Unless otherwise stated, all citations are taken from the New American Standard Bible (NASB).

What is the purpose of the Table of Nations? Waltke[1] and Hamilton[2] both note that this table of nations is unique among ancient Near East literature. The purpose must be to show that God is not a provincial deity who only reigns over a local territory. Rather, he is the universal and sovereign God who rules and reigns over all of his creation (Deut. 32:8; Acts 17:26).

(10:1) Now these are the records of the generations of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the sons of Noah; and sons were born to them after the flood.

Why does Moses list these nations? This chapter tells us how Noah’s three sons went on to populate the world: “These three were the sons of Noah, and from these the whole earth was populated… Out of these the nations were separated on the earth after the flood” (Gen. 9:19; 10:32). This is not an “an exhaustive list of all peoples.”[3] Moses knows about more nations than those listed here (e.g. Deut. 2:10-12), but he lists enough “to make the point that mankind is one, for all its diversity, under the one Creator.”[4] Moreover, this sets up the scene for the world empire of Babel in chapter 11, as well as the world’s first recorded human tyrant: Nimrod. He ruled over Babel, which would later become Babylon. This is a type throughout the Bible for human empires in rebellion to God. At the end of history, we read that Babylon’s “sins have piled up as high as heaven, and God has remembered her iniquities” (Rev. 18:5).

Why is there the repeated pattern of 70? Moses lists exactly 70 nations in this list, and most of the genealogies come in sets of seven. Sailhamer[5] thinks that this number communicates the totality of the nations. Eventually Abraham would bring a blessing to all of the nations (Gen. 12:3), and there could be symbolism in the fact that the book ends with 70 of Abraham’s descendants (Gen. 46:27). Later, Moses writes, “When the Most High gave the nations their inheritance, when He separated the sons of man, He set the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the sons of Israel” (Deut. 32:8).

God included this chapter to show that he is sovereign over the nations. All of these nations unite in chapter 11 to overthrow God at the Tower of Babel. But with a wave of his hand, God sends them into confusion.

(1) Japheth: Island Nations

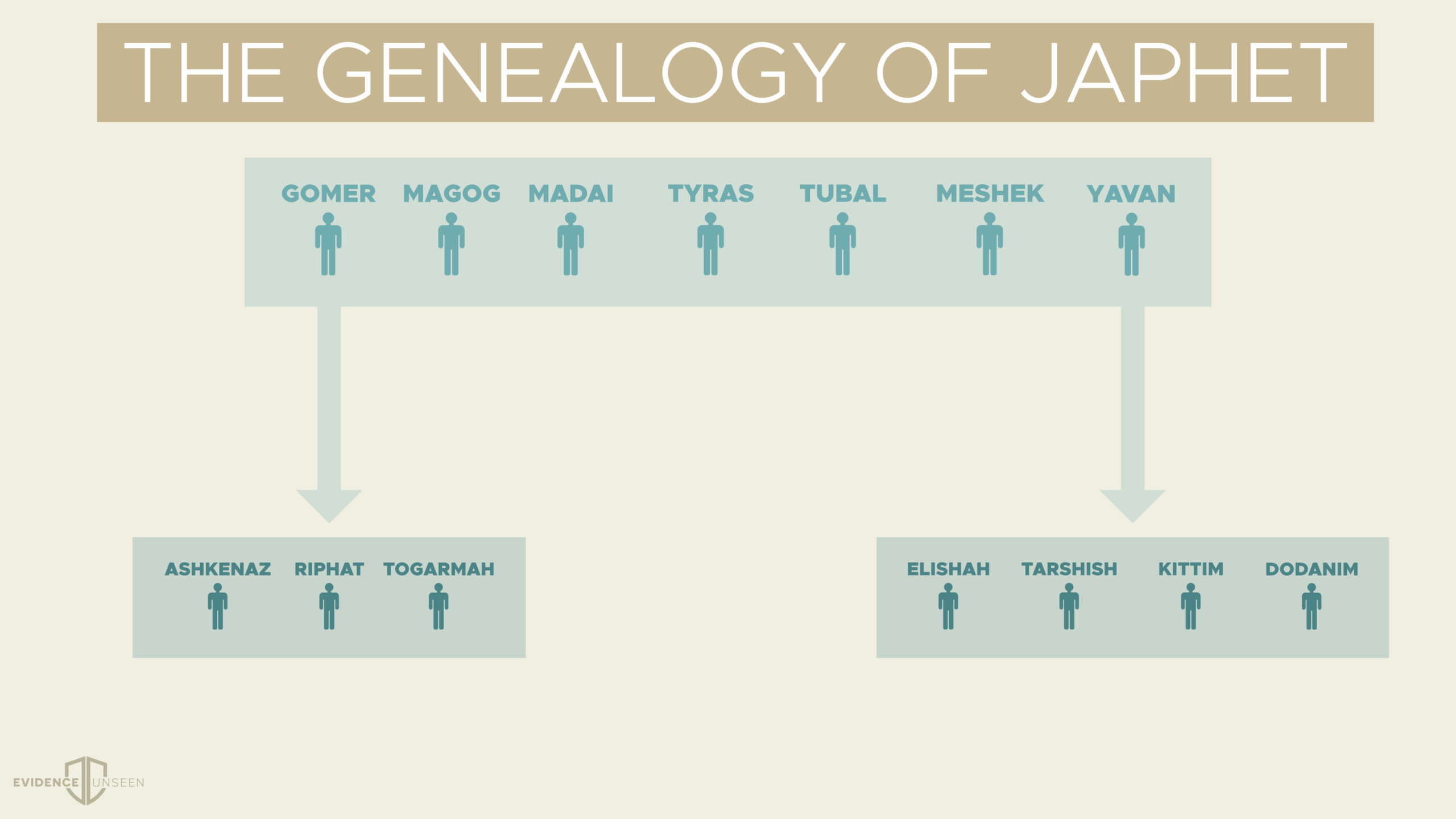

(10:2-5) The sons of Japheth were Gomer and Magog and Madai and Javan and Tubal and Meshech and Tiras. 3 The sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz and Riphath and Togarmah. 4 The sons of Javan were Elishah and Tarshish, Kittim and Dodanim. 5 From these the coastlands of the nations were separated into their lands, every one according to his language, according to their families, into their nations.

There are 14 nations in all—7 sons and 7 grandsons. Moses doesn’t give an exhaustive list. He doesn’t mention the sons of Magog, Madai, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras. The goal of the author isn’t to give an “exhaustive list,” but a “complete list” of 70 nations.[6]

Gomer likely refers to the Cimmerians, who were a “nomadic people to the north of the Black Sea, who later overran much of the region of Anatolia in the seventh century BC.”[7] Gomer appears at the end of history as well, along with his son Beth Togarmah (Ezek. 38:6). Wenham writes, “The Cimmerians were a powerful group of Indo-European origin who came from southern Russia and posed a considerable challenge to Assyria in the eighth and seventh centuries. They eventually settled in Asia Minor.”[8]

Magog, Tubal, and Meshech are mentioned again when referring to the battles at the end of human history (Ezek. 38-39). These are nations to the north (Ezek. 38:6).

Madai likely refers to the Medes, who are “found west of the Caspian Sea in the ninth century BC.”[9] They inhabited modern day northwest Iran.

Javan likely refers to the Ionians, who were “a branch of the Greeks, for whom this is the standard name in the Old Testament (e.g. Dan. 8:21).” This name is found in the “Ugaritic texts of the fourteenth century BC.”[10]

Tiras might refer to the Etruscans, or to the sea peoples of Turcsha around the Aegean Sea.[11]

Ashkenaz likely refers to the Scythians (Jer. 51:27). The Scythians were located on “the Russian steppes that occupied areas north and east of the Black Sea.”[12] Hamilton[13] identifies this with Armenia.

Riphath is unknown but might be “Anatolia.”[14]

Togarmah (or Beth Togarmah, Ezek. 27:14; 38:6) is in Asia Minor.[15] It might be “identified with the area between the upper Halys and the Euphrates.”[16]

Elishah is the “cuneiform name for the island of Cyprus.”[17] (Ezek. 27:7).

Tarshish was known for its ships (1 Kin. 10:22) and metals (Ezek. 27:12). It could be located in Asia Minor (“Tarsus” or “Tharros”) or Spain (“Tartessus”).[18]

Kittim refers to the Island of Cyprus (Num. 24:24; Isa. 23:1, 12; Jer. 2:10; Ezek. 27:6).

Rodanim (or Dodanim) might refer to the people of Rhodes. However, the MT calls this Dodanim. If Dodanim is the correct reading, then the location is uncertain. The more difficult reading should be preferred. Therefore, Wenham writes, “Dodanim might be identified with the land of Danuna mentioned in the Amarna letters, apparently north of Tyre. Inscriptions of Rameses III mention a people Dnn among the invading sea peoples. And Homer sometimes gives the name Danaeans to those who besieged Troy. Sargon II’s inscriptions mention the Yadan̄na, apparently Greek-speaking inhabitants of Cyprus. Despite the widespread mention of ‘dnn’ peoples in antiquity, it cannot be certain that the Dodanim are identical, given the variant spelling (cf. EM 2:626-27). Another possibility is that they are the Dodanoi, i.e., the inhabitants of Dodona, home of the oldest Greek oracle.”[19]

(2) Ham

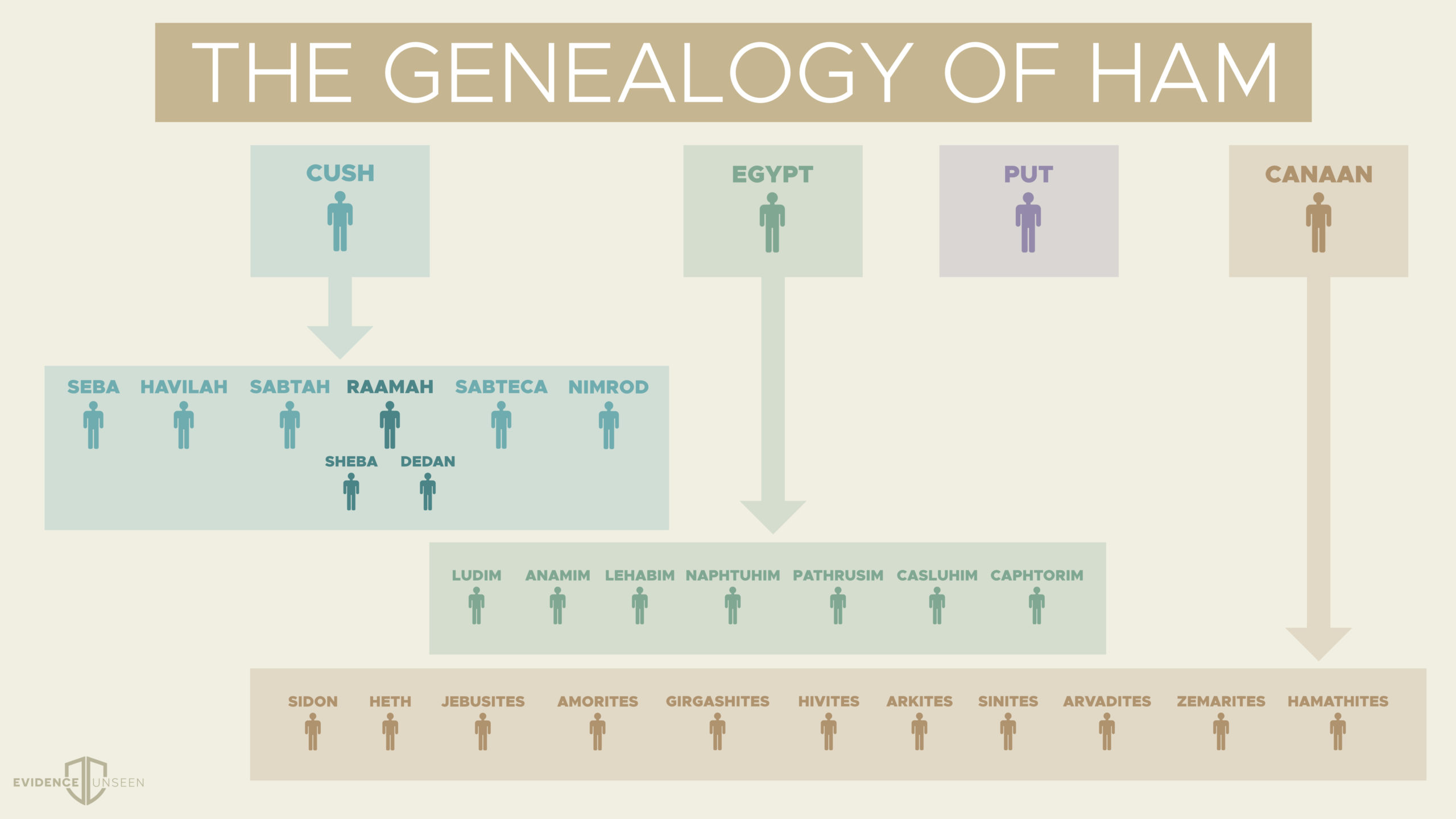

(10:6) The sons of Ham were Cush and Mizraim and Put and Canaan.

Cush could refer to the Ethiopians or the Kassites—east of Assyria: “This passage suggests that they are linked.”[20] Waltke states that it refers to Nubia and Sudan, or more broadly “the country bordering the southern Red Sea; the land of the Kassu, along the Araxes.”[21] Mathews[22] states it refers to Nubia—south of Egypt. Wenham thinks that it is associated with Ethiopia. However, he writes, “It probably covers a variety of dark-skinned tribes (cf. Jer 13:23) living beyond the southern border of Egypt. Note that most of Cush’s descendants listed in the next verse seem to be located in Arabia.”[23]

Mizraim is a transliteration of the Hebrew word for Egypt.[24]

Put is disputed, but it most likely refers to Libya.[25]

Canaan refers to southern Syria, Phoenicia, and “the whole of Palestine west of Jordan.”[26]

Nimrod: A digression on the first recorded tyrant

(10:7) The sons of Cush were Seba and Havilah and Sabtah and Raamah and Sabteca; and the sons of Raamah were Sheba and Dedan.

This region refers to Arabia in general, as well as African nations.[27]

Havilah could refer to “somewhere in Arabia” based on Genesis 25:18 and 1 Samuel 15:7.[28]

Sabtah refers to the Astaboras (Abare) according to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.2). However, the “popular modern suggestion is that it refers to Sabota, the capital of Hadramaut, nearly 270 miles north of Aden.”[29]

Raamah was a “trading center associated with Sheba” according to Ezekiel 27:22. It is near “northern Yemen.”[30]

Sabteca is unknown.

Sheba exported precious metals and spices (Ps. 72:10, 15; Isa. 60:6). It was “established at the beginning of the first millennium BC and had its capital at Marib, about two hundred miles north of Aden in southwest Arabia.”[31]

Dedan is “said to be a descendant of Abraham (25:3) and an important trading center (e.g., Ezek 27:20; 38:13). An inscription has assured its precise location at Al-Alula, seventy miles southwest of Tema. The settlement there dates from the first millennium b.c.”[32]

(10:8-12) Cush became the father of Nimrod; he became a mighty one on the earth. 9 He was a mighty hunter before the LORD; therefore it is said, “Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before the LORD.” 10 The beginning of his kingdom was Babel and Erech and Accad and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. 11 From that land he went forth into Assyria, and built Nineveh and Rehoboth-Ir and Calah, 12 and Resen between Nineveh and Calah; that is the great city.

Nimrod’s name means “we shall rebel.”[33]

Ninevah was the “most important city of Assyria after Ashur.” It goes back to 4,500 BC, and it is located near modern-day Mosul.”[34]

Rehoboth-Ir literally means the “city squares.” Wenham writes, “This may be the name of a suburb of Nineveh, a description of Nineveh itself… or even an interpretation of the name of the city of Ashur.”[35]

Calah is “twenty-four miles south of Nineveh,” and it goes back to the “early third millennium.”[36]

Resen could refer to Hamam Ali on the Tigris River—eight miles south of Nineveh.[37]

“Mighty hunter” (gibbōr bāʾāreṣ) means “champion warrior”[38] or “tyrant,”[39] and it is the same term is used of Goliath the “champion” (1 Sam. 9:1) as well as the “mighty men, who were of old” (Gen. 6:4).

“Before the Lord.” This doesn’t mean that God approved of him. It means that “even in God’s estimation Nimrod is a mighty warrior and tyrant.”[40] This expression also refers to how the earth was “corrupt in the sight of God” (Gen. 6:11).

Even though Nimrod was powerful, his nation was Babel. In chapter 11, we see the futility of Babel. That being said, this nation takes on a “larger than life symbolic value for the city of Babylon”[41] that eventually culminates in the final world empire (Mic. 5:6; Rev. 17:5).

Ham’s descendants continued

(10:13-14) Mizraim became the father of Ludim and Anamim and Lehabim and Naphtuhim 14 and Pathrusim and Casluhim (from which came the Philistines) and Caphtorim.

Among other things, Moses describes the real estate for the land of Canaan. Since most of these are in the Hebrew plural (–ʾîm), he is describing the people groups in this region as well. These are people groups in Asia Minor, Egypt, and Crete.[42]

The Philistines don’t appear in history until far later. However, Mathews writes, “‘Philistine’ was an elastic term and could refer to a number of Aegean groups that migrated to Canaan, including those cited in Egyptian sources. This would accommodate the use of “Philistine” in both passages.”[43]

Ludim are likely the Lydians: “This form reappears in Isa 66:19; Ezek 27:10; 30:5; and may well refer to the Lydians. However, the “Ludim” cannot be identified, but it would seem likely that they lived in or near Egypt.”[44]

Anamim “might point to a home in Egypt west of Alexandria.”[45]

Lehabim “generally regarded as an alternative spelling of “Lubim,” the Libyans, inhabitants of North Africa west of Egypt.”[46]

Naphtuhim is somewhere in northern Egypt.[47]

Pathrusim is “the southern part of the country which stretches from Cairo to Aswan.”[48]

Casluhim is unknown.

Caphtorim are the Cretans (Deut. 2:23).

(10:15-20) Canaan became the father of Sidon, his firstborn, and Heth 16 and the Jebusite and the Amorite and the Girgashite 17 and the Hivite and the Arkite and the Sinite 18 and the Arvadite and the Zemarite and the Hamathite; and afterward the families of the Canaanite were spread abroad. 19 The territory of the Canaanite extended from Sidon as you go toward Gerar, as far as Gaza; as you go toward Sodom and Gomorrah and Admah and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha. 20 These are the sons of Ham, according to their families, according to their languages, by their lands, by their nations.

The Jebusites refers to the people of Jerusalem (Josh. 15:8). The Israelites had to confront these various peoples, as we will see throughout the rest of the Pentateuch in particular, and the OT as a whole.

Sidon refers to the Canaanites.

Heth refers to the land of the Hittites. It could refer to “the pre-Israelite inhabitants of the hill country in the days of the patriarchs and somewhat later.”[49]

The Amorites are well-known in the OT. Wenham observes, “The OT… seems to use the term rather loosely, either of any of the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Canaan (Josh 10:5) or Transjordan (Og and Sihon are called Amorites in Deut 3:8), or specifically of certain people who dwelt in the hill country as opposed to Canaanites who tended to live in the cities on the coastal plain (Josh 11:3).”[50]

The Girgashites can be seen throughout the OT (Gen. 15:21; Deut 7:1; Josh 3:10; 24:11).

The Hivites were located “well north in Lebanon and Syria (Josh 11:3; Judg 3:3), but some are found as far south as Shechem and Gibeon (Gen 34:2; Josh 9:1, 7).”[51]

The Arkites (Arqa) were “twelve miles northeast of Tripoli” and date as far back as the “Early Bronze Age.”[52]

The Sinites are unknown: “It was evidently a Phoenician coastal town near Arqa.”[53]

The Arvadites refers to Arvad and modern-day Ruad (see Ezek. 27:8, 11), which is “an island city lying two miles off shore, fifty miles north of Byblos.” It was the “most northerly Phoenician city.”[54]

The Zemarites are unknown.

The Hamathites refer to modern-day Hama on the Orontes. Wenham writes, “A city has been on this site from about 4000 BC. For a while, it was a vassal of David and Solomon (2 Sam 8:9-10; 2 Chr 8:4), and later it was reconquered by Jeroboam II (2 Kgs 14:28). It is most often mentioned in the OT as being near the northern border of the promised land of Canaan (e.g., Num 34:8; Josh 13:5).”[55]

The territory of the Canaanites extended from Sidon as you go toward Gerar, as far as Gaza; as you go toward Sodom and Gomorrah and Admah and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha.

(3) Shem

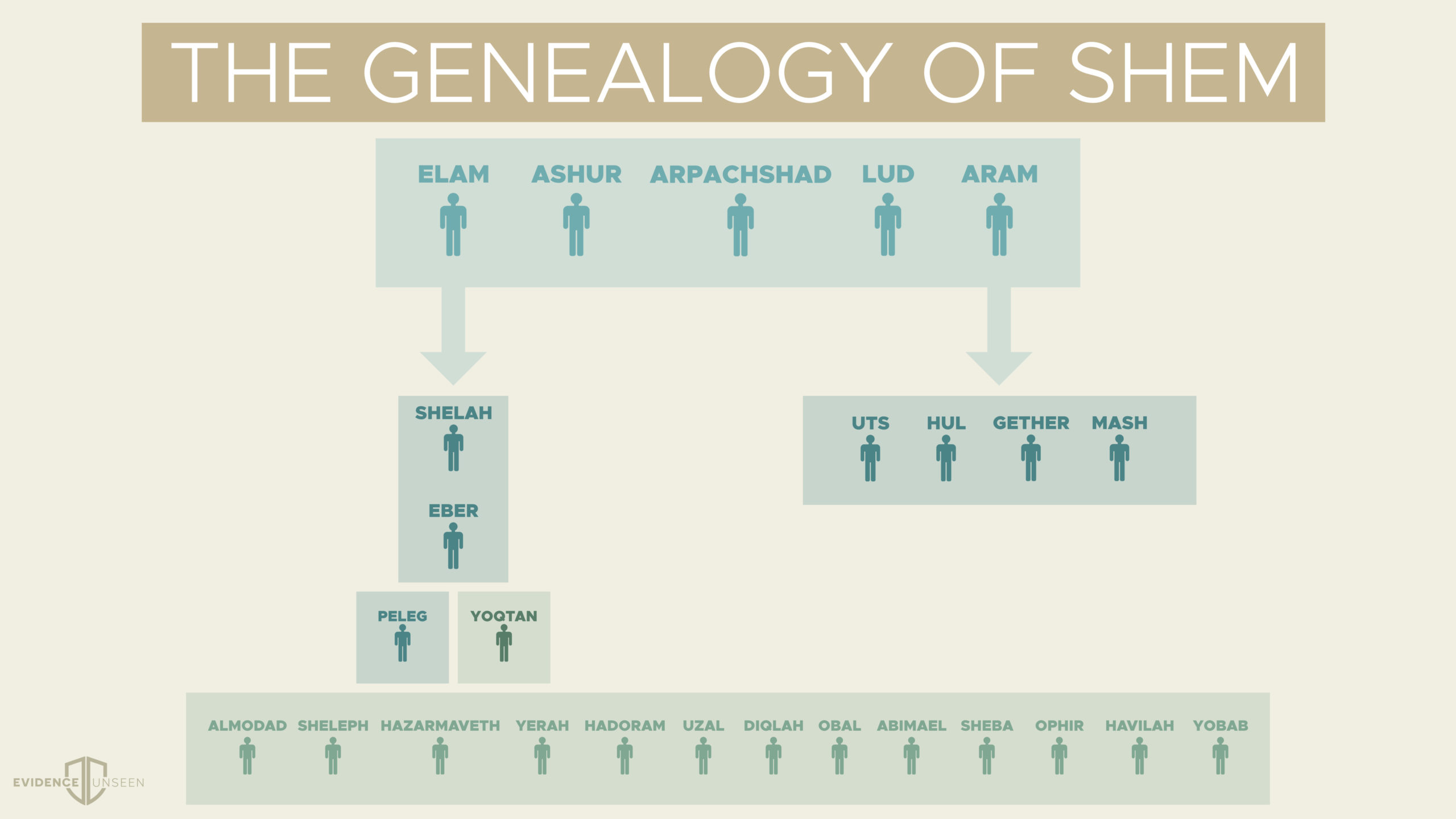

(10:21-31) Also to Shem, the father of all the children of Eber, and the older brother of Japheth, children were born. 22 The sons of Shem were Elam and Asshur and Arpachshad and Lud and Aram. 23 The sons of Aram were Uz and Hul and Gether and Mash. 24 Arpachshad became the father of Shelah; and Shelah 1became the father of Eber. 25 Two sons were born to Eber; the name of the one was Peleg, for in his days the earth was divided; and his brother’s name was Joktan. 26 Joktan became the father of Almodad and Sheleph and Hazarmaveth and Jerah 27 and Hadoram and Uzal and Diklah 28 and Obal and Abimael and Sheba 29 and Ophir and Havilah and Jobab; all these were the sons of Joktan. 30 Now their settlement extended from Mesha as you go toward Sephar, the hill country of the east. 31 These are the sons of Shem, according to their families, according to their languages, by their lands, according to their nations.

The term “Eber” (‘ēber) seems to be the root for “Hebrew,” though this “remains disputed.”[56] Of course, the Hebrews were descendants of Shem or the “Semites.” Wenham writes, “Since 10:24 and 11:13-14 make Shem the great-grandfather of Eber, ‘father’ must be understood here in the looser sense of ‘forefather, ancestor.’”[57]

Shem is the ancestor from whom we get the line of Abraham, who will become central to the patriarchal narratives (Gen. 12-50) as well as the rest of the Bible. The descendants of Shem (or the “Semites”) diverge right down the middle. Sailhamer explains, “In arranging the genealogy of Shem in such a way, the author draws a dividing line through the descendants of Shem on either side of the city of Babylon. The dividing line falls between the two sons of Eber, that is, Peleg and Joktan. One line leads to the building of Babylon and the other to the family of Abraham.”[58] This could be what the author meant by “in his days the earth was divided” (Gen. 10:25). The difference is clear. On the one side, we see “those who seek to make a name for themselves in the building of the city of Babylon,” and on the other side we find “those for whom God will make a name in the call of Abraham.”[59]

“Elam and Asshur and Arpachshad and Lud and Aram.” These are in the region of Iran and Iraq.[60]

Elam dates to the third millennium BC: “ Kedorlaomer (14:1, 9) was king of Elam, and in later times Assyrians deported Israelites to Elam.”[61]

Asshur refers to Assyria.

Arpachshad was held to be Babylon (Antiquities 1:144). Wenham[62] rejects this. Babylon is mentioned in verse 10. It’s also a weak connection that the last three letters of Arpachshad (kšd) is similar to the “Chaldeans” (kaśdîm).

Lud could refer to the Lydians (Assyrian Luddu).

Aram or the Arameans (Gen. 25:20; 31:20; Deut 26:5) became “significant historically as a people at the end of the second millennium, when a series of Aramaean states in Syria became important.”[63]

“Uz and Hul and Gether and Mash.” These could be the Arameans and Edomites, who were located in Syria and Mesopotamia.[64] We know very little about these groups which “argues for the antiquity of this data.”[65]

“Shelah” seems connected to Judah (Gen. 38:5, 11, 14, 26; 46:12; Num. 26:20; 1 Chron. 2:3; 4:21-23).

Eber. See verse 21.

“Two sons were born to Eber; the name of the one was Peleg, for in his days the earth was divided; and his brother’s name was Joktan.” Peleg (peleg) is a play on words with the word divided (niplĕgâ). This could refer to the scattering that occurs at the tower of Babel.[66] It could also refer to the splitting of the people groups before Babel.

Scientist Hugh Ross takes this quite literally to refer to the dividing of the Bering Strait, separating the continents of Asia and North America. He writes, “Genesis 10:25 says that ‘the world was divided’ in the days of Peleg. In the Genesis 11 context of humanity’s migration beyond the Middle East, this dividing may well refer to the breakup of the great land bridges—physical connectors that joined Siberia to Alaska, Britain to France, Korea to Japan, Queen Charlotte Islands to mainland British Columbia, for example—near the close of the last ice age. Carbon-14 dating indicates that sea levels rose to make both the Bering and Hecate Straits impassable at about 11,000 years ago. If Peleg lived at the time those bridges broke apart some 11,000 years ago and Abram, about 4,000 years ago, and if the patriarch’s lifespans recorded in Genesis 11 are proportional to the passage of time, then Noah would have been alive roughly 40,000 years ago and Adam and Eve anywhere from 60,000 to 100,000 years ago… While the biblical statement of the earth’s division seems consistent with new discoveries about the geographical separation and with the timing of the Genesis 9-11 account of God’s scattering humanity over the whole face of Earth, no firm conclusions can be drawn. Genesis 10:25 simply says that the earth was divided in the time of Peleg. However, because this name appears halfway down the list from Shem to Abraham, the estimated biblical date for Peleg does seem to match the scientific dates for the collapse of the world’s land bridges. Here is the scenario that emerges from integrating the biblical and scientific data: When Noah’s descendants refused to ‘fill the earth,’ God intervened to scatter them far beyond their land of origin. Thousands of years later, that scattering reached the geographical limits of the eastern hemisphere. Approximately 14,000 years ago, a passable land bridge formed from the eastern to western continents. For a few thousand years the scattering of humanity into all the habitable landmasses continued. When that scattering was complete, roughly 11,000 years ago, the land bridge broke, preventing humanity from reuniting and repeating the sins of the preflood and early postflood peoples. As for Australia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and the British Isles, archaeological evidence shows that humans settled them thousands of years prior to the settling of the Americas. The straits separating these lands from larger nearby landmasses are warmer and calmer than the Bering and Hecate, for example. They may well have been passable in boats. Some evidence suggests that earlier land or semi-land bridges did exist in these locations. However, when the Bering and Hecate land bridges were disappearing, absolute sea levels were rising by about seventeen feet (five meters) per century. This rise would have sufficiently broadened the straits separating Australia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and Britain from the Asian and European mainland to hinder the return of their inhabitants.”[67]

Joktan might refer to modern-day southern Arabia.[68]

(10:26-29) Joktan became the father of Almodad and Sheleph and Hazarmaveth and Jerah 27 and Hadoram and Uzal and Diklah 28 and Obal and Abimael and Sheba 29 and Ophir and Havilah and Jobab; all these were the sons of Joktan.

The peoples mentioned in this section generally refer to those in the “south Arabian peninsula.”[69] Moreover, many of these are personal names, rather than geographical locations.

Obal might be a Yemenite tribe.[70]

Epilogue

(10:32) These are the families of the sons of Noah, according to their genealogies, by their nations; and out of these the nations were separated on the earth after the flood.

This sets the stage for the united world empire of Babel.

[1] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 174.

[2] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 346.

[3] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 162.

[4] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 1, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), 112.

[5] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 98.

[6] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 100.

[7] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 167.

[8] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 216.

[9] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 1, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), 113.

[10] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 1, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), 113-114.

[11] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 167.

[12] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 441.

[13] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 332.

[14] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 332-333.

[15] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 441.

[16] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 218.

[17] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 333.

[18] Mathews writes, “the association of Tarshish with other places, such as Arabia (e.g., Ps 72:10; Ezek 38:13), recommends that “Tarshish” may describe a particular activity (such as smelting) rather than a locale. This would explain how “Tarshish” could speak of different sites.” K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 442.

[19] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 219.

[20] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 1, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), 114.

[21] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 168.

[22] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 444.

[23] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 221.

[24] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 445.

[25] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 168.

[26] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 168.

[27] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 168.

[28] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 221.

[29] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 221.

[30] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 221-222.

[31] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 222.

[32] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 222.

[33] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 222.

[34] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[35] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[36] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[37] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[38] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 450.

[39] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.169.

[40] Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 169.

[41] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 101.

[42] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 453.

[43] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 454.

[44] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[45] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[46] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[47] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[48] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 224.

[49] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 225.

[50] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 225-226.

[51] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 226.

[52] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 226.

[53] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 226.

[54] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 226.

[55] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 226.

[56] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 460.

[57] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 228.

[58] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 102.

[59] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 102.

[60] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 461-462.

[61] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 228.

[62] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 228.

[63] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 230.

[64] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 462-463.

[65] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 230.

[66] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 463.

[67] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), in loc.

[68] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 231.

[69] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 464.

[70] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 231.