for construction was a common feature in early Mesopotamia. Its technology was invented in Babylonia during the fourth millennium and later exported to other countries.”[7]

(11:4) They said, “Come, let us build for ourselves a city, and a tower whose top will reach into heaven, and let us make for ourselves a name, otherwise we will be scattered abroad over the face of the whole earth.”

(11:5) The LORD came down to see the city and the tower which the sons of men had built.

In Mesopotamia, they didn’t build towers for defensive purposes (like they did in Canaan). Instead, this was a “ziggurat” (which comes from Akkadian, zaqāru “to build high”[8]). The purpose was to give “humanity access to heaven” and to serve as a “convenient stairway for the gods to come down into their temple and into the city.”[9] It was “conceived as a stairway that would give them access to the realm of the divine.”[10]

When Jacob saw a vision of a ladder to heaven, he said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven” (Gen. 28:17). Waltke writes, “The ziggurat culminated in a small shrine at the top, often painted with blue enamel to make it blend with the celestial home of the gods. Here the addition ‘to the heavens’ shows they are vying with God himself. The Lord, not humankind, dwells in the heavens.”[11]

These humans were trying to reach God, but God needed to “come down” to see their puny efforts. Wenham observes, “With heavy irony we now see the tower through God’s eyes. This tower which man thought reached to heaven, God can hardly see! From the height of heaven it seems insignificant, so the Lord must come down to look at it!”[12] Waltke concurs, “Its builders think their temple tower reaches into heaven; it is so low that the Lord has to descend from heaven just to see it!”[13] This “shows the escapade for what it was—a tiny tower, conceived by a puny plan and attempted by a pint-sized people.”[14] Isaiah writes, “It is He who sits above the circle of the earth, and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers” (Isa. 40:22).

“Let us make for ourselves a name.” They wanted to make a “name” (šēm) for themselves. Earlier, Moses used the same term to refer to the “men of renown” (Gen. 6:4).

What is at the heart of what they were doing? The people wanted to create an identity for themselves, rather than receive one from God. The people slaved over this self-made identity project. They built this ziggurat with their blood, sweat, and tears, and they slaved over this for who knows how long.

God never intended humans to receive their identity this way. In the very next chapter, God will freely give a “name” and identity to Abraham: “I will make your name great” (Gen. 12:2). No works, no slavery. None of that. God wants humans to experience an identity that really matters. An identity that comes from him alone.

(11:6) The LORD said, “Behold, they are one people, and they all have the same language. And this is what they began to do, and now nothing which they purpose to do will be impossible for them.

This sounds like hyperbole. Yet the point is true. If humans were totally unified, they could accomplish so much! But the problem with progress is this: Just because we can do something doesn’t mean that we should do something. Without God, humanity blurs the lines between these two crucial issues.

(11:7) “Come, let Us go down and there confuse their language, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.”

“Confuse” (bālal) is a pun with the name “Babel.”

God intervenes to disrupt their language, slowing down their unified progress. At the end of history, humans work their way back together to form a one-world government. This entire time humanity has been trying to get back to Babel, standing in defiance of God.

At Pentecost (Acts 2), God brought people together through the Cross. God isn’t against unification. Instead, he knows that unification without Christ will result in evil—not good. So, after the Cross, God united human language to bring the different people’s together at Pentecost. Now, the Church can all have the same language to unite us. And now, under God’s leadership, “now nothing which they purpose to do will be impossible for them” (Gen. 11:6).

Why does God stop them by confusing their language? Hamilton[15] notes that this is the key issue. If God destroyed the tower, they would’ve simply rebuilt it.

(11:8) So the LORD scattered them abroad from there over the face of the whole earth; and they stopped building the city.

The people were afraid that they would be “scattered abroad over the face of the whole earth” (Gen. 11:4). In the end, the great fear of the people was realized anyhow. Building an identity apart from God is doomed to failure. The entire project was “confused” from start to finish. That’s why it is called “Babel.”

(11:9) Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the LORD confused the language of the whole earth; and from there the LORD scattered them abroad over the face of the whole earth.

“Babel” is a play on words. Waltke writes, “The narrator parodies Akkadian bāḇ-ilu, meaning ‘gate of god,’ with its Hebrew phonological equivalent bāḇel, meaning ‘confusion.’ Babel likely refers to the city of Babylon (cf. 10:10, with the same Hebrew word). The mention of Shinar (10:10; 11:2) and Babel/Babylon connects this city and its tower with Nimrod’s antigod kingdom. Nimrod built cities that replicated the original Babel and its ziggurat.”[16]

The crumbling of this massive building project must’ve seemed like an abject failure and crushing embarrassment to the people. Yet, from God’s perspective, this was a great act of mercy: If humans succeeded in their plans, it would’ve ended in misery. Wenham writes, “The tower of Babel was intended to be a monument to human effort: instead it became a reminder of divine judgment on human pride and folly.”[17]

Questions for Reflection

God destroyed humanity with the Flood in chapter 6. Here, however, God takes a softer approach with the people of Babel. Why do you think God takes a gentler approach in this section—when the people try to make an identity for themselves?

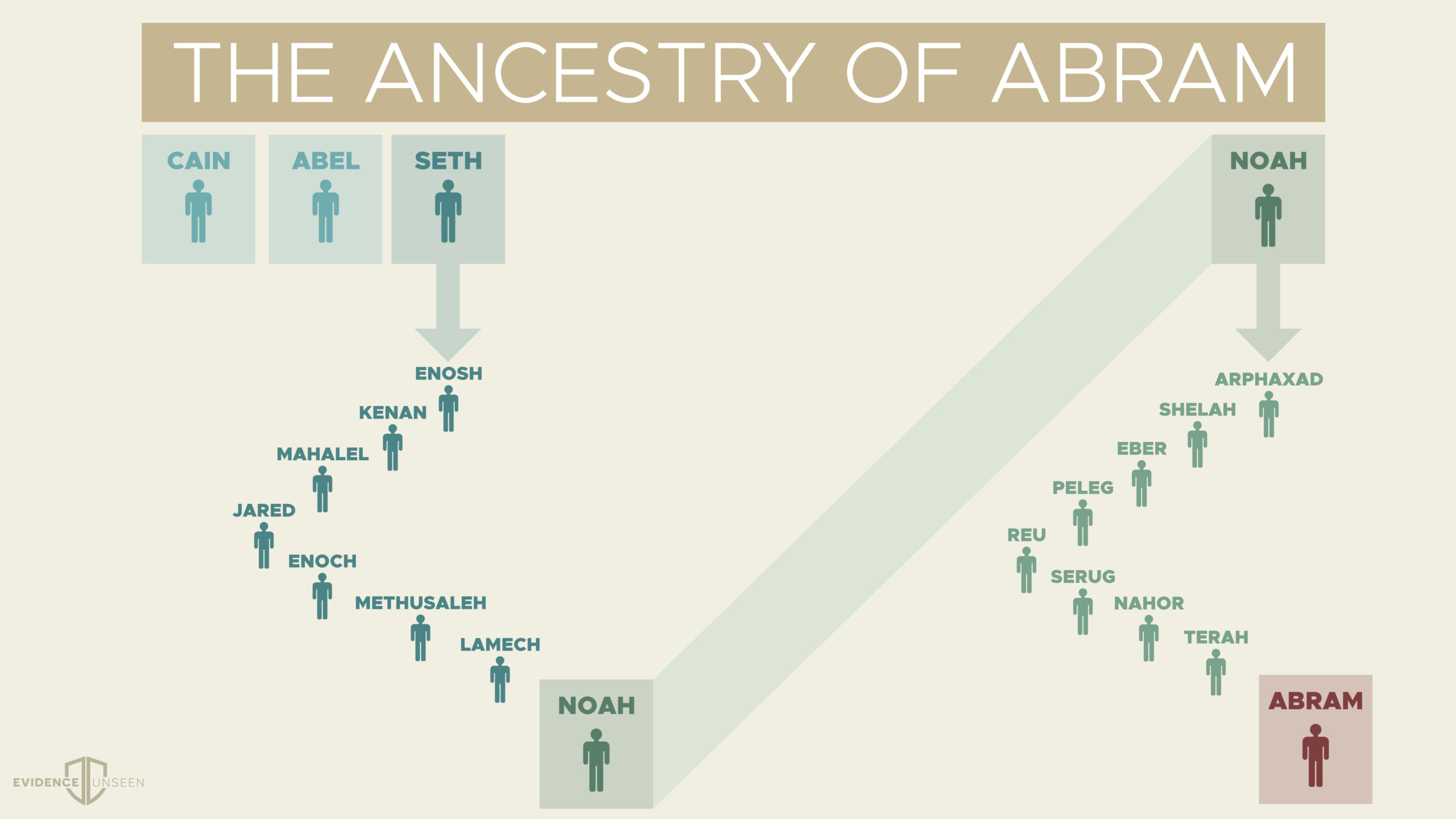

Genealogy from Noah to Abraham

This genealogy stands in stark contrast to the events at the Tower of Babel. The people wanted to build a “name” (šēm) for themselves at Babel, but God gives a name to Abraham through the person of “Shem” (šem). Waltke writes, “Ironically, the tower builders were seeking to ‘make a name’ but have no names, and the city they built receives the shameful name ‘Confusion.’ God gives the elect of Shem an everlasting name in this genealogy, and above all, he will exalt the name of the faithful descendant Abraham (see 12:2).”[18] Instead of focusing on the repeated refrain “and he died…” (cf. Gen. 5), we see the refrain “and he had other sons and daughters…”

(11:10-27) These are the records of the generations of Shem. Shem was one hundred years old, and became the father of Arpachshad two years after the flood; 11 and Shem lived five hundred years after he became the father of Arpachshad, and he had other sons and daughters. 12 Arpachshad lived thirty-five years, and became the father of Shelah; 13 and Arpachshad lived four hundred and three years after he became the father of Shelah, and he had other sons and daughters. 14 Shelah lived thirty years, and became the father of Eber; 15 and Shelah lived four hundred and three years after he became the father of Eber, and he had other sons and daughters. 16 Eber lived thirty-four years, and became the father of Peleg; 17 and Eber lived four hundred and thirty years after he became the father of Peleg, and he had other sons and daughters. 18 Peleg lived thirty years, and became the father of Reu; 19 and Peleg lived two hundred and nine years after he became the father of Reu, and he had other sons and daughters. 20 Reu lived thirty-two years, and became the father of Serug; 21 and Reu lived two hundred and seven years after he became the father of Serug, and he had other sons and daughters. 22 Serug lived thirty years, and became the father of Nahor; 23 and Serug lived two hundred years after he became the father of Nahor, and he had other sons and daughters. 24 Nahor lived twenty-nine years, and became the father of Terah; 25 and Nahor lived one hundred and nineteen years after he became the father of Terah, and he had other sons and daughters. 26 Terah lived seventy years, and became the father of Abram, Nahor and Haran. 27 Now these are the records of the generations of Terah. Terah became the father of Abram, Nahor and Haran; and Haran became the father of Lot.

The purpose of this genealogy is to connect Shem (the Semites) to Abraham (the Hebrews). One of Shem’s descendants was Eber, and “in his days the earth was divided” (Gen. 10:25). This refers to Eber’s two sons: Peleg and Joktan. Peleg leads to Abraham and the Israelites, while Joktan leads to the Babylonians. There is even a play on words with the name “Shem” (šēm) and the desire of Babel to make a “name” (šēm).[19]

In Genesis 5, the genealogy contained ten descendants (from Adam to Noah), and this genealogy in Genesis 11 contains ten descendants as well (from Shem to Abraham). This shows that God’s promise of the “seed” (Gen. 3:15) still continues: “Though the seed of Noah were scattered at Babylon, God has preserved a line of ten great men from Noah to the chosen seed of Abraham. Out of the ruins of two great cities, the city of Cain and the city of Babylon, God has preserved his promised seed.”[20]

This genealogy contains gaps: “If one regarded the Masoretic text as closed (i.e., without chronological gaps), the events of Genesis 9-11 would cover less than three centuries and all of Abraham’s ancestors would have been living when he was born. Shem would have outlived Abraham by thirty-five years, and Shem and Eber would have been contemporaries with Jacob!”[21] Likewise, Mathews writes, “As the numbers stand in the Hebrew text (MT), Abraham was born 292 years after the flood. This would mean that Noah and Abraham were contemporaries as were Shem and Eber with Jacob. Since Shem’s life span was 600 years, and his son Arphaxad was born at 100 years and Abraham was born 290 years after Arphaxad (= 390), given that Abraham died at 175 years (= 565), Shem’s life span would actually exceed the death of Abraham by thirty-five years.”[22]

Slowly, we see the lifespans of these people shortening until the time of Abraham who lived for 175 years.

(11:28-29) Haran died in the presence of his father Terah in the land of his birth, in Ur of the Chaldeans. 29 Abram and Nahor took wives for themselves. The name of Abram’s wife was Sarai; and the name of Nahor’s wife was Milcah, the daughter of Haran, the father of Milcah and Iscah.

What a strange family tree among these three brothers: Abram, Nahor, and Haran. Nahor married his dead brother’s daughter (Milcah). They were also polytheists: “Joshua 24:2 shows that Terah and his forbears ‘served other gods’; his own name and those of Laban, Sarah and Milcah point towards the moon-god as perhaps the most prominent of these. Certainly Ur and Haran were centres of moon worship, which may suggest why the migration halted where it did (31). Terah’s motive in leaving Ur may have been no more than prudence (the Elamites destroyed the city c. 1950 BC); but Abram had already heard the call of God (Acts 7:2-4).”[23] Recently, the association between Terah’s name (trḥ) being related to the word “moon” or “moon god” (yārēaḥ) has been rejected,[24] even though the it’s clear that he was an idolater.

(11:30-31) Sarai was barren; she had no child. 31 Terah took Abram his son, and Lot the son of Haran, his grandson, and Sarai his daughter-in-law, his son Abram’s wife; and they went out together from Ur of the Chaldeans in order to enter the land of Canaan; and they went as far as Haran, and settled there.

“Ur of the Chaldeans.” The land of the Chaldeans was Babylon (Isa. 13:19; Jer. 24:5; 25:12; 50:1, 8, 35, 45; 51:24, 54; Ezek. 1:3; 12:13; 23:15, 23). Later authors stress the fact that Abraham was called out of this land (Gen. 15:7; Neh. 9:7; Acts 7:2-3). Perhaps Abraham serves as a prototype of all believers who leave Babylon (the world-system?) to enter the Promised Land.

Families often stuck together in clans in the ancient Near East. It was a form of protection and community. Terah took Abram, Lot (Abram’s nephew), and Sarai (Abram’s wife). They wanted to get out of Ur of the Chaldeans and go to Canaan.

They made it as far as Haran. But this is a territory—not to be confused with Abram’s brother. This was a location “on the bank of the Balikh River, 550 miles (885 km) northwest of Ur and close to the present-day Syrian-Turkish border. Like Ur, it was an important center of moon worship.”[25] This family was right in the center of Paganism when God found them.

(11:32) The days of Terah were two hundred and five years; and Terah died in Haran.

Terah dies. Abram is now the patriarch of the family—with his nephew Lot and his wife Sarai.

Timeline for Abraham’s life

Abram was 10 years older than Sarai (Gen. 17:17).

Abram was 75 went he got his calling in Haran (Gen. 12:4).

Abram was 86 years old when Ishmael was born (Gen. 16:16).

Abram was 99 years old when God gave him circumcision (Gen. 17:1).

God called Abraham a prophet (Gen. 20:7).

Abraham was 100 years old and Sarah was 90 years old when Isaac was born (Gen. 21:5).

Sarah died at 127 years old (Gen. 23:1).

Abraham died at the age of 175 (Gen. 25:7).

[1] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 175.

[2] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 105.

[3] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 350-351.

[4] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 479.

[5] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 478.

[6] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 104.

[7] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 481.

[8] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.179.

[9] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 179.

[10] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 481.

[11] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.179.

[12] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 240.

[13] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 178.

[14] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 483.

[15] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 355.

[16] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.181.

[17] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 241-242.

[18] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 187.

[19] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 104.

[20] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 108.

[21] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 188.

[22] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 493-494.

[23] Derek Kidner, Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.120.

[24] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 499.

[25] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.201.