Unless otherwise stated, all citations are taken from the New American Standard Bible (NASB).

This commentary gives a verse-by-verse interpretation of Genesis 1-3 that also interacts with the scientific data. It compares the various interpretative models (e.g. Old Earth, Young Earth, Gap Theory, Literary Framework, etc.).

This commentary gives a verse-by-verse interpretation of Genesis 1-3 that also interacts with the scientific data. It compares the various interpretative models (e.g. Old Earth, Young Earth, Gap Theory, Literary Framework, etc.).

Before the Seven Days of Creation (Gen. 1:1-2)

(1:1) “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”

(Gen. 1:1) Does the Bible teach creatio ex nihilo (or a creation out of nothing)? We disagree with the small minority of English translations that render this as, “When God began to create” (e.g. NEB, or margins of NRSV and CEV). This translation renders this as a dependent or temporal clause, rather than as an independent clause. This is a minority translation, and it should be rejected for several reasons:

For one, all of the ancient translations agree with the view that this refers to an absolute beginning (e.g. the Septuagint, the Vulgate, Aquila, Theodotion, Symmachus, the Targum of Onqelos, cf. Jn. 1:1, 3; Heb. 11:3).[1]

Second, Hebrew dependent clauses are usually not this long and cumbersome. If this is a dependent clause, then the sentence wouldn’t end until after verse 3. This is very much “unlike a true Hebrew sentence, especially an introductory sentence.”[2]

Third, conventional Hebrew grammar rejects this minority interpretation. These first two verses do not contain wayyiqtol verbs, or what is called the waw-consecutive.[3] The waw-consecutive refers to perfect and imperfect Hebrew verbs which are preceded by the conjunction waw (pronounced “vav”). According to Hebrew grammarians, these are used primarily in “narrative sequences to denote consecutive actions, that is, actions occurring in sequence.”[4] However, in Genesis 1:1-2, we do not see sequential action. Instead, God created the universe before space-time existed.

Fourth, the book of Genesis is a book about beginnings. But if this translation is correct, then the beginning of the book is not the beginning at all! Under this view, it has “clearly failed at the most crucial point if, in fact, the best it can say is that at the very start matter just happened to be around.”[5]

Fifth, the rest of the OT affirms God’s creation of the universe from nothing. Isaiah states that God is “the maker of all things” (Isa. 44:24), and Jeremiah writes that God is the “maker of all” (Jer. 10:16). Isaiah writes, “I am God, and there is no other; I am God, and there is no one like Me, 10 declaring the end [ʾaḥarîṯ] from the beginning [mērēʾšîṯ]” (Isa. 46:10). Isaiah is quoting God and “is thinking in terms of God’s absolute disposition over beginning and end.”[6] Where did all of these OT prophets get this notion of creatio ex nihilo? Look no further than Genesis 1:1. As usual, the Bible is its best interpreter.

Sixth, the NT affirms God’s creation of the universe from nothing. Using the same language of Genesis 1, John writes, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… All things came into being through Him, and apart from Him nothing came into being that has come into being” (Jn. 1:1, 3). Also alluding to Genesis 1, the author to the Hebrews writes, “The worlds were prepared by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things which are visible” (Heb. 11:3).

In conclusion, Genesis 1:1 teaches a beginning of space-time, and an absolute beginning to the universe.[7] It refers to “the beginning of time itself, not to a particular period within eternity”[8] and an “absolute beginning point in time.”[9] Most translators and commentators agree with this understanding.[10]

Why would some translations deviate from the clear meaning of the text? Boice and Young wonder if scholars are trying to conform Genesis to the Babylonian creation account (the Enuma Elish) which begins with the words, “When on high the heavens were not named, and below the earth had not a name…” Yet, this is a “prejudicial desire to have the Genesis account conform to it.”[11] We agree with Matthews who writes, “Genesis 1:1 has no exact syntactical parallel among pagan cosmogonies… That ancient cosmogonies characteristically attributed the origins of the creator-god to some preexisting matter (usually primeval waters) makes the absence of such description in Genesis distinctive… the startling absence of precreated matter distinguishes Israelite cosmogony from its rivals in the pagan Near East.”[12]

(Gen. 1:1) Does the Bible teach that God created the universe or just the Planet Earth? The expression the “heavens and earth” (hashamayim we ha ‘erets) uses a literary device called a merism—a figure of speech that implies “the totality of the universe.”[13] For instance, we might say that we searched “high and low” or in every “nook and cranny.” Even though these expressions only mention isolated parts, they refer to everything in between—much like saying, “I love you from your head to your toes.”

The Hebrews had no word for “universe,” so this merism refers to the entirety of the universe. In every other usage of this expression in the OT (Gen. 2:1, 4; Deut. 3:24; Isa. 65:17; Jer. 23:24), this “phrase functions as a compound referring to the organized universe.”[14] This is why the prophet Joel equated the “sun, moon, and stars” with “the heavens and the earth” (Joel 3:15-16).

Even in the Egyptian, Akkadian, and Ugaritic cultures, the phrases “heavens and earth” referred to the universe, and therefore, it could be translated, “In the beginning God created everything.”[15] Since the Hebrews only had a 3,000-word vocabulary,[16] they often needed to combine words to convey a novel meaning. In this case, the Hebrews used this compound expression.

What can we conclude from this opening verse of the Bible?

God is the sole Creator of the universe. He is the main actor in creation, being mentioned 35 times in this opening section. In fact, he is mentioned “in as many verses of the story.”[17] This passage affirms that God is self-existent, self-sufficient, and eternal (Gen. 21:33; Ps. 90:1-2; Rev. 1:8; 4:8; 21:6). From a devotional perspective, we need God at the beginning of our worldview, and indeed, at the beginning of every new venture in our lives.[18]

This passage denies atheism and naturalism. In the biblical worldview, we do not begin with “molecules in motion.” We begin the world with an infinite Mind—not mindless matter.

This passage denies any form of pantheism. God is not one and the same as creation. He existed before creation, and he is distinct from creation.

This passage denies any form of polytheism and idol worship. Later, the OT prophets and psalmists refuted idolatry by appealing to God as the Cosmic Creator. The psalmist states, “All the gods of the peoples are idols, but the LORD made the heavens” (Ps. 96:5). Likewise, Jeremiah writes, “The gods that did not make the heavens and the earth will perish from the earth and from under the heavens” (Jer. 10:11). We agree with many scholars who argue that Genesis 1 is “a polemic against idolatry,”[19] and this section is filled with “polemical undertones regarding pagan cosmogonies.”[20]

This passage denies humanism. God was the one who existed in the beginning, and he is the Cosmic Creator of everything. Therefore, the universe belongs to him—not to us.

This passage denies the teaching of Mormonism. The LDS church affirms an infinite regression of “gods” who have created universes into eternity past, and will create into eternity future. We can’t get one verse into the Bible before seeing it demolish this worldview. The book of Genesis is a book of beginnings (e.g. universe, earth, life, humanity, Israel, etc.), but we read nothing about God having a beginning! As Isaiah writes, “Before Me there was no God formed, and there will be none after Me” (Isa. 43:10).

This passage denies the teaching of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. They contend that God used Jesus (an angel, in their view) to create the universe. However, God didn’t create the universe with anyone’s help, but rather, he created “all alone” (Isa. 44:24). In an orthodox view, Jesus is God. Therefore, he is the Cosmic Creator (Jn. 1:1; Col. 1:16).

(1:2) “The earth was formless and void, and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was moving over the surface of the waters.”

Moses doesn’t tell us how much time transpired between verse 1 and verse 2. The seven days of Genesis do not begin until verse 3. So, the age of the universe and the Earth remain an open question. At this point, Moses focuses on the Planet Earth (or perhaps the localized “land”?), which is “formless and void.”

“Formless and void” (tōhû wābōhû) describes a “wasteland” or “empty land.”[21] The same expression occurs in Jeremiah to refer to the land of Israel being barren: “I looked on the earth, and behold, it was formless and void; and to the heavens, and they had no light” (Jer. 4:23; cf. Isa. 34:11). The term “formless” occurs in Deuteronomy as parallel with a “desert land” (Deut. 32:10-11).

Is the “Spirit of God” the Holy Spirit or just a wind? The term “Spirit” (rûaḥ) can also be translated as “wind.” For instance, after the Flood, God sends a “wind” (rûaḥ) to dry the land. Is that what we’re seeing here in Genesis 1:2?

No, this translation simply doesn’t fit the description that we read. For one, this is not merely a “wind” by itself. It is the “Spirit of God.” Clearly, this description means more than just a mere wind.[22] Second, the “Spirit of God” is “hovering” (ESV, NIV) over the surface of the waters. To state the obvious, a natural wind doesn’t hover! The personal Spirit of God can choose to hover, but not a gust of wind. Third, elsewhere, Moses describes God as “hovering” (yeraḥēp̱) over the people of Israel: “Like an eagle that stirs up its nest, that hovers over its young, He spread His wings and caught them, He carried them on His pinions” (Deut. 32:11). The use of these similar images “both at the beginning of the Pentateuch and at the end suggests that it is the picture of the Spirit of God that is intended here.”[23]

Does “the deep” refer to the goddess Tiamat? Many critics of the Bible contend that the Hebrew word for “deep” (tehôm) is similar to the Akkadian “Tiamat,” whom the Babylonian creation account mentions in the Enuma Elish. Tiamat is the evil monster goddess of the sea, and she faces her death when the god Marduk slays her. In the Enuma Elish, the god Marduk slays Tiamat and uses her corpse to create the heavens and the earth.

However, experts in Assyriology and Egyptology like Alexander Heidel[24] see no connection. Likewise, ancient Near Eastern scholar K.A. Kitchen calls this a “complete fallacy.”[25]

For one, he notes that the Hebrew noun is “unaugmented,” making it a common noun, while the Babylonian word is a “derived form,” making it a proper name. In other words, the context of the Babylonian word implies a goddess, while the context for the Hebrew word implies a common noun. Matthews adds, “There is no place in the Old Testament where the ‘deep’ is personified as it is with Tiamat in the Mesopotamian story.”[26]

Second, the Ugaritic language also used the word (thm) to refer to the “deep,” even as early as the second millennium BC, and this has “no conceivable link with the Babylonian epic.”[27]

Third, the text later states that God brought water from the “deep” (tehôm) to flood the Earth (Gen. 7:11), which surely doesn’t refer to a water goddess. Hamilton writes, “The deep of Gen. 1 is so far removed in function from the Tiamat of Enuma elish that any possible relationship is blurred beyond recognition. The deep of Gen. 1 is not personified, and in no way is it viewed as some turbulent, antagonistic force.”[28]

Fourth, Matthews adds that the Babylonian and Hebrew words both derive from a “common Semitic word.” That is, they both share the same source, and therefore, the “Hebrew is not a derivative of Tiamat linguistically.”[29]

Finally, we might add that the greater context of Genesis 1 shows no struggle between rival gods—unlike the ancient Near Eastern accounts. Thus, Matthews concludes, “The primordial gods of pagan myths are no more than natural phenomena.”[30] The so-called “gods” are merely the inanimate furniture within the universe according to Genesis.

Gap Theory Perspective: Older gap theorists held that the Hebrew in verse 2 can be translated in this way: “The earth became formless and void” (see NIV 1984 note). In their view, a large gap of time occurred between verse 1 and verse 2. How long of a gap existed? The text doesn’t say. But under this reading, the earth seems to have fallen into a state of disorder and destruction. The terms “formless and void” (tohu wabōhû) elsewhere refer to a destroyed and desolate state (Isa. 34:10-11; Jer. 4:23). Isaiah writes, “[The Lord] created the heavens (He is the God who formed the earth and made it, He established it and did not create it a waste place, but formed it to be inhabited)” (Isa. 45:18). In other words, Isaiah is saying that God did not create the world formless. Consequently, gap theorists argue that this could be commentary on how the Earth had become formless and void. Furthermore, the mention of “darkness” being over the surface of the Earth might imply divine judgment (Ex. 10:21; Isa. 45:7; 1 Sam. 2:9).

Other scholars do not hold to the gap theory, but they do acknowledge that an indefinite amount of time could exist between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2. After all, the days of Genesis do not begin until verse 3. OT expert C. John Collins notes that the term “created” (bara) is perfect—not infinitive, and the normal use of the perfect at the beginning of a section “is to denote an event that took place before the storyline gets under way.”[31] So, even if the Earth did not have some sort of Fall, an indefinite gap could still exist. This singular interpretive insight could resolve the age of the Earth controversy. After all, we simply don’t know how long this gap of time could’ve existed.

Day-Age Perspective: Hugh Ross argues that we need to understand the perspective from which the author is writing. According to verse 2, the perspective comes from the “Spirit of God” who “was moving over the surface of the waters.” While we might assume that the observations of the author are from outer space looking downward, Ross argues that the text states that the perspective is from the Spirit looking upward from the surface of the Earth.[32] Lennox agrees, “This, incidentally, may well provide an answer to the question, if most of Genesis 1 is concerned with global phenomena—the heavens, earth, land, sea, sky, and so on—why does it talk about day and night, even though night and day occur simultaneously on different sides of the earth?”[33]

This would explain why everything was dark in the beginning. On our primitive planet, an opaque cloud covered the Earth. Using the language of simile, the psalmist describes the earth as being “covered… as with a garment” (Ps. 104:6). God tells Job, “I made the clouds its garment and wrapped it in thick darkness” (Job 38:9). All of this imagery teaches that the early earth was dark.

In addition, Ross speculates that God created the first single-celled life at this time. Where does he get this from the text? The language of the Spirit “hovering” (ESV, NIV) may describe the first initial creation of God (i.e. single-celled life). This term “hovering” (yeraḥēp) is only used one other time (Deut. 32:11), where it describes an “eagle… that hovers over its young.”[34] Historically, single-celled life was the first to originate on Earth, which would fit with this reading of Genesis 1:2. However, while this is interesting speculation, this is a clear case of concordism, where we are squeezing scientific discoveries into a text. It’s highly doubtful that Moses had this in mind when he wrote that the Spirit was “hovering” over the water.

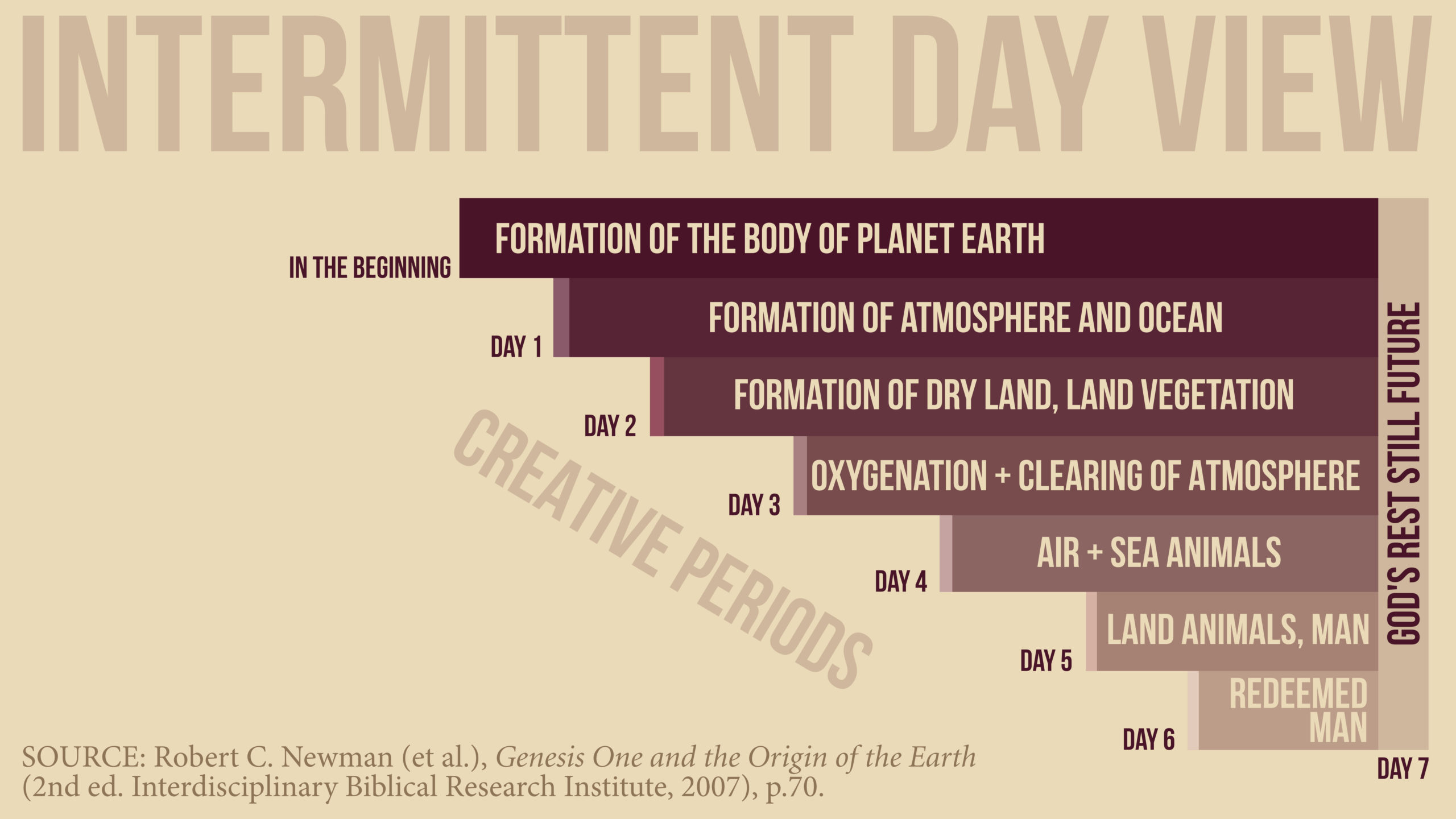

Intermittent-Day View: Newman concurs that we need to read Genesis from the perspective of a viewer on the Earth’s surface. He writes, “Historical events in the Old Testament are relayed from a personal standpoint; that is, events are written as though the writer is personally present and saying, in effect, ‘This is what I saw.’ Accordingly, we propose that Genesis 1 gives a description of what the various creation events would have looked like to an earthbound observer had one been present to see God’s work. Rather than a description of the creation from heaven, the language portrays creation as viewed by one caught up in its midst.”[35] Consequently, he holds that this was a literal day, where day and night were observed. On his view, the second day could have occurred eons later.

Day 1: light and darkness

(1:3) “Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light.”

The text doesn’t state that light came into existence on Day One. Instead, it uses the language “let there be light.” This is only two words in Hebrew.[36] This might simply refer to the function—not the creation—of light. Later, we read the same language for the purpose of the sun—namely, to mark out “seasons, days, and years” (Gen. 1:14).

Day-Age Perspective: Hugh Ross argues that light began to puncture through the opaque clouds around the Earth at this time. From the viewer’s perspective on Earth (Gen. 1:2), the sky would’ve become “translucent,” but not yet “transparent.”[37] Only much later would the sky brighten as it is today. Likewise, Sailhamer contends that this verse does not refer to the “creation of the sun but the appearance of the sun through the darkness.”[38] After all, he argues, the division of the “day” and “night” presuppose the existence of the sun. An ancient reader would know this just as well as a modern one. David Snoke agrees, “For a person standing on the land, in its formless state, the first event of significance is the ignition of the sun. Light appears, but—according to all we know from modern science—the earth was still cloudy, like the planet Venus. Light and darkness alternated as the earth turned on its axis, but the sun, moon, and stars were not visible in the sky. Everything was still murky and swampy.”[39]

Young Earth Perspective: In our estimation, this perspective has great difficulty with this verse. After all, under their strict literalistic hermeneutic, God didn’t create the sun until Day Four. What then does this “light” refer to? YECs believe that this refers to God’s “Shekinah glory” or his “effulgent splendour,”[40] whereby he himself generates light for the Planet Earth until Day Four. Jonathan Sarfati writes, “This light of Genesis 1:3, while not God, was still unique. It wasn’t sourced in the sun or stars—they wouldn’t be created until Day 4… The source of this physical light was probably the Shekinah Glory.”[41] Though, Sarfati is quick to note that this light is “not God” and is “created” by God.

Of course, plants need more than mere light to survive. If the sun, moon, and stars didn’t exist, the entire planet would be inhospitable to life.[42] Therefore, God would need to produce the same mass, energy, gravity, heat, and light as the sun, moon, and stars for the Earth. But if God’s Shekinah glory burned like the Sun, had the gravitational attraction of the Sun, and gave off heat like the Sun, then why not just believe that he had already created the Sun? That is, if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, why would we think it’s God’s Shekinah Glory in disguise?

(1:4) “God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.”

Does “good” refer to a moral or philosophical “good”? Matthews states that the word “good” (ṭôḇ) has a wide semantic range that can refer to “happy, beneficial, aesthetically beautiful, morally righteous, preferable, of superior quality, or of ultimate value.”[43] Sailhamer[44] doesn’t understand the term “good” (ṭôḇ) in a philosophical or moral sense either. That is, the text isn’t claiming that the planet was morally perfect. Rather, the term refers to being “beneficial for man.” This view is plausible for a number of reasons:

For one, this fits with Eve who “saw that the tree was good for food” (Gen. 3:6). That is, it was beneficial for humans. Moreover, the parallel of God and Eve “seeing” seems to offer a distinct contrast between God’s view and the view of humans.

Second, God calls impersonal objects like light, water, and land to be “good” (ṭôḇ). Impersonal objects are neither morally good nor evil. But they can be considered “good” insofar as they beneficial for the habitation of humans.

Third, this helps answer the difficulty that there was animal predation and animal death on the Earth for 3.8 billion years before the Fall. If this reading is correct, then this would imply that moral perfection is not being communicated—only goodness for the habitation for humans which is, of course, the context. To be fair, hoowever, this view has difficulty with understanding the tree of the knowledge of “good” (ṭôḇ) and “evil” (raʿ). Surely, this later use refers to moral goodness (ṭôḇ).

“God separated the light from the darkness.” The separation seen throughout this chapter shows that there is a personal Designer of the universe. Regarding the repetition of God “separating” aspects of his creation, Kidner writes, “This way lies cosmos… and the other way chaos.”[45]

(1:5) “God called the light day, and the darkness He called night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.”

The NASB has the correct translation here (“one day”). This is a cardinal number (“Day One”), whereas the subsequent days are ordinal numbers (“the second day… third day… fourth day… fifth day…,” etc.).

Why does God name his creation? In the ancient Near East, this was a way to “assert sovereignty”[46] over something (Gen. 2:20; 2 Kin. 23:34; 24:17). Thus, God is asserting his sovereignty over his creation. He is ultimately in charge of his creation.

Day-Age Perspective: God isn’t creating anything new, but simply naming his creation and asserting his rightful sovereignty.

Young Earth Perspective: YECs are adamant on the days of Genesis being 24-hours. Jonathan Sarfati writes, “God himself in Genesis 1:5 is defining what a day is: a darkness (night) and light (day) cycle, ‘there was evening and there was morning, one day.’ One rotation of the earth equals one day.”[47] This is odd, to say the least, because the Hebrew word yom is used twice in this very passage, and both usages have different timeframes! The “light” is called “day” (i.e. 12 hours) and the entire cycle is called “day” (24 hours in his view). Moreover, Sarfati believes that God defined this day before the existence of the sun (which was created on Day Four).

Day 2: Separating waters (the “expanse”)

(1:6) “Then God said, ‘Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’”

Does the “expanse” refer to a metallic “firmament” above the Earth? Sarna[48] and Currid[49] argue that the “expanse” (rāqîaʿ) should actually refer to a solid dome that encases the Earth. They argue that the pre-scientific Hebrews believed that the Earth was surrounded by this solid dome, and that water poured through slits in the dome to bring rain. Similarly, Job describes the “skies” (shachaq) as being as “strong as a molten mirror” (Job 37:18). Later in Genesis, we read that God opened “the floodgates of the sky” (Gen. 7:11-12; 8:2). Thus, these commentators argue that the author of Genesis believed in a hardened dome around the Earth, which had sluice gates that let the water through.

This is nonsense. To begin, the English translations render this word in a variety of ways. Some English translations have translated this word as “firmament” (NKJV, AV, RSV), “vault” (TNIV), “vaulted dome” (LEB), or “dome” (NRSV). However, others render this word as “expanse” (NASB, ESV, NIV, NET, HCSB, YLT), “space” (NLT), “huge space” (NIRV), or simply “something” (NICV). Why all of the confusion?

The word “expanse” (rāqîaʿ) means stomping with your feet, resulting in “spreading out or stretching forth.”[50] Some translators place the emphasis on the concept of stretching, while others place the emphasis on the result of the stretched material. This is why some translate it as a space that is “stretched out,” while others translate it as a hard material that needs “stamped.”

So, which is it? The best way to understand the meaning of a word is by its context. Multiple contextual markers indicate that Moses was describing a spatial expanse between the water on the Earth, and the water in the sky.

First, in Genesis 1:8, this “expanse” is explicitly called “heaven” or “sky” (šāmayim). The “sky” (šāmayim) cannot be a hardened dome because God threatens to make the skies “like iron” (Lev. 26:19), cutting off the rain for the people. If Moses believed the sky was a “metallic vault,” then “the above passages would be meaningless, since the skies would already be metal.”[51]

Second, not only do the sun, moon, and stars exist in the expanse (Gen. 1:14), but the birds fly in this area as well (Gen. 1:20). Surely ancient observers knew as well as we do today that birds fly in the open air—not in a hardened dome! The birds fly “above” (ʿal) the expanse—not below it. Out of the 900 times that this term is used, it means “‘go up’ (over 300 times), ‘come up’ (over 160 times) and ‘ascend’ (17 times).”[52] This suggests that “that the birds are flying upon the air rather than beneath a dome.”[53] This refers to “the formation of the atmosphere after the earth has become a solid body.”[54]

Third, the most natural reading of the waters above is most “likely a reference to the clouds.”[55] The ancient Jews didn’t need to know meteorology to know that rain came from clouds (Judg. 5:4; 2 Sam. 22:12; Job 26:8; 37:11; Ps. 18:11; 77:17; Prov. 16:15 Eccl. 11:3; Isa. 5:6). Even other ancient Near Eastern texts assumed that rain came from the clouds above.[56] This is why God gave Noah the sign of the rainbow in the clouds, because these clouds were one of the main sources of the flood waters (Gen. 9:12-16).

Fourth, Moses surely didn’t believe that clouds were solid surfaces, because he believed humans could enter into clouds (Ex. 24:18; cf. Ezek. 1:4; Lk. 9:34). Of course, these clouds are examples of theophanies (where God appears to people), but these “descriptions are still suggestive about the Israelites’ experiences with ordinary clouds.”[57]

Finally, regarding Job 37, Poythress writes, “The simile in Job 37 simply compares the Sun’s brightness on a clear day to the painfully bright reflection of light from such a mirror.”[58] We agree. The allusion to Job 37 isn’t compelling because it uses the language of simile: “Can you, with Him, spread out the skies, strong as a molten mirror” (Job 37:18). This doesn’t describe a literal metallic dome.

Day-Age Perspective: The separation of the water on the land from the water in the clouds suggests that the atmosphere was formed during this time. Boice writes, “The new element is the appearance of the firmament or atmosphere, what we call the sky.”[59]

Creation of the Land Perspective: Sailhamer[60] argues that God didn’t create an expanse over the entire Planet Earth. Rather, Moses is describing “the ‘clouds’ that hold the rain” in this local region. Thus, the water above the sky “is likely a reference to the clouds” in this particular area—not over the entire globe.

Young Earth Perspective: In their book The Genesis Flood (1961), John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris famously argued that the “expanse” was a “vapor canopy” over the Earth, which would account for the massive amount of water needed for the Flood, as well as for protecting humans from radiation before the Flood.

However, this is a thoroughly discredited theory. Even YECs like Jonathan Sarfati reject this view stating that it has been “rejected by most informed [Young Earth] creationists.”[61] For one, this doesn’t fit with Psalm 148:1-6 which places the waters above the heavens. Second, water does a poor job of stopping UV radiation; we can still get a sunburn on an overcast day. Third, this water canopy doesn’t explain how Noah lived for an additional ~300 years after the Flood, which would be after the supposed water canopy unloaded on the Earth in the Flood.

(1:7-8) “God made the expanse, and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so. 8 God called the expanse heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.”

Why doesn’t God call creation “good” on Day Two? This is the only day that God refrains from calling his creation “good.” One suggestion is due to the fact that God’s work on this day didn’t directly affect humans. Day Three, on the other hand, gives us land and plant life, and God calls his work “good” twice, rather than once. Another suggestion is that this day doesn’t create anything new, but is “an organization of existing material.”[62] God wouldn’t call something “good” unless he created something new.

The account in Genesis is far different from the ANE accounts. Genesis states that God merely created the sky by fiat. The Enuma Elish states that Marduk split the body of Tiamat: one part for the sky and the other for the earth:

Then the lord [Marduk] paused to view her dead body [Tiamat],

That he might divide the monster and do artful works.

He split her like a shellfish into two parts;

Half of her he set up and ceiled it as sky,

Pulled down the bar and posted guards.

He bade them to allow not her waters to escape.

Under this view, the sky is a menacing force—not a part of God’s good creation. Hamilton writes, “Sky is made not only from preexisting material but specifically from one-half of the cadaver of an evil goddess. Then Marduk must provide locks and guards to deter Tiamat from unleashing her threatening waters on the earth. Heaven as antagonist operates under restraint.”[63]

Day 3: Land and seed-bearing plant life

(1:9) “Then God said, ‘Let the waters below the heavens be gathered into one place, and let the dry land appear’; and it was so.”

Day-Age Perspective: According to geologists and geophysicists, water covered the early Earth—just as Genesis has described thus far. Volcanism and plate tectonics slowly raised the land to the surface of the Earth. This created Pangaea (from the words pan meaning “everything” and gaia meaning “earth”). This was a single continent that appeared roughly 335 million years ago. Around 175 million years ago, this single continent began to slowly break apart into the various continents we see today.

Of course, geologists state that Pangaea was preceded by older supercontinents (e.g. Columbia/Nuna, Rodinia, Pannotia, etc.). Regardless of which supercontinent came first, the point remains: The appearance of land started in “one place,” not separated into the various continents we see today. This fits well with the text of Genesis, which places the formation of a single supercontinent after the initial covering of the Earth with water.[64]

Additionally, Psalm 104—a psalm about creation—offers the same picture. It states that the “waters were standing above the mountains” (v.6). But by an act of God, the “mountains rose” out of the water covered Earth (v.8). This aligns with the imagery of Genesis, as well as the natural sciences—namely, land masses arose after water covered the early Earth.

Hugh Ross notes that most people throughout history would’ve taken for granted that land always existed on the surface of the Earth. But Genesis teaches that land came after a water-covered planet.[65] Over 4.5 billion years, the land went from 0% to 29% of the Earth’s surface. At 2 billion years, the land masses grew quickly, and then continued to grow in bursts according to geologists and geophysicists.

It’s possible that this could be another case of concordism, where we’re reading scientific findings into the text. For instance, Robert C. Newman notes that the observer may only see “one place,” but this doesn’t necessarily imply a single continent. The mention of plural “seas” (yammim) could imply more land masses and even continents.[66]

Young Earth Perspective: This view states that Pangaea was broken apart by the Flood. Antonio Snider-Pellegrini (1802-1885) may have been the first to suggest this,[67] and Sarfati calls this “certainly plausible.”[68]

Other YECs, based on 2 Peter 3:5, contend that God changed water into other chemical properties to create the continents.[69] Kulikovsky writes, “[God] caused the earth’s watery foundation to be transformed into the basic elements and compounds such as silicon and carbon.”[70] Sarfati calls this view “attractive,” but he states that the language of Genesis 1:9 could simply refer to the land being “originally covered by water.”[71]

(1:10) “God called the dry land earth, and the gathering of the waters He called seas; and God saw that it was good.”

God continues to name his creation. Once again, this shows his sovereignty and ownership over the world he is creating. Here the “earth” is not the entire Planet Earth, but only the “dry land” peeking above the water.

(1:11-13) “Then God said, ‘Let the earth sprout vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees on the earth bearing fruit after their kind with seed in them’; and it was so. 12 The earth brought forth vegetation, plants yielding seed after their kind, and trees bearing fruit with seed in them, after their kind; and God saw that it was good. 13 There was evening and there was morning, a third day.”

Theistic Evolution Perspective: God doesn’t directly create the plant life. Instead, he uses the words, “Let there be…” which implies a process. Moreover, the language of “Let the earth bring forth…” could be taken to mean that God allowed this plant life to evolve, rather than directly intervening. Kidner writes, “This language seems well suited to the hypothesis of creation by evolution.”[72] This definitely seems like a “hands off” approach from God, and this is a possible reading. However, it could also simply mean that plant life began to grow from the land at this time. After all, from where else would vegetation grow?

“Bearing fruit after their kind.” The language of “kind” does not refer to our modern taxonomy of “species,” which didn’t exist in Moses’ day. Indeed, even today there is considerable debate over the definition of a species. At the same time, this language seems to imply some sort of limitation for plant reproduction.

Progressive creationist James Boice writes that, in principle, theistic evolution “is at least a possibility.” After all, there “is no reason for the Christian to deny that one form of fish may have evolved from another form or even that one form of land animal may have evolved from a sea creature.”[73] He even points out that the Hebrew term “let” could allow for this. This language simply “does not specify a method by which God caused most things to come into being.”[74] However, he notes that the threefold use of “create” (baraʾ) in verses 1, 21, and 27 speak against a completely theistic evolutionary scenario.[75]

Day-Age Perspective: This perspective has difficulties because fruit trees didn’t appear until the late Cretaceous Period (~125 mya), which is well after the appearance of marine life in the Cambrian Era (~540 mya). Yet, the text clearly places plant life on the surface of the “earth.” Day-Age advocates respond by arguing that the Hebrew language is limited in its semantic range:

- “Sprout” (dešū) and “vegetation” (dešeʾ) are closely related: one is the verb and the other the noun. The term “vegetation” has a broad semantic range. It “appears to be the broader category, subsuming both ‘plants and trees.’”[76] It means “young, new grass, green herb, vegetation,”[77] or “vegetation, of which man sees only the upper part, grass, moss… green vegetation.”[78]

- “Plants” (ʿēśeb) is “one of four major synonyms for vegetation, verdure, herb, or grass” and refer to “non-woody tissue vegetation, rather than in the more restricted nuance of seasoning or medicinal plants.”[79] These “plants yielding seed” seem more general, than the “plants of the field” mentioned later (Gen. 2:5). The latter refers to “cultivated plants” of some kind, because they require humans to work the soil.[80] This is the same word used as “every kind of green food” for all animal life (Gen. 1:30).

- “Trees” (ʿēṣ) usually refers to “wood” or “lumber.” However, in the context of Genesis 1, it refers to “any kind of tree in God’s creation.”[81]

- “Seed” (zeraʿ) can mean literal “seed,” “semen,” or “offspring.” It can refer to the “seed” of men or animals (Jer. 31:27), as well as the “seed” of Eve or the “seed” of Satan (Gen. 3:15). These are surely metaphorical uses of the term because Satan doesn’t have literal offspring.

Day-Age proponents argue that this language simply lacks scientific precision. It could broadly refer to “green plant life” and “would apply generically to any photosynthetic land life.”[82] In other words, the plant life might not refer to robust land plants, as we know them, but rather to primitive photosynthetic life.

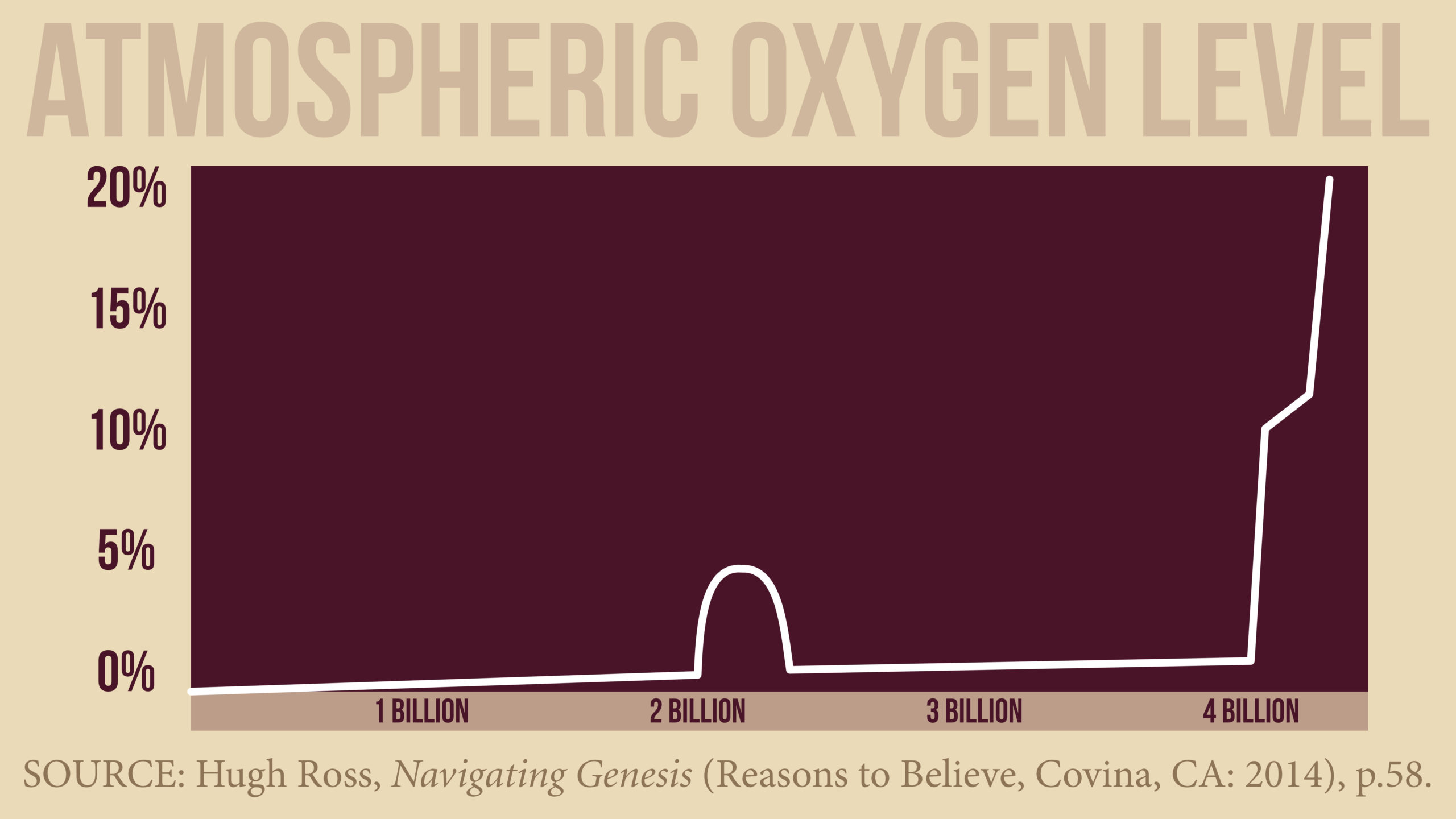

Hugh Ross argues that something had to oxygenate the atmosphere before the Cambrian Explosion (~540 mya), and this “could have been achieved only if vegetation [of some kind] had long been present on the continental landmasses.”[83] He cites two papers from the scientific journal Nature that demonstrate evidence of pre-Cambrian, non-ocean dwelling plant life.[84] He admits that not all of these structures were vegetation, but many were.

Other Old Earth proponents contend that the days might overlap or be compressed accounts. Take Day Six for example: In Genesis 1:27, we read that God created man and woman. If all we had was this text, we might assume that the man and woman were created at the same moment. However, Genesis 2 shows that there was a gap of time in between these two events (v.7, 21-22). Perhaps the creation of plant life was also separated by a gap of time. Boice writes, “The creative acts compressed into Genesis 1:11 did not necessarily take place all at one time. They could have taken place over a fairly long period in which grasses could have come first, followed by herbs, followed by fruit trees.”[85]

Intermittent-Day Perspective: From this view, God’s creation could have begun earlier, but wasn’t finished until later.[86] So, with regard to the fruit trees preceding marine life, Newman writes, “It is not necessary to suppose that the fruit trees of this passage were created before any kind of animal life. Instead, this passage simply states that the creative period involving land vegetation began before the later creative periods of the animals. In any case, since Genesis one mentions vegetation only once in the whole account, it is possible that all vegetation is mentioned together merely for economy of expression, or to indicate its significance as the foundation upon which animal life, including human life, builds.”[87]

Young Earth Perspective: Because the sun isn’t created until Day Four, God gave the plants light through his Shekinah glory. It’s also possible that God created these plants ex nihilo and they could “survive one day without sunlight.”[88] Moreover, micro-organisms were likely created on the same day.[89] Again, we find this view untenable, because plant life needs something with the same mass, heat, energy, and gravity of the sun. At this point, what is the difference between God’s Shekinah glory and God creating the sun itself?

Day 4: Sun and moon (separating day and night)

(1:14) “Then God said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years.’”

Did God create the sun, moon, and stars on Day Four? No. God had already created the “heavens and the earth” in verse 1, which includes the sun, moon, and stars (cf. Joel 3:15-16). This text assumes that these cosmic entities already existed. The Hebrew has a different syntax from verse 6, and it literally says, “Let the lights in the expanse of the sky separate.”[90] This refers to the function of these heavenly bodies—not their creation.[91]

Day-Age Perspective: According to natural history, the atmosphere was initially opaque, and the slow oxygenation of the atmosphere allowed light to pass through. According to the Day-Age view, this makes sense of light piercing through this opaque covering (Gen. 1:3). At this early stage, a light cycle would be visible, rather than casting the surface of the Earth in darkness. James Boice writes, “Light had been reaching earth since the first day of creation; it was through this influence that the vegetation created on day three was enabled to appear and prosper. But now the skies cleared sufficiently for the heavenly bodies to become visible. It is not said that these were created on the fourth day; they were created in the initial creative work of God referred to in Genesis 1:1. But now they begin to function as regulators of the day and night.”[92]

Yet because of volcanic activity and other factors, the sky would’ve still been quite hazy for billions of years. It would be comparable to a “heavy overcast of a stormy day,”[93] being translucent but not yet transparent.

On Day Four, the atmosphere changed from light-diffusing to light-transmitting,[94] and the sun and moon would’ve become clearly visible at this time.[95] This would prepare the way for God’s next progression of creation: marine and terrestrial animals. The visibility of the sun would be necessary to show them the “best times to feed, reproduce, migrate, and/or hibernate.”[96] Again, if the viewer of the account is the Spirit on the surface of the Earth (Gen. 1:2), then this would make sense.

Creation of the Land Perspective: Sailhamer states that verse 6 describes the creation of the “expanse.” However, in this passage, the Hebrew text literally states, “Let the lights in the expanse of the sky separate.”[97] This implies that the Sun already existed. He writes, “God’s command assumes that the lights were already in the expanse and that in response to his command they were given a purpose, ‘to separate the day from the night’ and ‘to mark seasons and days and years.’ …The narrative assumes that the heavenly lights have been created already ‘in the beginning.’”[98]

Intermittent-Day Perspective: Robert Newman writes that this “describes the breakup of the earth’s cloud cover as seen by an earthbound observer who witnesses the first appearance—rather than the creation—of the sun, moon, and stars now that the cloud cover breaks up.”[99] He continues, “Until the clouds had cleared enough to expose the sun, an earthbound observer would not be able to see what was producing the day/night sequence.”[100]

Young Earth Perspective: As we stated above, YECs believe that up until this point, the “light was directly created by God.”[101] They point out that God will be our cosmic light source in the New Heavens and Earth (Rev. 21:23). However, further problems surround this interpretation: First, Revelation is written in the apocalyptic genre—not a historical genre. Second, Revelation refers to the future—not to the past. Third, on this view, the Planet Earth is actually older than the Sun! We have to tip our hat to the consistency YECs, but we must simply marvel at their bizarre conclusions!

Sarfati argues that there is no problem with having days without the sun, because “God even defines a day and a night in terms of light or its absence.”[102] Yet, once again, this is unfounded when our text specifically states that the purpose of the Sun was to mark out what a day even is: “Let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years” (Gen. 1:14).

Genesis demythologizes ancient Near Eastern religions. This has an “antimythical thrust,” and perhaps in no other section “does this polemic appear so bluntly as it does here.”[103] Matthews writes, “Mesopotamian and Egyptian religions speak of their great cosmic gods of Heaven, Air, and Earth. The Sumerians have their Anu, Enlil, and Enki; the Babylonians have their trinity of stars, Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar; and Egypt has Nut, Shu, and Geb with the preeminent astral deity, the sun god Re. Genesis declares otherwise: Israel’s God rules the heavens and the earth.”[104]

(1:15-19) “‘And let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth’; and it was so. 16 God made the two great lights, the greater light to govern the day, and the lesser light to govern the night; He made the stars also. 17 God placed them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth, 18 and to govern the day and the night, and to separate the light from the darkness; and God saw that it was good. 19 There was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.”

Genesis continues to demythologize ANE cosmogonies. Moses spills a lot of ink describing the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. In the ancient Near East, these celestial bodies were worshipped as gods. In fact, they were “some of the most important gods in the pantheon” and “the stars were often credited with controlling human destiny.”[105] For instance, in the Egyptian texts, the sun and moon were deities (Re and Thoth). By contrast, Moses states that these are merely the lifeless furniture of the universe, created by the omnipotent word of the true God!

Moses uses the word “the greater light,” rather than the standard word “sun” (šemeš). The same is true with referring to the “lesser light,” rather than the word “moon” (yārēaḥ). In fact, Wenham writes, “The sun and moon are not given their usual Hebrew names… Instead they are simply called ‘the larger’ and ‘the smaller light.’”[106] We might marvel at the size and power of the sun, but God simply calls it “the larger light.” Hamilton comments, “Thus this text is a deliberate attempt to reject out of hand any apotheosizing of the luminaries, by ignoring the concrete terms and using a word that speaks of their function.”[107] In Genesis, God creates the celestial bodies. In the Enuma Elish, it “does not record the creation of these lights, for they are ‘great gods.’”[108]

Day-Age Perspective: The word “made” is pluperfect, which can be translated “had made” (cf. Gen. 31:34).[109] C. John Collins writes, “‘He made’ is not the same as ‘he created.’”[110] In his commentary on Genesis, he notes, “The verb made [‘asa] in Genesis 1:16 does not specifically mean ‘create’; it can refer to that, but it can also refer to ‘working on something that is already there’… or even ‘appointed.’”[111] This text, therefore, doesn’t tell us when God created the Sun or Moon, only why he created them.[112]

Sailhamer adds that verse 16 doesn’t refer to the initial creation of the Sun and Moon. These were already created in verse 1. Rather, the text is stating, “God [and not anyone else] made the lights and put them into the sky… God alone is the Creator of all things and worthy of the worship of his people.”[113]

Day 5: Sea life and sky life

(1:20-23) “Then God said, ‘Let the waters teem with swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth in the open expanse of the heavens.’ 21 God created the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, with which the waters swarmed after their kind, and every winged bird after its kind; and God saw that it was good. 22 God blessed them, saying, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth.’ 23 There was evening and there was morning, a fifth day.”

Did Moses believe in sea monsters? There are two plausible options. The Hebrew word for “sea monsters” (tannîm) refers to “any large reptile.”[114] It can refer to “enormous sea creatures,” but it is “often used in a figurative sense to denote God’s most powerful opponents, whether natural (Job 7:12) or national (Babylon: Jer 51:34; Egypt: Isa 51:9; Ezk 29:3; 32:2.)”[115] But it has a broad enough range of meaning that it can even include a “jackal” (Lam. 4:3). Therefore, Moses could have large marine life in mind.

Another option is that Moses is continuing to create a polemic against the ancient Near Eastern myths.[116] Moses could be alluding to a similar word (tnn) that was used in Ugaritic literature to refer to sea monsters. The prophets and psalmists referred to the “sea monsters” (tannîm) of the ancient Near East. However, they weren’t affirming their existence. Instead, they used the “mythopoetic materials only for allusion to express their affirmation in the sovereignty of God.”[117] That is, even these creatures should praise God (Ps. 148:7). Here, the great and powerful sea monster is “depicted as no more than a sea creature,” and they are “numbered with the smallest of the sea in God’s eyes.”[118] Again, the Ugaritic texts describe these creatures as being in battle with Baal. Yet, Genesis 1 “does not even hint of a battle.”[119]

“Birds” (ʿôp) has a very broad range of meaning. It literally means “flying things,”[120] including “birds or insects.”[121]

Day-Age Perspective: Proponents of this view are criticized for holding to a chronological sequence, because whales and birds existed after land animals. 95% of modern bird species appeared abruptly between 65-55 mya. Yet land animals are not created until Day Six. Boice writes that most progressive creationists allow “for some overlap of the creative days.”[122]

Hugh Ross responds by noting that these sea mammals are referred to “generically,”[123] while the land animals are given more detailed description. This could refer to the Avalon Explosion and the Cambrian Explosion (530-520 mya),[124] both of which preceded land animals.[125] Regarding the land animals of Day Six, he writes, “The specificity of this list suggests that it is not referring to land mammals generically. A closer look suggests it focuses, rather, on three categories of land mammals strategically important for the support of humans.”[126] The history of life on Earth could fit with this view:

Odontode Explosion (425-415 mya). During this ten million year period, jawed fish with teeth appear in the fossil record abruptly. Arthur Strahler (geoscientist from Columbia University) writes, “This is one count in the creationists’ charge that can only evoke in unison from paleontologists a plea of nolo contendere [no contest].”[127]

Devonian Nekton Revolution (410-400 mya). Before this event, marine ecosystems were filled with plankton and bottom dwelling marine life. In this period, swimming marine life with jaws appeared.

Carboniferous Insect Explosion (318-300 mya). During this eighteen million year period, winged insect groups appear suddenly without precursors in the earlier strata. These include dragonflies, roaches, bugs, wasps, and beetles.

Triassic Explosion (~252 mya). Many new orders and families of marine invertebrates, insects, and tetrapods appear after a mass extinction. Peter D. Ward compares this to the Cambrian Explosion—only for animal life on land.[128]

Early Triassic Terrestrial Tetrapod Radiation (251-240 mya). In eleven million years, the first dinosaurs, turtles, lizard-relatives, crocodile relatives, and mammal-like animals appear. There are no known precursors for any of these—except the crocodile relatives and mammal-like animals.[129]

Radiation of Modern Placental Mammals (62-49 mya). These appear without any discernible precursors.[130] These include the orders that would include bears, bats, and horses. Jeffrey Schwartz (biologist at the University of Pittsburgh) writes, “We are still in the dark about the origin of most major groups of organisms. They appear in the fossil record as Athena did from the head of Zeus—full-blown and raring to go, in contradiction to Darwin’s depiction of evolution as resulting from the gradual accumulation of countless infinitesimally minute variations.”[131]

To summarize, Progressive Creationists would argue that the text is referring to generic avian and marine life on Day Five, and it simply omits earlier land animals on Day Six. Instead, the text focuses on domestic animals on Day Six. Of course, we know that Genesis is not an exhaustive account. While the text states that God created “every living creature that moves” (Gen. 1:21), this is surely only referring to this time period, because Genesis goes on to describe more creatures in the subsequent verses.

Day 6: Animals and humans

(1:24-25) “Then God said, ‘Let the earth bring forth living creatures after their kind: cattle and creeping things and beasts of the earth after their kind’; and it was so. 25 God made the beasts of the earth after their kind, and the cattle after their kind, and everything that creeps on the ground after its kind; and God saw that it was good.”

Theistic Evolution Perspective: As we noted above (Gen. 1:11-12), the Earth brought forth plant life, and some TE proponents see that this language could account for an evolutionary process (“Let the earth bring forth living creatures”). This is possible. However, the following verse seems to imply some sort of divine intervention (“God made the beasts of the earth”). The term “made” (ʿāśâ) is often used of God’s miraculous intervention (Deut. 29:2-3; Josh 23:3; 24:17; 1 Kin. 8:39; Ps. 98:1; Isa. 25:1).

Young Earth Perspective: God created the rest of the animal kingdom, including dinosaurs on Day Six. They argue that this fits the description of the Behemoth in Job 40. Sarfati points out that the “the discovery of blood cells, blood vessels, proteins, and DNA in dinosaur bones” could “not have survived 65 million years.”[132] He continues, “The Bible shows that this carnivory must be post-Fall,” and these animals were “vegetarian at that time.”[133]

(1:26-27) “Then God said, ‘Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.’ 27 God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.”

Finally, we reach the creation of humans. The poetic parallelism in verse 27 “sets this verse apart as the climax of the narrative.”[134] God speaks to himself in this passage, which also adds to the majestic creation of mankind.

“Let Us… Our image… Our likeness.” Does this passage support the doctrine of the Trinity? (see Genesis 1:26)

“Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness.” What does it mean to be made in the image of God? See our article, “Humans Bear the Image of God.”

The text uses somewhat “hands off” language for the other life forms (“Let there be…” or “Let the earth bring forth…). But this changes drastically with regard to humans. Here, we read, “Let Us make…” and “God created man…” This implies special creation.

“Make” (ʿāśâ) is a somewhat generic term for creation. It sometimes refers to God’s supernatural intervention (Josh. 24:17; Ps. 98:1; Isa. 25:1). However, it simply refers to “the act of fashioning the objects involved in the whole creative process.”[135]

“Created” (bārāʾ) primarily emphasizes “the initiation of the object” and “always connotes what only God can do and frequently emphasizes the absolute newness of the object created.” The use of this term carries the implication that “the physical phenomena came into existence at that time and had no previous existence in the form in which they were created by divine fiat.”[136] In this specific Qal form, the word is only used of God’s activity, and it is a “purely theological term.” Consequently, the use of this term is “especially appropriate to the concept of creation by divine fiat… Since the word never occurs with the object of the material, and since the primary emphasis of the word is on the newness of the created object, the word lends itself well to the concept of creation ex nihilo although that concept is not necessarily inherent within the meaning of the word.”[137]

“Formed” (yāṣar) occurs in chapter 2 to refer to creation of the first human (Gen. 2:7). This word is often used as synonymous with “make” (ʿāśâ) and “created” (bārāʾ). However, the term refers to the “shaping or forming of the object involved.”[138] This term isn’t contradictory with the earlier terms. God seems to have created the first human de novo, and he later shaped and formed him as his designer and creator.

“Male and female.” Hamilton writes, “Unlike animals, man is not broken down into species (i.e., ‘according to their kinds’ or ‘all kinds of’), but rather is designated by sexuality: male and female he created them. Sexuality is applied to animal creatures, but not in the Creation story, only later in the Flood narrative (6:19).”[139]

(1:28) “God blessed them; and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over every living thing that moves on the earth.’”

The word “subdue” (kābaš—kawbash) means “to bring into bondage, keep under, force.”[140] Sometimes the word is used for an immoral force (Est. 7:8; Jer. 34:11, 16), but other times it is used for moral force or loving leadership. For example, Micah writes, “You will again have compassion on us; you will tread (kābaš) our sins underfoot and hurl all our iniquities into the depths of the sea” (Mic. 7:19 NIV). In this example, God is exercising force to have “compassion” and remove their sins.

Which understanding better fits the context of Genesis 1:28? Since this is before the Fall, loving leadership is surely in view. The first humans were told to rule and reign over creation—not to exploit creation. As image-bearers of God, we are to care for God’s creation in the same way that he created it, knowing that we are stewards of his creation.

God himself not only cared for the people of Ninevah, but also for their “many animals” (Jon. 4:11). Solomon writes, “A righteous man cares for the needs of his animal” (Prov. 12:10). And finally, at the end of human history, one criterion of judgment will be how people treated the Earth. John writes, “The time came for the dead to be judged… to destroy those who destroy the earth” (Rev. 11:18).

Genesis continues to contrast with the ANE myths. The Enuma Elish states that the god Marduk created humans out of the blood of the dead god, Kingu. And Marduk did this to have a race of slaves to serve the gods:

They bound him (Kingu), held him before Ea

inflicted the penalty on him,

severed his arteries;

and from his blood he formed mankind

imposed toil on man, set the gods free

These creation accounts are diametrically opposed to one another. Hamilton comments, “Man is created as an afterthought, and when he is created he is predestined to be a servant of the gods. There is nothing of the regal and the noble about him such as we find in Gen. 1. Basically he is a substitute, one who is created from the blood of a rebellious deity. The anthropologies of Gen. 1 and Enuma elish could not be wider apart.”[141]

Gap Theory Perspective: Critics of the gap theory argue that the word “fill” (mālēʾ maw-lay) would need to be rendered “refill” the Earth. Yet, gap theorists respond by noting that the same term “fill” is used after the Flood, where God says, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth.” The term simply refers to filling at the present moment, having nothing to do with the past (cf. Gen. 17:2, 28:3; 35:11; 48:4; 47:27).

(1:29-30) “Then God said, ‘Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is on the surface of all the earth, and every tree which has fruit yielding seed; it shall be food for you; 30 and to every beast of the earth and to every bird of the sky and to every thing that moves on the earth which has life, I have given every green plant for food’; and it was so.”

Genesis continues to stand in sharp contrast to the ancient Near Eastern deities and creation accounts. Wenham writes, “God’s provision of food for newly created man stands in sharp contrast to Mesopotamian views which held that man was created to supply the gods with food.”[142] In the OT, God doesn’t need our food! Elsewhere, God says, “If I were hungry I would not tell you, for the world is Mine, and all it contains. 13 Shall I eat the flesh of bulls or drink the blood of male goats?” (Ps. 50:12-13)

Young Earth Perspective: YECs argue that animal death did not occur until after the Fall. Therefore, even carnivores (by today’s standards) were vegetarians. Sarfati writes, “The Fall is the big discontinuity of earth history, and that’s where animal carnivory could have begun. Certainly, by the time of the Flood, there was animal carnivory.”[143] They connect this with Isaiah 11:6-9 and 65:25, claiming that these passages make an “Edenic connection.”[144] But can we honestly believe that the teeth of the Tyrannosaurus Rex were designed for eating leaves?

Old Earth Perspective: OECs note that God did give plant life for food. However, this doesn’t teach that animals could only eat vegetables. To assert this would commit the “negative inference fallacy.”[145] That is, just because God gave plant life for food, this does not imply that this was the only food given.

At most, this would only apply to land animals—not marine life. God gave this command to “every thing that moves on the earth” (Gen. 1:30). To expand this text to refer to all life is simply not in view.[146] Collins writes, “There’s no indication of a change in diet for animals anywhere in the Bible; and though we might argue that man wasn’t to eat meat until after the flood (Gen. 9:3), we still can’t say what other animals ate.”[147] That is, God never lifted this dietary restriction for animals—only humans.[148] This implies that animals were eating meat in addition to vegetables the entire time, including up to the present moment.

Hugh Ross notes that green plants are the “foundation for the food chain.”[149] So, even carnivores depend on green plants for food—either directly or indirectly. Kidner agrees when he writes, “It is a generalization, that directly or indirectly all life depends on vegetation, and the concern of the verse is to show that all are fed from God’s hand.”[150]

Finally, Psalm 104 is held to be a psalm about creation, and it doesn’t describe animal death as evil or sinful. In fact, we read, “The young lions roar after their prey and seek their food from God” (Ps. 104:21). The psalmist sees no problem with this, and in fact, he praises God for his creation (Ps. 104:24). The only beings who are called “wicked” or “sinners” are humans—not animals (Ps. 104:35).

(1:31) “God saw all that He had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.”

Repeatedly throughout this chapter, God called his creation good. Here he concludes by calling it “very good.” How could God call his creation “very good” if it included animal death, carnivory, and predation? If Sailhamer is correct, the word “good” (ṭôḇ) doesn’t refer to moral or philosophical goodness, but simply refers to being “beneficial for man.” See comments on verse 4.

Day 7: God’s rest

(2:1) “Thus the heavens and the earth were completed, and all their hosts.”

The creation account of Genesis 1 refers to “the heavens and the earth,” not just the Garden of Eden. This is an inclusio that bookends Genesis 1:1.

“All their hosts” refers to the stars (cf. Deut. 4:19).[151]

(2:2-3) “By the seventh day God completed His work which He had done, and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had done. 3 Then God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made.”

Why does God “rest” on the seventh day? The text says that God rested, but it doesn’t say that he needed to rest. God didn’t rest because he was tired, but because he was finished. This is similar to a musician who writes a “rest” between measures.[152] She would rest because it was part of her masterpiece—not because she was tired. The term “rested” (šābat) literally means “the cessation of creative activity.”[153] Incidentally, after humanity came about, no new species have arrived on Earth. God rested or “ceased” from his creative activity.

Day-Age Perspective: These proponents note the conspicuous absence of the language “there was evening and there was morning.” If this language is so crucial to warrant a literal 24-hour day, then why doesn’t it appear on Day Seven? The Bible teaches that God has continued to rest to this very day (Ps. 95:7-11; Jn. 5:16-18; Heb. 4:1-11). This adds further support to the concept that the days of Genesis were not 24-hours, but long ages of time. Ross writes, “Jesus’ appeal is that He is honoring the Sabbath the same way His Father does. That is, His Father works ‘to this very day’ even though ‘this very day’ is part of His Sabbath rest. God—both the Son and Father—honors His Sabbath by ceasing from creation work. God’s Sabbath (seventh creation day) does not preclude His healing people any more than it precludes a man from changing his baby’s diaper on Sunday.”[154]

Young Earth Perspective: Despite the fact that the “evening and morning” language is conspicuously absent, Sarfati persists in referring to this as a “regular solar day.”[155] He states that “God’s creation work was completed… God is still working, but he is not creating, in the Genesis 1 sense of the word.”[156]

Questions for Reflection

When Moses wrote this, what do you think his original audience thought the main message was about this chapter? (Consider the fact that they had just left the polytheism of Egypt, the worship of Pharaoh, and the horrors of slavery.)

How firm should we be in our interpretation of Genesis 1?

What are some of the boundaries we should firmly hold to? What are some areas of disagreement that we might have that aren’t as important?

What does this chapter of Scripture tell us about God? What does it tell us about his method of creation?

[1] Henri Blocher, In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1984), p.62.

[2] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.28.

[3] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing Company, 2006), p.42.

[4] Gary D. Pratico and Miles V. Van Pelt, Basics of Biblical Hebrew Grammar (Zondervan, 2009), p.192.

[5] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.28.

[6] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 106.

[7] C. John Collins, Did Adam and Eve Really Exist? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2011), p.156.

[8] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 14.

[9] Vern Poythress, Interpreting Eden (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), p.144.

[10] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p. 58.

Henri Blocher, In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1984), p.63.

[11] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.28.

[12] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 140, 142.

[13] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 129.

[14] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.59.

[15] Emphasis mine. Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), p.15.

See also Vern Poythress, Interpreting Eden (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), p.145.

[16] Hugh Ross, The Genesis Question (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 1998), p.20.

[17] Derek Kidner, Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.47.

[18] John C. Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), p.115.

[19] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 20.

[20] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 137.

[21] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 131.

[22] Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 2001), p.60.

[23] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 25.

[24] Alexander Heidel, The Babylonian Genesis: The Story of Creation (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 98-101).

[25] K.A. Kitchen, Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago IL: InterVarsity Press, 1966), pp.89-90.

[26] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 134.

[27] K.A. Kitchen, Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago IL: InterVarsity Press, 1966), pp.89-90.

[28] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 111.

[29] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 134.

[30] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 135-136.

[31] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing Company, 2006), p.51.

[32] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.31.

[33] John C. Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), p.172.

[34] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 25.

[35] Robert C. Newman, Perry G. Phillips, Herman J. Eckelmann, Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed. Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute, 2007), p.63.

[36] John D. Currid, A Study Commentary on Genesis: Genesis 1:1-25:18, vol. 1, EP Study Commentary (Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, n.d.), 61.

[37] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.39.

[38] Emphasis mine. John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 26.

[39] David Snoke, A Biblical Case for an Old Earth (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2006), p.139.

[40] John D. Currid, A Study Commentary on Genesis: Genesis 1:1-25:18, vol. 1, EP Study Commentary (Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, n.d.), 61.

[41] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 3252.

[42] Hugh Ross, A Matter of Days (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2004), pp.77-78.

[43] K. A. Mathews, Genesis 1-11:26, vol. 1A, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 146.

[44] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 26.

[45] Emphasis mine. Derek Kidner, Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.51.

[46] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), p.19.

[47] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 3397.

[48] The most influential person to espouse this view was the Jewish biblical scholar Nahum Sarna (1923-2005).

[49] Currid makes this outrageous claim regarding the firmament: “it actually should be taken at face value to mean ‘a large body of water, a sea, above a solid firmament, which firmament serves as a roof to the universe and under which firmament are the sun, moon and stars’.” John D. Currid, A Study Commentary on Genesis: Genesis 1:1-25:18, vol. 1, EP Study Commentary (Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, n.d.), 66.

[50] J.B. Payne, 2217 רָקַע. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 861.

[51] H.J. Austel, 2407 שׁמה. John N. Oswalt, “310 גָּבַר,” ed. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 935.

[52] G.L. Carr, John N. Oswalt, “310 גָּבַר,” ed. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 666.

[53] Robert C. Newman, Perry G. Phillips, Herman J. Eckelmann, Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed. Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute, 2007), p.66.

[54] Robert C. Newman, Perry G. Phillips, Herman J. Eckelmann, Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed. Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute, 2007), p.66.

[55] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 29.

[56] See Vern Poythress, Interpreting Eden (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), pp.176-178.

[57] Vern Poythress, Interpreting Eden (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), p.179.

[58] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.45.

[59] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.74.

[60] John H. Sailhamer, “Genesis,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 28, 29.

[61] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 4563.

[62] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 20.

[63] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 123.

[64] Hugh Ross, The Genesis Question (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 1998), p.27.

[65] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.47.

[66] Robert C. Newman, Perry G. Phillips, Herman J. Eckelmann, Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed. Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute, 2007), p.68.

[67] Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, Le Création et ses Mystères Devoilés (The Creation and its Mysteries Unveiled), Franck and Dentu, Paris, 1858.

[68] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 4779.

[69] Russell Humphreys, The Creation of Planetary Magnetic Fields, CRSQ 21(3):140-149, 1984.

[70] A.S. Kulikovsky, Creation, Fall, Restoration (2009), p. 133.

[71] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 4796.

[72] Derek Kidner, Genesis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.52.

[73] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.50.

[74] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.50.

[75] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.50.

[76] R. B. Allen, 1707 עשׂב R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 700.

[77] R. B. Allen, 1707 עשׂב. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 700.

[78] Koehler, L., Baumgartner, W., Richardson, M. E. J., & Stamm, J. J. (1994-2000). The Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 234). Leiden: E.J. Brill.

[79] R. B. Allen, 1707 עשׂב. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 700.

[80] R. B. Allen, 1707 עשׂב. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 700.

[81] R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 689.

[82] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), pp.49-50.

[83] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.51.

[84] L. Paul Knauth and Martin J. Kennedy, “The Late-Precambrian Greening of the Earth,” Nature 460 (August 6, 2009): 728-732.

Paul K. Strother (et al.), “Earth’s Earliest Non-Marine Eukaryotes,” Nature 473 (May 26, 2011): 505-509.

[85] James M. Boice, Genesis: An Expositional Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p.75.

[86] J. Oliver Buswell, Jr., A Systematic Theology of the Christian Religion (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1962), vol. 1, pp. 144-145.

[87] Robert C. Newman, Perry G. Phillips, Herman J. Eckelmann, Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed. Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute, 2007), p.68.

[88] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 4876.

[89] Jonathan Sarfati, The Genesis Account (Powder Springs, GA: Creation Book Publishers, 2015), Kindle loc. 4930.