I can still remember the first time I heard of William Lane Craig. One of my roommates brought home a VHS tape of Craig’s debate with atheist Frank Zindler. (For younger readers, “VHS” was a way primitive cultures watched movies in the previous millennium.) In a gracious and articulate way, Craig offered sophisticated and sound arguments for Christian theism, and it quickly became clear that Zindler did not realize whom he had shown up to debate. At various points, Zindler honestly looked more dazed and confused than Gary Busey competing in Celebrity Jeopardy…

I can still remember the first time I heard of William Lane Craig. One of my roommates brought home a VHS tape of Craig’s debate with atheist Frank Zindler. (For younger readers, “VHS” was a way primitive cultures watched movies in the previous millennium.) In a gracious and articulate way, Craig offered sophisticated and sound arguments for Christian theism, and it quickly became clear that Zindler did not realize whom he had shown up to debate. At various points, Zindler honestly looked more dazed and confused than Gary Busey competing in Celebrity Jeopardy…

Afterward, I avidly began to read Craig’s writing, I listened to every one of his podcasts (no exaggeration!), and I watched virtually all of his debates (also no exaggeration!). I don’t know of a Christian scholar who has influenced me more than William Lane Craig. His intellectual impact leaves me deeply indebted, and I still consider him to be the greatest living intellectual defender of Christianity in the public square.

It is in this spirit that I must voice my deep disagreement with Craig’s recent conclusions regarding the opening chapters of Genesis. Craig has defined Genesis 1-11 as being in the genre of mytho-history. I find this to be seriously mistaken, and contend that this view will have a massive impact on the church, and not for the good.

Areas of Agreement and Disagreement

To begin, there is much upon which we agree. For one, Craig affirms that Adam and Eve were real, historical persons,[1] and he holds that Adam and Eve were the sole progenitors of the human race. It has become popular to deny these key biblical teachings; yet Craig affirms both, and I commend him for it.[2]

And yet, Craig understands Genesis 1-11 to be in a genre called “mytho-history.” I reject his genre analysis. But before I commit to arguing against this assessment, I hope to accurately articulate it. As one person has said, “A problem well defined is half-solved.”

What is a Myth?

Modern people typically use the term “myth” to refer to something that is false or fabricated (e.g. “Myth Busters” or “The Myth of the American Dream” or “The Myth of Capitalism/Socialism/Marxism”). However, to be very clear, this is not the way Craig defines this term. Instead, he appeals to the late Alan Dundes—a folklorist from the University of California, Berkeley—to define the term “myth.” He offers three different types, opting for the third usage.[3]

(1) Folktales are prose narratives that are understood to be fictitious. They often contain talking animals, they are set in any time and place, and they are definitely not grounded in history (e.g. “Little Red Riding Hood” or “Hansel and Gretel”).

(2) Legends are prose narratives that exist in the world that is similar to ours. They are often secular and not religious accounts. These stories take place in our world, but they are only loosely based on any real historical events (e.g. “Robin Hood”).

(3) Myths, by contrast, should “not be synonymous with falsehood.” Rather, a myth has several key components. First, it is a linguistic composition—either oral or written. Second, it is a sacred narrative that has religious significance and speaks of God or the gods. Third, it is traditional and old—not a recent composition. Fourth, it “seeks to explain present realities by anchoring them in the past,” which is “understood to mean the pre-historical past.” This final criterion is called an “etiology.”

To summarize succinctly, Craig defines myths as “sacred narratives which seek to explain how the world and man came to be in their present form.”[4]

Assessment

These criteria are so broad that we could drive a Mack truck through them. Consider each criterion below: (Dr. Craig replied to my analysis on a recent podcast. You may see his response here. I have included edits to my original article that make it clear that I am referring to ancient creation narratives, which is the cultural and historical context for Genesis 1-11. I have added these in a bold font in this section below.)

First, a myth is a linguistic composition. (This literally applies to all religious literature.) EDIT: An exception would be oral tradition that is later codified. Yet, even in this case, it would be a linguistic composition.

Second, it is a sacred narrative to the community. (Again, this describes all religious writings.) EDIT: This would be true of nearly all ancient creation narratives.

Third, myths are traditional and old. (Again, this would apply to virtually all religious texts with the exception of Mormonism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Scientology, etc.).

Fourth, these sacred narratives seek to explain how the world and man came to be in their present form. (Not to be a broken record, but again, this refers to nearly all religious literature.) EDIT: Again, this would be true of most ancient creation narratives, as I demonstrate in an earlier article, “Did Genesis Borrow the Creation and Flood from Mesopotamian Myths?”

There is nothing problematic with these criteria; rather, these criteria have the problem of saying nothing. This definition of “myth” would rule out everyday fiction and fantasy like Star Wars and Superman, but beyond this, these criteria give little guidance in analyzing the genre of Genesis.

What is Mytho-History?

Craig is clear that mytho-history doesn’t refer to falsehood. In an interview, he stated, “Nobody is saying that Genesis is fiction. At least, I’m not!”[5] However, in all honesty, it is quite difficult to nail down precisely what Craig means by mytho-history.

“Genesis 1-11 are plausibly to be understood as Hebrew myths with an interest in history.”[6]

“I would say the ‘mytho’ part applies primarily to the stories—the narratives. And then the genealogies serve to order these historically and I think show that these are taken as being about real people and real things that happened. Though even the genealogies… can’t be pressed for a kind of wooden literalness.”[7]

“This is a type of literature that is not meant to be read as a literal, historical account.”[8]

“[Mytho-history] is intended to describe historical persons and events that actually took place, but these events are cloaked with the language of mythology and metaphor—and therefore, should not be pressed for literal accuracy.”[9]

Am I the only one confused by these statements? I’ve seen more clarity in assembly instructions for Ikea furniture. In attempting to clarify the genre, these statements actually seem to make this view even more disorienting.

Craig states that he first heard about mytho-history from Bill T. Arnold (a professor of OT at Asbury Seminary). Indeed, Arnold argues that we should see Genesis in the same genre as other creation and flood narratives from the ancient Near East. Here are a few of his reasons why:

First, both Genesis and other ANE texts address similar themes (e.g. creation, fall, flood, redemption, etc.). Arnold writes, “Those themes themselves are the same ones explored elsewhere in the ancient Near East in mythological literature…. The Primeval History narrates those themes in a way that transforms their meaning and import, and for these reasons we may think of these chapters as a unique literary category, which some have termed ‘mytho-historical.’”[10] Arnold holds that the “mythmaking” of the ancient Near East was “transformed in the Genesis narrative account.”[11]

Second, both texts have a linear progression. Arnold states, “Mythical themes have been arranged in a forward-moving, linear progression, in what may be considered a historicizing literary form, using genealogies especially, to make history out of myth.”[12]

Third, both accounts contain stories that have an effect on the larger narrative. That is, we don’t have a constellation of independent stories in these accounts. Rather, we have a linear, cause-and-effect storyline, where the events impact one another. Arnold notes that Genesis is history, because it “arranges themes along a time continuum using cause and effect,” and it uses “historical narrative as the literary medium for communication.”[13]

Fourth, both contain genealogies as the “backbone” of the narratives, tying the stories together. This means that the historical genealogies serve to connect the narratives as a historical account.

Assessment

As we saw above, Craig began with an incredibly broad definition of “myth.” Here, he adds confusion to chaos by adding the term “history” into the mix. He states that Genesis 1-11 have “an interest in history.” We honestly aren’t trying to be obtuse, but what exactly does he mean by this? To what extent is Genesis interested in history?

Craig explains that the genealogies are historical, while the narratives are mythical. By this, he means that the narratives of Genesis are highly “figurative” and “metaphorical,” and are not a “literal, historical account.” While the myths are about “real people and real things,” they “should not be pressed for literal accuracy.” In fact, even the genealogies shouldn’t be “pressed for a kind of wooden literalness.”[14]

This effectively allows the interpreter to treat the text with the same flexibility as a warm bowl of Silly Putty. That is, his criteria offer no concrete boundaries for identifying which events are true or false; literal or metaphorical; religious revelation or spurious speculation. To be clear, Craig understands Genesis to be non-fiction. But practically speaking, he gives no criteria for adjudicating which parts are “figurative” and “metaphorical,” and which have “literal accuracy.” Hence, Craig candidly admits,

“It’s probably futile to try to discern to what extent the narratives are to be taken literally—to identify which parts are figurative and which parts are historical…. Did a serpent speak in the Garden? Was the first woman made from Adam’s rib? Was there a worldwide flood? I see no reason to think that the viability of a genre analysis of Genesis 1-11 as mytho-history should depend upon or imply the ability to answer such questions. The author simply doesn’t draw such clear lines of distinction for us.”[15]

Take a minute to process that statement. This gives me confidence that I’m interpreting Craig accurately: his criteria are cryptic because the view itself is vague. Surely such a view offers little to no hermeneutical restraint for the interpreter to exposit the opening chapters of Genesis.

Now, I’m not a prophet or the son of a prophet (though I do work for a non-profit organization…), but I’d like to make a prediction: Those who sow to this misguided genre analysis will reap the consequences. Such a view isn’t a slippery slope; it’s is a slip and slide. It gives the interpreter no boundaries for handling these key chapters of Scripture.

Reasons for Accepting Genesis as Mytho-History

So far, we have simply defined mytho-history and described the consequences of holding to it. But perhaps he’s right. What if there truly are good reasons for accepting Genesis as mytho-history? Indeed, what justification does Craig give for understanding Genesis in this way? In our understanding, Craig gives three central reasons for adopting the mytho-history genre:

REASON #1. Genesis shares themes with other ancient Near Eastern accounts, which implies a similar genre

Thorkild Jacobsen (a renowned Assyriologist and historian of the ancient Near East) was the first to elucidate the genre of mytho-history, and Craig relies heavily on his work.[16] Jacobsen performed a critical comparison of the Eridu Genesis (the Sumerian creation account) alongside the biblical Genesis (the Hebrew creation account). As a result, Jacobsen identified key similarities, leading him to believe that these shared a similar genre.

For one, both accounts share similar themes. The Sumerian text records (1) the creation of humans, (2) the formation of kingship, (3) the construction of cities, and (4) the great Flood. Jacobsen argued that Genesis followed this same thematic arrangement.

Second, both accounts contain a chronological sequence of cause and effect. Jacobsen wrote, “This arrangement along a line of time as cause and effect is striking, for it is very much the way a historian arranges his data, and since the data here are mythological we may assign both traditions to a new and separate genre as mytho-historical accounts.”[17]

Third, both accounts contain historical genealogies. The Sumerian account has a king list, and the Hebrew account has the ancestry from Adam to Abraham. Because the Eridu Genesis has an “interest in numbers of years” for the kings, this implies a style of “chronicles and historiography.”[18] The interest in these numbers of years is unique to mythical literature, which implies a historical component. Additionally, the Sumerian and Hebrew accounts both contain long lifespans in their genealogies—also implying a similar genre.

Assessment

These superficial similarities seem to be an insufficient justification for a shared literary genre for a number of reasons.

First, our general knowledge of the ancient Near East is incredibly sparse. To understand this era, we need to traverse over 3,000 years of history to enter into an alien cultural, philosophical, and religious milieu. This is feasible to some degree, but confident assertions should be met with considerable caution. Even experts in ancient Near Eastern studies admit how underdeveloped our knowledge is. For instance, Gordon Wenham writes, “Despite the vast number of tablets unearthed and read by Assyriologists, Hittitologists, and Egyptologists, our knowledge of ancient beliefs is patchy.”[19] Even Bill Arnold writes, “In the case of Genesis we are left with even less evidence from the ancient Near East than usual when studying the Old Testament and its parallels with the surrounding environment…. It is naive to think that we are capable of reconstructing what actually happened in the history of early Israel, especially in the period of Israel’s ancestors, or even more especially the beginnings of world history.”[20] It’s odd that we would have skepticism of the historical events in Genesis, but have confidence in the genre analysis—a very nuanced and complicated.

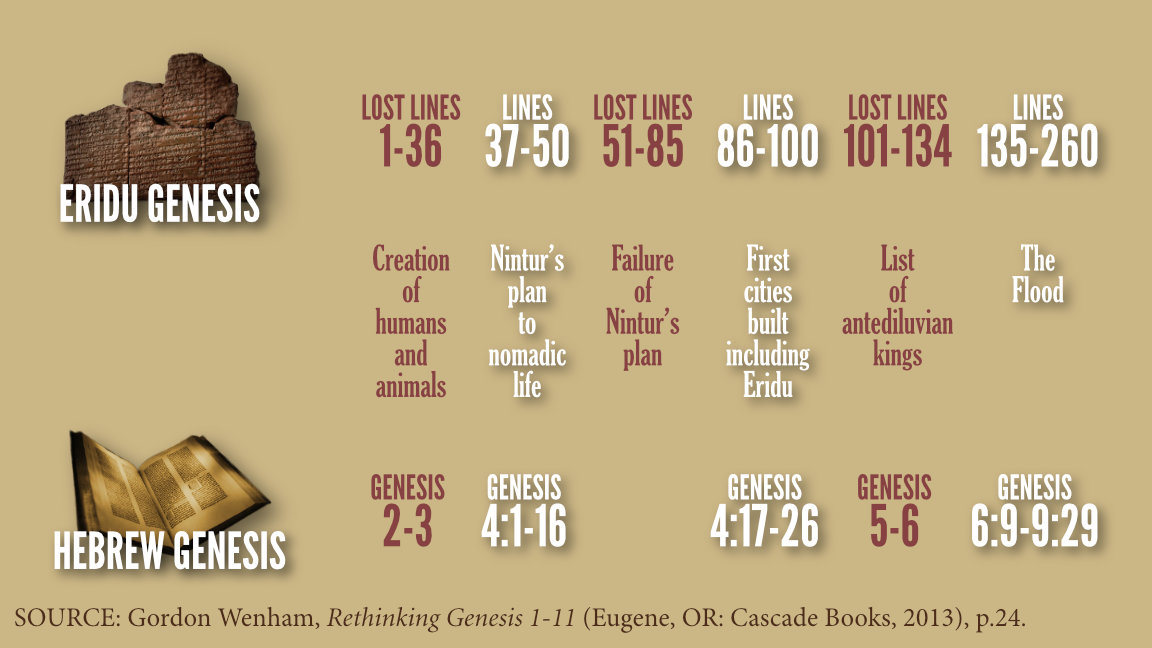

Second, the Eridu Genesis is fragmentary. While Jacobsen believed he could reconstruct this ancient text with “a fair degree of confidence,”[21] this entire account exists within a single fragmentary tablet. Gordon J. Wenham shows the reconstruction in his book Rethinking Genesis 1-11.[22] (Look at how much is lost from the original document.)

According to Wenham’s chart, 105 out of the 260 lines of the Eridu Genesis are lost. Can we honestly form a plausible comparison when 40% of the original text has rotted in the ash heap of history?

Third, the Eridu Genesis contains key differences with the biblical Genesis. For one, Genesis begins in the paradise of the Garden, while according to the Sumerian view, “Man’s original state was far from paradisial.”[23] Second, Genesis teaches that nomadism was due to Cain’s sin (Gen. 4), but the Sumerian account held that nomadism was “intrinsic to creation.” Third, the Genesis Flood was due to immorality and evil, while the Sumerian flood was (probably) caused by the excess of noise from humans. Fourth, the Eridu Genesis has an “optimistic view of existence” and “it believes in progress.”[24] In fact, the story goes from bad to better. But “in the biblical account it is the other way around. Things began as perfect from God’s hand and grew then steadily worse through man’s sinfulness [until the Flood].”[25] Fifth, the Eridu Genesis focuses on the kings—not religious figures.[26] We can articulate these differences below:

Genesis |

Eridu Genesis |

| Monotheistic |

Polytheistic |

|

Humans begin in paradise |

Humans begin in nomadism

(The earlier section is lost) |

| Nomadism due to sin |

Nomadism was a normal part of creation |

|

All humans are made in God’s image |

Focus on the institution of kingship |

| The Flood was because of sin and evil |

The Flood was because of noise and disruption |

|

Humans fall into a broken world |

Humans begin in a broken world |

| Human lifespans reach hundreds of years |

Human lifespans reach tens of thousands of years. (Just eight of the pre-flood kings rule for 241,000 years.) |

In other words, superficial similarities exist in the style and structure; yet the core content is contradictory. We find this evidence to be simply sparse. Needless to say, the case for the mytho-historical genre is not off to a good start.

REASON #2. Genesis 1-11 contain etiologies, which support the mytho-historical genre

Craig argues that etiologies in Genesis support the genre of mytho-history.

What is an etiology? The term etiology (or aetiology) comes from the Greek word aitia, which means “cause” or “reason.” Thus, etiologies are a “study of causes,” explaining “why things are the way they are now.”[27]

One primary example of an etiology is the first marriage described in Genesis 2. God forms Eve from Adam’s rib, and then Adam states that Eve is “bone of my bones” and “flesh of my flesh.” Then we read, “For this reason a man shall leave his father and his mother, and be joined to his wife; and they shall become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24).

Do you see the etiology here? Genesis 2 explains the “cause” or “reason” for marriage—a common social and religious institution in Israel. The reason is rooted in the fact that humans were created from “one flesh,” and they return to “one flesh” in marriage. Hence, the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib is an etiology for the union of marriage. We find other etiologies in Genesis:

- God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh (Gen. 2:2-3), and this is an etiology that explains why the Hebrews worked for six days and rested on the Sabbath (Ex. 20:8-11).

- Genesis 3 explains why “snakes are unpleasant and are frequent enemies of humans.”[28]

- God’s punishment for the Serpent (Gen. 3:14) is an etiology for “why serpents crawl on the ground”[29] and slither with a new “serpentine locomotion.”[30]

- Women experience pain in childbirth due to the Fall (Gen. 3:16), and people sweat and toil in their work also because of the Fall (Gen. 3:17-19).[31]

- The rainbow appears to remind us that God will never again flood the earth.[32]

- Humans speak different languages because of the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11).[33] This could be etiological for Babylon as well.[34]

Critical scholars such as Albrecht Alt,[35] Hermann Gunkel,[36] and Martin Noth[37] appealed to etiologies as a basis for dehistoricizing Genesis. Under this view, these (mythological) stories in Genesis serve to explain present realities or religious practices, but they are not rooted in real, historical events.

Assessment

Do etiologies imply a mytho-historical genre? Not at all. We find this perspective to be reductionistic at best and erroneous at worst.

For one, etiologies do not dehistoricize the events in question. Instead, etiologies could explain present reality because they actually occurred in the past. After all, in the sciences, etiologies refer to the causes behind medical conditions (e.g. “You have lung cancer because you smoked cigarettes”).

C. John Collins argues that etiologies “might actually give the true origin of some feature of contemporary life,” and he states that “calling it ‘etiological’ settles no questions at all.”[38] The “etiological motive cannot be said to undermine the fundamental historicity of the tale.”[39] OT scholar James Hoffmeier explains,

Etiologies, however, are not necessarily fictitious accounts. [They are descriptive] and may or may not be historical… Etiology, then, speaks more to the function of the story than its literary form.[40]

Regarding the critical idea that etiologies dehistoricize events, John Bright explains, “Nothing is more fundamentally wrong in the method of Alt and Noth than this.”[41] After all, Bright argues, it isn’t clear as to whether these etiologies are the cause or the effect of the current cultural institution.

Consider the Passover: Did the slaying of an innocent lamb lead to the annual celebration of the Passover, or did the people invent the story of the Exodus to explain their annual Passover celebration? Of course, we would assume that the historical event caused the religious festival, not the other way around.

Second, etiologies exist beyond Genesis 1-11. Here we must again respectfully disagree with Craig when he states,

The primeval history [Genesis 1-11] stand markedly apart from the patriarchal narratives [Genesis 12-50] in their similarity to ancient myths and the employment of etiological motifs like founding present realities in the deep past. After chapter 11 these kinds of similarities and motifs just don’t exist. So everybody seems to recognize that the first eleven chapters are set apart in that sense.[42]

This demonstrably false. Even Bill Arnold states that Genesis 1-36 has a “high concentration of etiologies.”[43] Consider several of the etiologies in Genesis 12 and following:

- God’s promise to Abraham in Genesis 12 is what Von Rad calls “the aetiology of all aetiologies,” because it shows how Abraham’s line would bless all nations—not just Israel.[44]

- God’s prophecy of Egyptian slavery for 400 years is considered an etiology for why the Israelites suffered for so long (Gen. 15:13).[45]

- Abraham and Sarah “laugh” (ṣaḥāq) when they hear about the promised birth of Isaac (Gen. 17:17; 18:12-13; 21:6). After the child is born, they name him “Isaac” (yiṣḥāq). The origin of Isaac’s name was based on the etiology of his parents’ laughter.

- Abraham receives circumcision from God (Gen. 17:9-14), which is the etiology for why the Israelites practiced circumcision.

- Lot’s wife turns into a pillar of salt, which is the etiology for the surrounding “rock formation in the Dead Sea region,”[46] which contains “grotesquely humanlike rock formations in the salt cliffs of the Dead Sea area.”[47]

- The existence of the Moabites is based on the etiology of Lot having sex with his daughters (Gen. 19:37-38).[48]

- Beersheba (beʾēr šeḇaʿ or “well of the seven/oath”[49]) received its name from the etiology of Abraham creating a covenant with Abimelech, in the place where he sacrificed “seven ewes” (Gen. 21:28, 31).[50]

- The name Bethel (Beth-el or “House of God”) is based on the etiology of Jacob seeing God in that location (Gen. 28:18).[51]

- Laban set up a rock pillar for a border, and this is an “etiology for political history” and the setting up of an “international border.”[52]

- The name Mahanaim is based on the etiology of Jacob seeing angels in that particular location (Gen. 32:1-2).[53]

- The name Peniel (“the face of God”) is based on the etiology of Jacob wrestling with God “face to face” (Gen. 32:30). This became an important city east of the Jordan in Israel’s later history (Judg. 8:8; 1 Kin. 12:25).[54]

- Allon-bacuth (“oak of weeping”) received its name because Rebekah mourned the death of her nurse in this place (Gen. 35:8).

- Gilgal (gll “to roll”) received its name from Joshua, because God had “rolled away the reproach of Egypt” (Josh. 5:9).

- The valley of Achor (“valley of disaster”) received its name from the “trouble” (ʿākar) of Achan’s sin (Josh. 7:26).

- The Feast of Purim was based on the etiology of the events recorded in the book of Esther, when Haman had cast “lots” (pûrim) to kill the Jewish people (Est. 9:20-28).[55]

Examples could be multiplied, but surely you can see that these exist far beyond Genesis 1-11. Yet, if etiologies mythologize historical narratives, then all of these events are likewise in the genre of mytho-history. Craig’s argument proves too much.

Third, we find a conspicuous absence of etiologies for major cultural issues. For instance, Genesis gives no explicit etiology for the existence of evil in the world. Craig states, “Genesis 3 does not offer an etiology for evil as such (the deceitful serpent simply shows up in the Garden opposing God).”[56] Von Rad agrees, “There is no aetiology of the origin of evil.”[57] Think about this for a moment: We have etiologies that explain the reason for rainbows, but none that explain the existence of evil.

What about the Sabbath? The observance of the Sabbath was a key pillar of religious and cultural life in Israel, and Craig states that God’s creation week serves as “the most significant [etiology]” for the Sabbath.[58] But not so fast. Look at the text of Genesis one more time: we read nothing about how the creation week was an etiology for the Sabbath in the text of Genesis. It’s only until we get to Exodus 20:9-11 (cf. 31:16-17) that we see the parallel. But this is explained retrospectively (after the fact), not prospectively (before the fact). Regarding the lack of an etiology for the Sabbath, Von Rad notes,

One should be careful about speaking of the ‘institution of the Sabbath,’ as is often done. Of that nothing at all is said here. The Sabbath as a cultic [i.e. worshipping] institution is quite outside the purview. The text speaks, rather, of a rest that existed before man and still exists without man’s perceiving it.[59]

This is a truly shocking observation, because Sabbath observance was so central to Israelite life. Yet Craig considers this “the most significant [etiology]” in Genesis.[60]

Fourth, many examples of etiologies are due to simplistic or subjective interpretations. For example, regarding the slithering serpent, Kidner rejects that this is “merely aetiology” for “how the serpent lost its legs.”[61] As Hamilton notes, to be consistent with this reading, one would need to think that the decree to eat dust is a “change in the snake’s diet.”[62] Instead, this shows how this is symbolic of the Serpent’s defeat and humiliation (cf. Ps. 72:9; Isa. 49:23; Mic. 7:17).

Other suggested etiologies are quite bizarre. For instance, Von Rad believes that the taking of a rib from Adam to create Eve is an etiology that “gives an ancient answer to the question of why ribs surround only the upper half of the human body rather than the entire body.”[63] We find such claims to be too bizarre to engage. The old saying rings true: When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like an etiology. Many of these supposed etiologies are simply subjective, or the subject of over-simplification.

To summarize: Etiologies are allegedly a key reason for understanding Genesis as being in the genre of mytho-history. However, there are several problems with this:

(1) Etiologies do nothing to dehistoricize the Genesis account, because we don’t know if these were the antecedent cause or the subsequent effect of the phenomenon in question.

(2) Etiologies exist throughout the entire book of Genesis—not just chapters 1-11.

(3) We find no explicit etiology for major features of Israelite life—specifically the origin of evil or the institution of the Sabbath.

(4) Many supposed etiologies are simplistic, subjective, or downright strange.

Furthermore, and this is very important, the existence of etiologies proves too much. These would imply that all of Genesis is mytho-history—not just Genesis 1-11. Even Bill Arnold writes, “These distinctive literary features relate to the ancestral accounts of Genesis 12-50 as much as they do to the so-called Primeval History of Genesis 1-11.”[64] Is Craig willing to bite the bullet and consider all of Genesis to be mytho-history? Quite sincerely, I hope not.

REASON #3. Contradictions or inconsistencies imply a metaphorical interpretation

Craig argues that some of the events in the Genesis account are “fantastic” and “palpably false if taken literally.”[65] Because of this, he holds that the original author would’ve understood these discrepancies as metaphorical. He lists several examples of contradictions or “fantastic” accounts that clearly imply a metaphorical interpretation. We will consider only a few below.

(Gen. 2:7) “The LORD God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.” The creation of Adam from the dust seems anthropomorphic. Craig states, “Genesis 3 says that God was… creating Adam out of the dust and doing CPR by blowing into his nose. This is part of the mythological language. And I think we know that because in Genesis 1:1 God is described as the transcendent, Creator of all physical reality. He is not a humanoid deity made out of matter that exists within the universe.”[66]

RESPONSE: For one, the text later states that Adam will “return to the ground” and “to dust” (Gen. 3:19). This language is identical (in Hebrew and English) with that of Genesis 2:7. Do humans metaphorically or figuratively return to the dust of death?—or literally return to the dust of death in burial?

Second, we regularly see anthropomorphic language used of God. For instance, “God remembered Noah” (Gen. 8:1). Under Craig’s genre analysis, this statement would support a mytho-historical genre for Genesis 1-11. However, God also “remembered” the Israelites in slavery (Ex. 2:24), and he “remembered” Hannah’s prayers for a baby (1 Sam. 1:19). This is surely anthropomorphic language, but it does not change the genre of Exodus or 1 Samuel.

Third, Paul cites Genesis 2:7 to refer to an actual historical event. He writes, “It is written, ‘The first man, Adam, became a living soul.’ The last Adam became a life-giving spirit” (1 Cor. 15:45). The contrast is between Adam who passively took in the breath of God, while Jesus actively gives out the breath of God (“a life-giving spirit”).

(Gen. 3:1) “Now the serpent was more crafty than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said to the woman, “Indeed, has God said, ‘You shall not eat from any tree of the garden’?” Craig states, “The snake’s personality and speech cannot (like Balaam’s ass) be attributed to miraculous activity on the part of God lest God become the author of the Fall.”[67] Elsewhere, he states, “In the story he’s just presented as the craftiest of the animals of the field that the LORD God had made. So I take this to be part of the mythological coloring of the story. It’s a story about a snake, who is evil and tempts Adam and Eve to fall, but shouldn’t be taken literally. I think that the snake could certainly be a symbol of evil. But I don’t think we need to think of him as being Satan or a demon incarnate in a snakelike form.”[68] He agrees that John in Revelation interpreted the Serpent this way, but this isn’t what the original author would have believed.

RESPONSE: We agree that God did not open the mouth of the Serpent. In fact, this is a strawman argument, because I have never read a single commentator who holds to such an outlandish view. Rather, what Craig leaves unaddressed is the view of the majority of commentators—namely, that Satan committed this supernatural act (2 Thess. 2:8-9; Ex. 7:11; Job 1:12). Commentators generally hold that Satan literally possessed the Serpent, or perhaps, that the title “the Serpent” is metaphorical for Satan. Yet, traditionally, neither view appeals to a mytho-historical genre:

OPTION #1. Satan possessed this Serpent. If demons can possess human beings (and even force human beings to speak), then they surely could possess an animal. In fact, according to the gospels, demons possessed a herd of pigs (Mt. 8:31-32; Mk. 5:12-13; Lk. 8:33). So, this concept is not unprecedented in the Bible. A spiritual being like Satan could talk through a serpent just as easily as God could talk through a donkey (Num. 22:21-33), a burning bush (Ex. 3:4), or a human being (1 Pet. 4:11; 2 Cor. 5:20). Indeed most interpreters hold to this view.[69]

OPTION #2. This language of “the Serpent” is a metaphorical title for Satan himself. For one, God had already created “creeping things” that crawled on their bellies, and he called them “good” (Gen. 1:24-25). Yet this Serpent is punished by being sent to crawl on the ground (Gen. 3:14). Second, metaphorical language surrounds the Serpent. His punishment of eating dust is likely metaphorical (Gen. 3:14). After all, snakes eat mice—not dust. This is most likely language used for being defeated by God. Similarly, the psalmist writes that the enemies of the king will “lick the dust” (Ps. 72:9). Moreover, this Serpent has “seed” (zeraʿ) or offspring that have hostility with Eve’s offspring (Gen. 3:15). Surely, Satan’s “seed” are metaphorical. Thus Walter Kaiser writes, “The designation ‘the serpent’ is probably a title, not the particular shape he assumed or the instrument he borrowed to manifest himself to the original pair.”[70] In this minority view, while the events of Genesis 3 are historical, it is possible that the text itself uses some symbolism for the Serpent being Satan himself.

The Hebrew word “serpent” (nāchash) is similar to the word for “divination” or “omens” (Num. 23:22; 24:1).[71] The verbal form “divined” (nāḥaš) is also similar (Gen. 30:27, 44:5, 44:15, Lev. 19:26, Deut. 18:10). Thus, this might be a literary connection with occult practice. In the ancient Near East, snakes “were symbolic of life, wisdom, and chaos.”[72] Furthermore, the nail in the proverbial coffin is the NT interpretation of the Serpent, as seen in various passages:

(Rev. 20:2) “He laid hold of the dragon, the serpent of old, who is the devil and Satan” (cf. Rev. 12:9). The term “of old” (archaios) refers to “what has existed from the beginning or for a long time, with connotation of present existence” (BDAG). When John refers to the “serpent of old,” to whom is he referring? I agree with Craig’s assessment from 2018, when he stated, “‘That ancient serpent’ is perhaps a reference back to the serpent in the Garden of Eden who deceived Adam and Eve. He’s called ‘the devil’ and ‘Satan.’”[73] Indeed, I whole heartedly agree.

(1 Jn. 3:8) “The devil has sinned from the beginning.” John assumes his audience knows when and how the devil sinned in the “beginning.” If this doesn’t refer to the Fall in Genesis 3, then to what event is John referring?

(Jn. 8:44) “[The devil] was a murderer from the beginning, and does not stand in the truth because there is no truth in him. Whenever he speaks a lie, he speaks from his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies.” Once again, Jesus assumed that his audience knew what murder the Devil performed “from the beginning.” If this doesn’t refer to the Fall, then to what murderous event is Jesus referring?

(2 Cor. 11:3-4) “I am afraid that, as the serpent deceived Eve by his craftiness, your minds will be led astray from the simplicity and purity of devotion to Christ. 4 For if one comes and preaches another Jesus whom we have not preached, or you receive a different spirit which you have not received, or a different gospel which you have not accepted, you bear this beautifully.” Here, Paul connects the deceit of the “serpent” to “Eve” to the deceit of the false teachers with the Corinthians. Later, he compares the false teachers with Satan himself.

(2 Cor. 11:13-14) “For such men are false apostles, deceitful workers, disguising themselves as apostles of Christ. 14 No wonder, for even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light.” Once again, we agree with Craig’s own views in 2018, when he stated, “We see once again the deceitfulness, the cleverness, and the cunning of Satan in deceiving people and leading them astray.”[74] The language of “leading them astray” originates in verses 3-4, which refers to whom? The Serpent. This was clear to Craig in 2018—even if it isn’t clear to him today in 2020.

While we do not want systematic theology to override our exegesis of a passage, we also should not throw systematic theology out the window. Systematic theology and exegetical theology are not enemies, but allies. These two disciplines (done well) serve to correct one another. Surely, as a systematic theologian, Craig knows this, because he himself regularly interprets Scripture in light of Scripture. It’s only in this recent analysis of Genesis that he forbids NT passages to inform and illuminate his interpretation of the Genesis text.

(Gen. 3:8) “They heard the sound of the LORD God walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the LORD God among the trees of the garden.” Craig calls this the “chief” reason for taking Genesis 1-3 figuratively. God walks, talks, and interacts with the humans in the Garden, which implies that God was physically present. He states, “There are many elements in Genesis 1-3 which, if taken literally, seemed to be palpably false thereby recommending to us a figurative interpretation. Chief among these certainly are the anthropomorphic descriptions of God which are incompatible with the transcendent God described in chapter 1.”[75] Craig states that this implies a “humanoid God” and that the author “could not possibly have intended these anthropomorphic descriptions to be taken literally. They are in the figurative language of myth.”[76]

RESPONSE: Remember Craig’s language: this passage is the “chief” reason for taking Genesis 1-3 figuratively or metaphorically. If this is the best reason, it seriously lacks evidential power.

Though Craig resists this explanation,[77] we understand these depictions to be theophanies (i.e. appearances of God), which occur throughout Scripture. Consider later theophanies that exist in Genesis itself.

(Gen. 15:12) God appears while Abram was asleep. Commentators have noticed the literary similarity between Adam and Abram both being in a “deep sleep” (tardēmâ) while God acted on their behalf (Gen. 2:21; 15:12).[78] In neither case do we have a human seeing this theophany, because both were unconscious. Yet, both texts describe a personal appearance of God.

(Gen. 16:7-13) The angel of the LORD speaks to Hagar, announcing that she will give birth to Isaac. This account contains no language of the angel of the LORD “appearing” to Hagar. Rather, he simply speaks to her, just as God speaks to Adam and Eve. Hagar realizes “the LORD… spoke to her” (Gen. 16:13). Kidner comments, “The angel of the Lord is now disclosed to have been the Lord himself.”[79] Hamilton writes that “the angel is the accompaniment of the deity’s anthropomorphic appearance, rather than being a dilution of it.”[80] And he states, “The angel of Yahweh is a visible manifestation (either in human form or in fiery form) of Yahweh that is essentially indistinguishable from Yahweh himself.”[81]

(Gen. 18:1-33) The LORD appeared to Abraham, ate food, and talked with him. The text states that Yahweh “appeared” to Abraham (v.1). Yet he came in the form of a man (v.2), and he even washed his feet (v.4) and ate food (v.8). Though, remarkably, it is clear that it is Yahweh himself who was present in this human form (vv.1, 17, 33). Originally, “three men” visited Abraham (Gen. 18:2), but only two of the three were actually “angels” (Gen. 19:1). The third was Yahweh himself (vv.1, 17, 33).

(Gen. 32:24-30) Jacob physically wrestled with God. This theophany does not begin with the language of an “appearance” of God. Instead, a man abruptly starts to wrestle Jacob in the middle of the night (v.24). Much like how God changes the names of people (e.g. Abram to Abraham), this mysterious figure changes Jacob’s name to Israel, which literally means “God fights.”[82] Furthermore, this perplexing person tells Jacob, “You have striven with God” (v.28). Jacob named the place Peniel (literally “the face of God”),[83] and he said, “I have seen God face to face, yet my life has been preserved” (v.30). Wenham states that the mysterious man was “implicitly identified with God,”[84] and Hamilton states that Jacob realized that “none other than God himself [had stood] before him.”[85]

To summarize: Craig stated that the “chief” reason for holding to a figurative or metaphorical view of Genesis 1-11 was the “anthropomorphic descriptions of God.”[86] He also stated that the “author could not possibly have intended these anthropomorphic descriptions to be taken literally.”[87] Yet we have comparable or even greater examples of God condescending from his transcendence throughout the rest of Genesis.

To put this another way, according to Craig, the early chapters of Genesis are mytho-history because they depict God as creating, communicating, and walking with the first humans. But Genesis 12-50 are not mytho-history when:

- Abraham falls into a “deep sleep” (tardēmâ) just like Adam (Gen. 2:21; 15:12).

- Hagar directly sees and speaks with God (Gen. 16:13).

- Abraham washes God’s feet and feeds God milk and meat (Gen. 18:8).

- Jacob physically wrestles God for hours on end (Gen. 32:24-30).

Is anyone else confused by these criteria? Furthermore, if God is able to truly incarnate into the person of Jesus of Nazareth, why would we scoff at theophanies which show God entering our world in a human-like form?

Craig rejects localizing language. Some OT scholars have argued that many of the events in Genesis 1-11 could be local, rather than global (see “Different Views of Genesis 1 and 2” for a survey). After all, the “world” to an ancient Israelite could simply be the territory surrounding them—not a satellite photograph of the globe from outer space. This approach would resolve many of the difficulties between science and scripture. Yet Craig states,

I don’t think you can save truth by the device of trying to interpret them as merely local events…. I don’t think the language of the narratives are going to permit that…. You try to save literal truth by localizing it, and I’m not persuaded that that’s legit.[88]

What isn’t “legit” about this approach? Craig states that the universal language does not permit this. But this is precisely the approach of many OT scholars and exegetes. Are all of these interpreters really breaking from what the text permits? Craig’s interpretive grid is vastly overstated.

Craig regularly uses rhetoric to bolster his case. To his credit, it is very unlike Craig to resort to rhetoric. Yet we would be remiss if we didn’t point out some of the rhetorical maneuvering he uses to make his case appear more persuasive:

(1) Craig repeatedly refers to a literal reading as “literalistic.” The term “literalistic” in a discussion of hermeneutics is a pejorative and prejudicial term. Yet Craig repeatedly refers to any grammatical-historical interpretation as “literalistic.” In effect, he is claiming that all other interpreters who reject his genre analysis are confined to a literalistic reading. This is the rhetorical equivalent of the Young Earth Creationist who calls anyone a “liberal” who affirms the antiquity of the universe. This scores points rhetorically, but not rationally.

(2) Craig places the worst option as the second best option. All of a sudden, Craig has become a big fan of Young Earth Creationism. He states, “The two most plausible interpretive options are the literal Young Earth Creationist interpretation and the mytho-historical interpretation. Of these two, I find the mytho-historical interpretation to provide a better genre analysis.”[89] My, my, my. If one of the two “most plausible interpretive options” is Young Earth Creationism, then the other one is almost guaranteed to win by default. It’s like putting Michael Cera in the ring for celebrity boxing… No matter who you put in the other corner, it’s gonna be a slaughter! Craig must realize that such a statement rhetorically stacks the deck in his favor.

(3) Craig uses loaded language to parody a contrary view. Craig refers to the “humanoid god,”[90] who performed “CPR by blowing into [Adam’s] nose”[91] and who created Eve from a “rib floating in the air.”[92] At best, this is uncharitable language. At worst, these are rhetorical tactics used to make any grammatical-historical reading look absurd.

To summarize: This third line of evidence for the mytho-historical genre offers a simplistic and reductionistic understanding of alternative views. This leads to binary alternatives, and perhaps, even a reliance upon rhetorical devices.

Conclusion

For over 50 years, William Lane Craig has held a steady hand at the wheel as a thought-leader in the areas of philosophy, theology and apologetics. That’s why it personally pains me to watch him take such a sharp and sudden turn toward the end of his career. Despite his education, experience, and erudition, he is simply in the wrong on this one, and his view carries significant consequences.

Craig desires to write a philosophical and systematic theology to close out his career. I greatly look forward to his forthcoming work. Yet can he not see that Genesis 1-11 lays the foundation for systematic theology? Core Christian doctrines begin in these opening chapters—not the least of which are the existence of God, creation, the image of God in humans, the foundation for marriage, free will, evil, and humanity’s ancient enemy Satan. Yet, to Craig, “It’s probably futile to try to discern to what extent the narratives are to be taken literally—to identify which parts are figurative and which parts are historical.”[93] Can he not see that this genre analysis is not only unjustifiable, but also poisonous to his own field of systematic theology?

We heartily endorse Craig’s earlier view from 2013, where he remained agnostic on which interpretation of Genesis was correct. He said,

There is quite a wide range of interpretations of Genesis 1 that have been defended by Bible believing evangelical scholars. It is not the case that we are boxed into just one interpretation that is valid and sound for anyone who is a Bible believing Christian. There is quite a wide range of interpretations of Genesis 1. You might say, “Well, then which of these interpretations is the best, if any? Which would you endorse?” Here I have to give my candid view—I don’t know! I have been studying and reading on this subject for a long time and I am still uncertain as to what is the best view. So I don’t have a sort of hard and fast opinion on this. But I think that is alright. I think that the Christian can be open-minded with respect to various interpretations of biblical passages and doesn’t need to pigeon hole everybody into just one acceptable interpretation. I hope that as a result of this survey it has given you an appreciation for the rich diversity of views that Bible believing scholars have taken on this passage.[94]

What is wrong with this approach? By offering various acceptable hermeneutical models, we show a clear respect for the biblical data, as well as an open mindedness to the findings of the natural sciences. Craig has only recently become uncomfortable appealing to agnosticism on this issue, and he seems set on “unscrewing the inscrutable.” But this is mistaken. Instead of offering a multitude of biblically sound models, Craig is opting for only one model, which—in my estimation—is unjustified and biblically unsound.

Making up your own mind

If you feel the impulse to follow Craig’s mytho-historical genre for Genesis, pause to consider these questions. These may help sharpen your own thinking as you evaluate this perspective:

- What is mytho-history? Seriously, what is it? Are you willing to import a literary genre for Genesis that you cannot clearly define? If you cannot define it, how can you even begin to defend it?

- What reasons do you have for identifying Genesis 1-11 as mytho-history? If you accept this genre without sufficient reasons, what will stop you from accepting alien genres for other parts of Scripture?

- On what basis do you consider Genesis 1-11 as mytho-history, while understanding Genesis 12-50 as straightforward history?

- What interpretive boundaries does mytho-history offer to avoid dehistoricizing the text of Genesis?

- What is wrong with being open to several different models that seek to synthesize science and scripture? (see “Different Views of Genesis 1 and 2” for a survey) What do we lose if we have several different plausible explanations, rather than holding firmly to only one?

- If you adopt the genre of mytho-history, how will you know which parts are literal and which parts are metaphorical?

- How confident are you to teach through Genesis 1-11?

While I have the utmost respect and appreciation for William Lane Craig, his recent conclusions on Genesis are simply false and hazardous, moving the discussion down the wrong path. And I for one am not going to follow him to find out where that path leads.

[1] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 22): The Central Truths Expressed in Genesis 1-11.

[2] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 22): The Central Truths Expressed in Genesis 1-11.

[3] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 11): An Assessment of the Monotheistic Hebrew Myth Interpretation.

[4] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 11): An Assessment of the Monotheistic Hebrew Myth Interpretation.

[5] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 16 minutes.

[6] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 17): The Genre of Mytho-History.

[7] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 17): The Genre of Mytho-History.

[8] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 12 minutes.

[9] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 14 minutes.

[10] Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.31.

[11] Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.31.

[12] Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.31.

[13] Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.31.

[14] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 17): The Genre of Mytho-History.

[15] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 22): The Central Truths Expressed in Genesis 1-11.

[16] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 17): The Genre of Mytho-History.

[17] Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Eridu Genesis,” [1981], in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, ed. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, Sources for Biblical and Theological Studies (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1994), p. 140.

[18] Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Eridu Genesis,” [1981], in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, ed. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, Sources for Biblical and Theological Studies (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1994), p. 140.

[19] Gordon Wenham, “Genesis 1-11 as Protohistory” In C. Halton & S. N. Gundry (Eds.), Genesis: History, Fiction, or Neither? Three Views on the Bible’s Earliest Chapters (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2015), p.74.

[20] To be fair, Arnold goes on to describe levels of confidence in reconstructing the historical milieu, but he opens by sharing just how sparse it is. Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.24.

[21] Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Eridu Genesis,” [1981], in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, ed. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, Sources for Biblical and Theological Studies (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1994), p. 131. Cited in Gordon Wenham, Rethinking Genesis 1-11, p.24.

[22] Gordon Wenham, Rethinking Genesis 1-11: The Didsbury Lecture Series (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013), p.24.

[23] Gordon Wenham, Rethinking Genesis 1-11: The Didsbury Lecture Series (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013), p.24.

[24] Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Eridu Genesis,” [1981], in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, ed. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, Sources for Biblical and Theological Studies (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1994), p. 141. Cited in Gordon Wenham, Rethinking Genesis 1-11, p.24.

[25] Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Eridu Genesis,” [1981], in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, ed. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, Sources for Biblical and Theological Studies (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1994), p. 141. Cited in Gordon Wenham, Rethinking Genesis 1-11, p.24.

[26] Even Bill Arnold admits, “None of the extrabiblical examples have precise parallels with the use of genealogies in Genesis 1-11, either in form or function. Most ancient Near Eastern genealogies are intended to establish a certain status for a political leader or official, whereas in the Primeval History genealogies are blended with narrative portions to move the reader forward in history. The characters involved are not political leaders rooted in the past; rather, they are key figures in religious history highlighted for their failures as much as for their successes.” Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.32.

[27] Bill T. Arnold, Encountering the Book of Genesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p. 208, 220.

[28] Bill T. Arnold, Encountering the Book of Genesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p. 38.

[29] Bill T. Arnold, Genesis: The New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.68.

[30] Bill T. Arnold, Genesis: The New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.11.

[31] Bill T. Arnold, Encountering the Book of Genesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p. 38.

[32] Claus Westermann, Genesis (trans. David Green, London: T&T Clark International, 2004), p.66.

[33] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.150.

[34] Claus Westermann, Genesis (trans. David Green, London: T&T Clark International, 2004), p.82.

[35] Albrecht Alt, Kleine Schriften, I (Munich: Beck, 1953).

[36] Hermann Gunkel, Die Sagen der Genesis.

[37] Martin Noth, Das Buch Josua (Tubingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1938).

[38] Collins gives the example of a scar on his knee, and how it has great teaching power, but it is also true. C. John Collins, Did Adam and Eve Really Exist? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2011), p.63.

[39] See footnote 19. C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing Company, 2006), p.14.

[40] Emphasis mine. James Hoffmeier, “Genesis 1-11 as History and Theology.” In C. Halton & S. N. Gundry (Eds.), Genesis: History, Fiction, or Neither? Three Views on the Bible’s Earliest Chapters (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2015), p.55.

[41] Bright continues, “I should not wish to deny that the aetiological factor is present…. But I should like to submit that, where historical tradition is concerned, not only can it be proved that the aetiological factor is often secondary in the formation of these traditions, it cannot be proved that it was ever primary… An etiology presumes the tradition and therefore cannot be the cause of the tradition.” John Bright, Early Israel in Recent History Writing (London: SCM, 1956), p.91.

[42] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 21): Why Read Genesis 1-3 Figuratively?

[43] Bill T. Arnold, Genesis: The New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.12.

[44] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.24.

[45] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.187.

[46] Robert Altar, Genesis (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996), p.89.

[47] Bill T. Arnold, Genesis: The New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.186.

[48] Claus Westermann, Genesis (trans. David Green, London: T&T Clark International, 2004), p.145.

[49] John H. Sailhamer, Genesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), p.188.

[50] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.236.

[51] Claus Westermann, Genesis (trans. David Green, London: T&T Clark International, 2004), p.199.

[52] Robert Altar, Genesis (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996), p.175.

[53] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.314.

[54] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.323.

[55] Hamilton, V. P. (1999). 1749 פּוּר. R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer Jr., & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 720). Chicago: Moody Press.

[56] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 14): Etiological Motifs in Genesis 2.

[57] Von Rad cites Westermann here. See Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.87.

[58] Reasons to Believe: Human Origins Workshop 2020—Panel Response (June 5, 2020). 43-44 minutes.

[59] Emphasis mine. Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.62.

[60] Reasons to Believe: Human Origins Workshop 2020—Panel Response (June 5, 2020). 43-44 minutes.

[61] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.75.

[62] Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), p.196.

[63] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), p.84.

[64] Bill T. Arnold, “The Genesis Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, ed. Bill T. Arnold and Richard S. Hess (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p.24.

[65] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 20): Why Think Genesis 1-11 is Mytho-History?

[66] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 17-18 minutes.

[67] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 20): Why Think Genesis 1-11 is Mytho-History?

[68] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 43-44 minutes.

[69] Hugh Ross, Navigating Genesis (Reasons to Believe, Covina, CA: 2014), p.110.

John C. Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), p.83.

Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.72.

[70] Walter Kaiser, The Messiah in the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Pub., 1995) 38.

[71] Alden, R. (1999). 1347 נחשׁ. R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer Jr., & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 572). Chicago: Moody Press.

[72] Gordon Wenham, Genesis 1-15 (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), p.72.

[73] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Doctrine of Creation (Part 21): The Names of Satan. November 6, 2018.

[74] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Doctrine of Creation (Part 23): The Nature of Demons. November 28, 2018.

[75] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 21): Why Read Genesis 1-3 Figuratively?

[76] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 20): Why Think Genesis 1-11 is Mytho-History?

[77] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 21): Why Read Genesis 1-3 Figuratively?

[78] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, Word Biblical Commentary (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1987), p.331.

[79] Derek Kidner, Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1967), p.138.

[80] Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), p.450.

[81] Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), p.451.

[82] Gordon Wenham, Genesis 16-50 (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), p.296.

[83] Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), p.336.

[84] Gordon Wenham, Genesis 16-50 (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), p.297.

[85] Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), p.337.

[86] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 21): Why Read Genesis 1-3 Figuratively?

[87] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 20): Why Think Genesis 1-11 is Mytho-History?

[88] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Life & Bio-Diversity – Part 27: Scientific Evidence Pertinent to the Origin and Evolution.

[89] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Life & Bio-Diversity – Part 27: Scientific Evidence Pertinent to the Origin and Evolution.

[90] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 20): Why Think Genesis 1-11 is Mytho-History?

[91] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 17-18 minutes.

[92] Interview with Dr. William Lane Craig, “The Book of Genesis: With Dr. William Lane Craig,” Remnant Radio, 51 minutes.

[93] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 3.” Excursus on Creation of Life and Biological Diversity (Part 22): The Central Truths Expressed in Genesis 1-11.

[94] William Lane Craig, “Defenders Class 2.” Creation and Evolution (Part 12), July 8, 2013.