The book of Revelation claims to be a book of “prophecy” (Rev. 1:1, 3, 11, 19; 22:6-10, 16, 18-20). Specifically, it claims to foretell future events: “The things which must soon take place” (Rev. 1:1; cf. Rev. 1:19). Preterists claim that the Jewish War (AD 66-70) fulfilled most of these predictions in the book of Revelation. Therefore, in order for Preterism to sustain itself, the book of Revelation must date before AD 66. This observation is as obvious as it is uncontroversial. Indeed, preterist Kenneth Gentry writes that the preterist view would “go up in smoke.”[1] Elsewhere, he is more specific:

The book of Revelation claims to be a book of “prophecy” (Rev. 1:1, 3, 11, 19; 22:6-10, 16, 18-20). Specifically, it claims to foretell future events: “The things which must soon take place” (Rev. 1:1; cf. Rev. 1:19). Preterists claim that the Jewish War (AD 66-70) fulfilled most of these predictions in the book of Revelation. Therefore, in order for Preterism to sustain itself, the book of Revelation must date before AD 66. This observation is as obvious as it is uncontroversial. Indeed, preterist Kenneth Gentry writes that the preterist view would “go up in smoke.”[1] Elsewhere, he is more specific:

If the late-date of around A.D. 95-96 is accepted, a wholly different situation would prevail. The events in the mid to late 60s of the first century would be absolutely excluded as possible fulfillments. The prophecies within Revelation would be opened to an abundance of speculative scenarios, which could be extrapolated into the indefinite future. Revelation might… focus exclusively on the end of history, which would begin approaching thousands of years after John’s time, either before, after, or during the tribulation or the millennium. The purpose of Revelation would then be to show early Christians that things will get worse, that history will be a time of constant and increased suffering for the Church.[2]

Likewise, preterist R.C. Sproul writes,

If the book was written after A.D. 70, then its contents manifestly do not refer to events surrounding the fall of Jerusalem—unless the book is a wholesale fraud, having been composed after the predicted events had already occurred… The burden for preterists then is to demonstrate that Revelation was written before A.D. 70.[3]

In other words, if Revelation dates after AD 70, then Preterism is toast. Therefore, the late-date of Revelation is the Achilles’ heel of Preterism.

Surprisingly, many Preterists do not address this key issue. For instance, in his 700-page commentary on Revelation, Preterist David Chilton spends only three pages securing the early date for the book. (By contrast, he spends nine pages interpreting the “666” of Revelation 13:18!)[4] Yet, if he is wrong about his early dating of Revelation, then his entire commentary is worthless.

By contrast, if one is a futurist, one could hold to either the early or late date. It wouldn’t matter either way—for either date would make the predictions in Revelation future for a futurist. For instance, the late Zane Hodges is a futurist, who holds to the early date of Revelation.[5] Hence, the dating of Revelation is relatively inconsequential for the futurist, but it is simply essential for a preterist to defend a pre-AD 70 date.

Table of Contents

The Scholarly Consensus Favors the Domitianic Date. 4

Evidence for the Domitianic Date (AD 95). 5

OBJECTION #1. Irenaeus wrote about John’s age—not the date of Revelation. 7

OBJECTION #2: Irenaeus was mistaken in his assertion. 10

OBJECTION #3. The Church Fathers all get their data from Irenaeus. 12

Clement of Alexandria (AD 215). 12

Summary of the External Evidence. 16

Evidence for the Early Date. 19

What about the mention of the Temple in Revelation 11?. 19

Why does John record the history of the destruction of Jerusalem?. 20

Does Widespread Persecution imply an Early Date?. 21

The Muratorian Fragment (AD 170). 22

Clement of Alexandria (AD 215). 26

Watch our debate with Dr. Dean Furlong HERE

The Scholarly Consensus Favors the Domitianic Date

The Domitianic date for Revelation is the consensus in scholarship today. Osborne states that the Domitianic date “prevailed from the second through the eighteenth centuries and again in the twentieth century, while the Neronic date dominated the nineteenth century.”[6] He’s right. From the 20th century until today, the Domitianic date has regained the consensus of scholarship. Many scholars affirm Osborne’s assertion:

D.A. Carson & Douglas Moo: “Most scholars have been inclined to follow Irenaeus in his dating of Revelation at the close of the reign of Domitian.”[7]

Mitchell Reddish: “widely accepted.”[8]

G.K. Beale: “consensus among twentieth-century scholars.”[9]

Colin J. Hemer: “broad consensus… widely accepted.”[10]

Raymond Brown: “scholarly majority.”[11]

Mark Allan Powell: “dominant theory… most common approach.”[12]

Alan Johnson: “generally accepted date.”[13]

Craig Keener: “preferred by most scholars.”[14]

Steve Gregg (preterist): “Most modern scholars appear to favor a later date in the time of Domitian for the writing of Revelation.”[15]

Donald Guthrie: “The most widely held view is that this Apocalypse was written during the reign of Domitian… The majority of scholars still prefer a date in the time of Domitian.”[16]

David Aune: “During the last half of the twentieth century, most scholars concerned with the question expressed support for the Domitianic date.”[17]

Robert Mounce: The denial of the Domitianic date is held by “very few contemporary writers.”[18]

To be clear, we shouldn’t determine truth by taking a vote. It’s possible that the consensus of scholars is wrong. However, these collective voices should weigh on early-date advocates when the majority of scholars disagree with them.

Evidence for the Domitianic Date (AD 95)

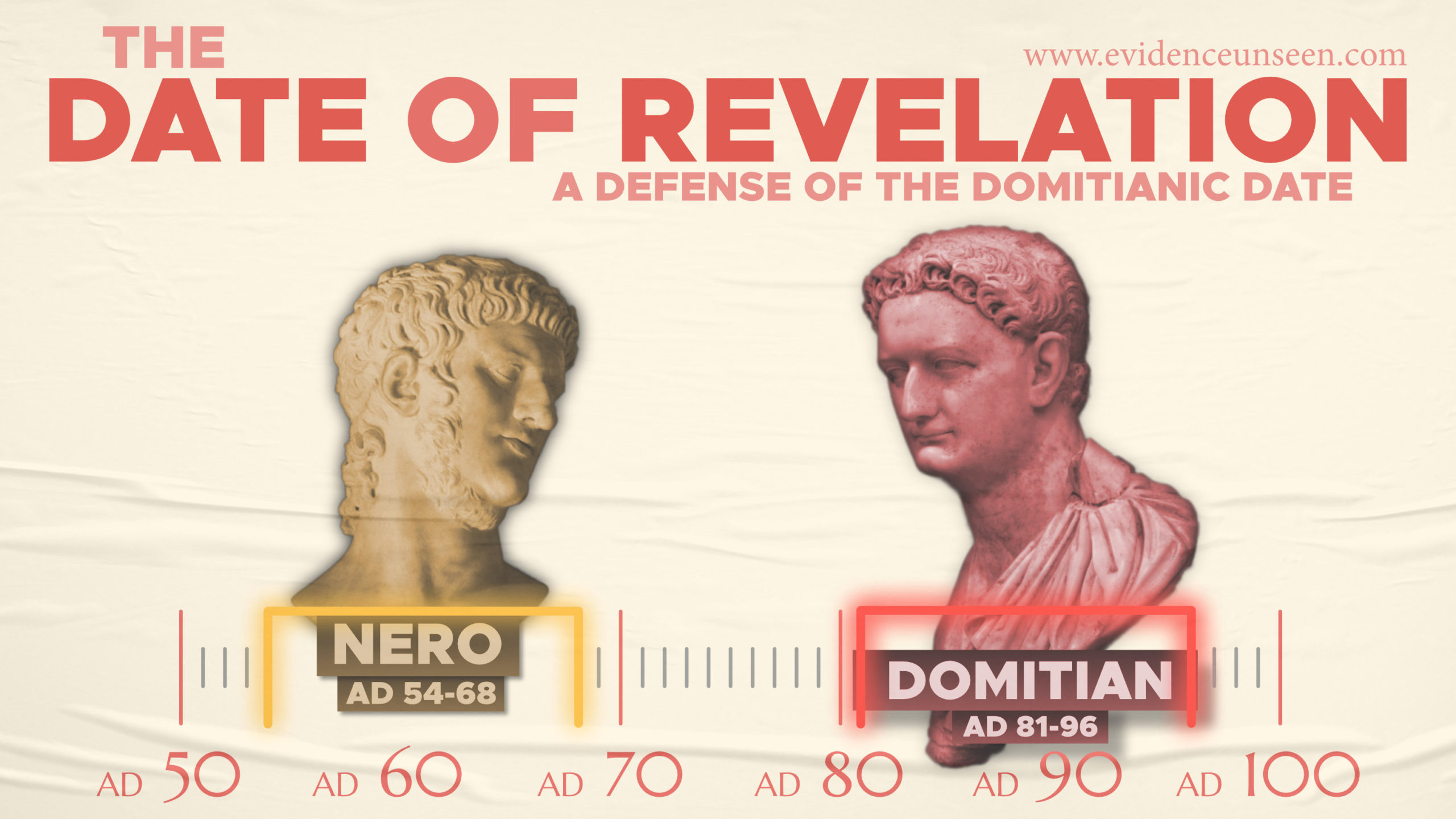

We hold to the “late date” of Revelation which places the book toward the end of the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian (~AD 95). By contrast, preterists affirm the “early date,” placing the book during the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero (AD 65). We will argue that two independent lines of evidence support the late date: (1) external evidence and (2) internal evidence.

(1) External evidence

What is external evidence? This type of evidence comes from outside of the book itself, supporting its late date. External evidence is a standard way to discover the date of a historical work. In the case of Revelation, several lines of external evidence can be offered for the late date of Revelation.

Irenaeus (AD 120-200)

Why is Irenaeus’ testimony so important? Irenaeus received his historical data about the date of Revelation directly from Polycarp (the bishop of Smyrna),[19] and Polycarp was a direct disciple of John—the author of Revelation.[20] Therefore, Irenaeus had a direct line of contact to the author of this book. Even preterist Steve Gregg (an advocate for the early date) acknowledges the import of Irenaeus’ testimony:

If Irenaeus is saying that the vision was seen at this late date, then his witness carries considerable weight. In view of the claim that Irenaeus knew Polycarp, who in turn knew the apostle John, he might well be expected to have accurate information regarding the time of John’s imprisonment on Patmos.[21]

Moreover, Irenaeus lived in Smyrna as a young man, where he claims to have listened to Polycarp.[22] Of course, Smyrna was a Greek a city where Revelation circulated, and to whom one of the seven letters was addressed (Rev. 2:8-11).

What did Irenaeus write? In his book Against Heresies, Irenaeus devotes an entire chapter (5:30) to the number of the beast (Rev. 13:18).[23] Irenaeus originally wrote in Greek, but our existing manuscripts of Irenaeus only have later Latin translations. Fortunately, however, Eusebius (AD 260-340) preserved this section from Irenaeus in the original Greek (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3; 5.8.6). In this section, Irenaeus begins by speaking about the identity of the Antichrist (Rev. 13:18), and then he addresses the book of Revelation as a whole:

McGiffert Translation (1890): “If it were necessary for his name to be proclaimed openly at the present time, it would have been declared by him who saw the revelation. For it was seen not long ago, but almost in our own generation, at the end of the reign of Domitian” (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3).[24]

Deferrari Translation (1953): “If it had been necessary to proclaim his name openly, it would have been spoken by him who saw the apocalypse. For it was seen not long ago, but almost in our own generation, toward the end of the reign of Domitian” (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3).[25]

Maier Translation (2011): “Had it been necessary to announce his name clearly at the present time, it would have been stated by the one who saw the revelation. For it was seen not long ago but nearly in our own time, at the end of Domitian’s reign” (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3).[26]

Roberts Translation: “We will not, however, incur the risk of pronouncing positively as to the name of Antichrist; for if it were necessary that his name should be distinctly revealed in this present time, it would have been announced by him who beheld the apocalyptic vision. For that was seen no very long time since, but almost in our day, towards the end of Domitian’s reign” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 5.30).[27]

Schaff Translation: “We will not, however, incur the risk of pronouncing positively as to the name of Antichrist; for if it were necessary that his name should be distinctly revealed in this present time, it would have been announced by him who beheld the apocalyptic vision. For that was seen no very long time since, but almost in our day, towards the end of Domitian’s reign” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 5.30).[28]

Domitian was assassinated on September 18, AD 96. This means that the “end of the reign of Domitian” would date Revelation around AD 95. This is direct and explicit testimony to the dating of Revelation.

OBJECTION #1. Irenaeus wrote about John’s age—not the date of Revelation.

Early-date advocates argue that the subject of the word “seen” (heorathe) refers to John himself—not the “apocalypse.” From this perspective, Irenaeus was commenting on the fact that John was seen living all the way into Domitian’s reign. He wasn’t referring to the date when John wrote Revelation.

Before we begin, let’s consider if this objection is accurate. Even if the early date criticism of this passage from Irenaeus is correct, what does it prove? Answer? Nothing. It surely takes away a key line of evidence from the late date, but it doesn’t add evidence to the early date view. It would simply leave us more agnostic of the date. At the same time, we find this objection unpersuasive for a number of reasons:[29]

First, the immediate context refers to the “revelation,” not to John. When interpreting the meaning of a pronoun, grammarians look to the closest antecedent (i.e. “The Last Antecedent Rule”).[30] To explain this interpretive principle, consider an example:

“Mary picked up Jill at the store. She needed to buy groceries.”

In this sentence, who does “she” refer to? Mary or Jill? According to this commonsense hermeneutical principle, the pronoun “she” replaces Jill—not Mary. With this simple interpretive principle in mind, look again at the citation from Irenaeus. What does the “it” refer to?

“Had it been necessary to announce his name clearly at the present time, it would have been stated by the one who saw the revelation. For it was seen not long ago but nearly in our own time, at the end of Domitian’s reign” (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3).[31]

In context, the nearest antecedent is “the revelation.” Moreover, “the revelation” is the subject of this chapter.

Second, the greater context refers to the “revelation,” not to John. The main subject of Irenaeus’ chapter is about Revelation and the meaning of the number of the Beast being “666” (Rev. 13:18). When Eusebius cites this passage from Irenaeus, he picks up on this main point, creating bookends that refer to Revelation. Before Eusebius cites this excerpt from Irenaeus, he writes, “[Irenaeus] speaks about the Apocalypse of John.” In other words, the book of Revelation is the subject—not John himself. Moreover, after the citation, Eusebius concludes by writing, “These things are related by the aforesaid about the Apocalypse” (Church History, 5.8.5-7.). Modern people might be confused as to whether the subject was the “apocalypse,” but Eusebius is quite clear: John saw “the Apocalypse.”

Third, the verb “saw” (horaō) seems to act on the same direct object. Consider an example from English. What is being eaten in both sentences?

“Mary ate the pie. [‘It’ / ‘She’] was eaten last night.”

While this sentence contains different forms of the verb “to eat,” they both seem to carry the same direct object: The pie. If we had an interpretive choice, we would never interpret the pronoun “it” to refer to Mary. Why not? The same verb “eat” seems to be performing an action on the direct object (i.e. the pie), not on the subject (“Mary”). In fact, if we understood the “it” to refer to Mary, this would imply that another subject entered the scene without warning to eat our dear friend Mary! With this grammatical lesson in mind, consider Irenaeus’ statement once again. What is being “seen” in both sentences?

“The one who saw (heorakotos) the revelation. For it was seen (heorathe) not long ago…” (Eusebius, Church History 3.18.3).[32]

Again, if we read the verb in light of its earlier usage, it is performing the action on the same object: “The Revelation.” Moreover, throughout the book of Revelation, John repeatedly uses the word “see” (horaō) to describe how he witnessed his visions (Rev. 1:7; 11:19; 12:1, 3; 19:10; 22:4, 9). This would be a good word for Irenaeus to us to describe how John “saw” (horaō) the Revelation. After all, he would be using John’s own word.

Fourth, the alternate reading doesn’t fit with Irenaeus’ earlier comments about John’s lifespan. Earlier in his work, Irenaeus states that John lived into the reign of Trajan (AD 98-117), not just Domitian (see Against Heresies, 2.22.5; 3.3.4).[33] Why then would Irenaeus feel the need to point out that John lived through Domitian’s reign? This would be like saying, “I grew to six feet tall,” after repeatedly saying, “I am currently 6 foot 2 inches.” Obviously, someone was this lower height before growing to his full height. This is what makes Irenaeus’ statement so odd if we accept the early date reading. If Irenaeus knew that John lived in the reign of Trajan (AD 98-117), why did he feel the need to mention him being seen alive during the reign of Domitian in AD 95?

Fifth, all reputable English translations of Eusebius have translated this as referring to “the Revelation.” These translations state something to the effect of, “It was seen not long ago,” rather than, “He was seen not long ago.”[34] Indeed, none of these translations even contain a footnote or an alternate reading. Apparently, no one communicated just how confusing and ambiguous this text was to these various translators.

Fifth, no one suggested, let alone accepted, a revised reading of Irenaeus’ statement for 1,600 years. Think about that. If Irenaeus’ statement regarding the date of Revelation is really so ambiguous, why don’t we possess a single criticism of this text from any Christian for over 1,600 years? In fact, why did this alternate early date reading not appear for 1,600 years—until the time of Johannes Wetstein in 1751?[35] Finally, does it bother you that the first person to suggest a revisionist reading was a preterist?

Conclusion

We think that these five lines of evidence strongly suggest that the historical reading of Irenaeus stands on solid ground: John received the Revelation at the end of Domitian’s reign. We’re not alone in this conclusion. Even early date advocate J.A.T. Robinson writes, “The translation has been disputed by a number of scholars on the ground that it means that he (John) was seen; but this is very dubious.”[36] Likewise, David Aune writes, “The passive verb heorathe, ‘he/she/it was seen,’ does not appear to be the most appropriate way to describe the length of a person’s life; it is much more likely that heorathe means ‘it [i.e., ‘the Apocalypse’] was seen,’ referring to the time when the Apocalypse was ‘seen’ by John of Patmos.”[37] Finally, G.K. Beale writes, “The majority of patristic writers and subsequent commentators up to the present understand Irenaeus’s words as referring to the time when the Apocalypse ‘was seen.’”[38]

OBJECTION #2: Irenaeus was mistaken in his assertion.

Early-date advocates sometimes bite the bullet and agree that Irenaeus was indeed recording the date of Revelation to AD 95. However, they argue that Irenaeus simply erred. Typically, they point to one of Irenaeus’ critical errors: He claimed that Jesus was 40 years old when he died.[39] If Irenaeus could be wrong about so significant a fact, couldn’t he also be wrong about the date of Revelation? However, a number of counterarguments have been argued:

First, Irenaeus wasn’t far off from Jesus’ actual age at death. If Jesus was born in 4/5 BC and he died in AD 33, this would place him at age 38 in his death. Of course, Irenaeus placed the birth of Christ to 4/3 BC in the 41st year of Augustus (Against Heresies 3.21.3). This would put Jesus at age 36 in his death. This is far from an outrageous historical error—only being off by a few years.

Second, this statement from Irenaeus was not a historical error, but a hermeneutical error. Jesus’ religious opponents asked him, “You are not yet fifty years old, and have You seen Abraham?” (Jn. 8:57) From this, Irenaeus wrongly believed that Jesus must have been in his forties (contra Lk. 3:23). But this was clearly an interpretive error. What student of Scripture is not guilty of misinterpreting the Bible from time to time?

Third, Irenaeus was very particular about his dating of Revelation. Not all historical claims should be treated equally. Even if Irenaeus erred on one historical fact, this doesn’t mean that he erred in everything. Irenaeus seems to have a clear understanding of the dating of Revelation. He not only mentions the reign of Domitian, but also the fact that it occurred at the end of this era. This specificity of language implies precision—not haphazard guessing. Hitchcock writes, “This specific dating of Revelation suggests that Irenaeus possessed special, intimate knowledge of the timing and conditions under which Revelation was written.”[40]

Fourth, Irenaeus lived in Smyrna, where Revelation originally circulated. This creates a chain of evidence leading to the author himself. Thus, Hitchcock observes, “Irenaeus’ mistake about the length of Jesus’ earthly ministry, as discussed previously, was based on his misinterpretation of a particular biblical text; whereas, his information about the date of Revelation was evidently received directly from Polycarp. It is much easier to misinterpret a biblical text than to misunderstand direct verbal testimony from someone as respected as Polycarp.”[41]

Fifth, Irenaeus is typically considered a very reliable historical source. Even early date advocates like the great historian Philip Schaff speak of Irenaeus’ testimony as “clear and weighty.”[42] Likewise, John A.T. Robinson writes, “The credit of this witness is good.”[43]

Preterist Hank Hanegraaff seems confused regarding Irenaeus’ reliability: He often appeals to the historical reliability of Irenaeus when supporting the historicity of the NT documents;[44] however, he quickly repeals his confidence in Irenaeus’ reliability when dating the book of Revelation.[45] So, which is it? Is Irenaeus a reliable source or not? Hanegraaff suddenly finds Irenaeus unreliable when his preterism is on the line. This sort of inconsistency could make your head spin.

OBJECTION #3. The Church Fathers all get their data from Irenaeus

Gentry argues that these sources don’t add up as separate witnesses, but merely repeat the first witness: Irenaeus.[46] Yet, Gentry shoots himself in the foot when he also notes that the “church fathers did not accept necessarily Irenaeus’s authority as conclusive” in other areas.[47] Gentry goes on to note that Eusebius didn’t believe Irenaeus in two key areas: (1) Papias meeting John[48] and (2) the apostle John’s authorship of Revelation.[49] Either the church fathers all blindly adopted Irenaeus’ dating of John, or they are shown to question Irenaeus’ authority. Gentry can’t have it both ways.

Clement of Alexandria (AD 215)

Clement of Alexandria lived in Egypt in Africa. It goes without saying that he lived far away from Irenaeus who lived in Lyons, France. As an independent testimony, Clement states that John was released from exile after a certain “tyrant” had died. He writes:

“When on the death of the tyrant he removed from the island of Patmos to Ephesus, he used to go off, when requested, to the neighbouring districts of the Gentiles also, to appoint bishops in some places, to organize whole churches in others, in others again to appoint to an order some one of those who were indicated by the Spirit.”[50]

Eusebius understands the expression “the death of the tyrant” to refer to “the death of Domitian.” Eusebius writes:

“That very disciple whom Jesus loved, at once both Apostle and Evangelist, was still alive and administered the churches there, having returned from his exile on the island after the death of Domitian… Clement likewise has indicated the time.”[51]

Tertullian (AD 150-212)

Tertullian lived in Africa, and he was a great apologist and Latin church father. He describes how Peter and Paul faced martyrdom in Rome. Yet, by contrast, John was exiled instead of being killed. He writes:

“You have Rome, from which there comes even into our own hands the very authority (of apostles themselves). How happy is its church, on which apostles poured forth all their doctrine along with their blood! Where Peter endures a passion like his Lord’s! Where Paul wins his crown in a death like John’s where the Apostle John was first plunged, unhurt, into boiling oil, and thence remitted to his island-exile!”[52]

Nothing in the text tells us the timing of these events—only the location of these events—namely, Rome. After all, Tertullian is surely not claiming that Peter and Paul were executed at the same moment—only that they both died in Rome.[53] Similarly, nothing in the text requires us to think that John was exiled at the same time as Peter and Paul faced martyrdom (in AD 67). So, this passage from Tertullian does support the early date. However, it does support the late date for two reasons:

First, why were Peter and Paul executed, while John was only exiled? This is quite a difficult question to answer as an early date advocate. After all, Nero made himself famous for crucifying Christians,[54] and he had both Peter and Paul put to death.[55] But why would he execute a Roman citizen like Paul, and only exile a Jewish man like John?

Advocates of the late date have a plausible answer: Domitian was known for exiling and banishing prisoners to islands.[56] Dio Cassius refers to Domitian’s practice of banishment four times in his history.[57] Specifically, Domitian exiled his cousin Flavia Domitilla on the charge of “atheism.” Dio Cassius states that this was a “charge on which many others who drifted into Jewish ways were condemned.”[58] Of course, the Romans also accused Christians of being “atheists” as well because they rejected the Roman pantheon of gods.[59] Because of her “atheism” (Judaism? Christianity?), Domitilla was banished to Pandateria. Eusebius held that Flavia Domitilla was a Christian.[60] Whether this is true or not, don’t miss the big picture: “This historical evidence demonstrates that religion could result in execution or exile.”[61] Blomberg adds, “There is no evidence of Christians being banished from their homelands by the government prior to this date.”[62]

Second, both Eusebius and Jerome interpreted this passage from Tertullian to refer to the reign of Domitian. Immediately after citing from one of Tertullian’s works, Eusebius writes,

“After Domitian had reigned…, the Roman Senate decreed that the sentences of Domitian be annulled and that those who had been banished unjustly return to their homes and receive back their property. Those who have committed the events of those times to writing relate this. The story of our ancient writers relates that at that time the Apostle John, after his exile to the island, took up his abode at Ephesus.”[63]

Likewise, Jerome writes:

“John is both an Apostle and an Evangelist, and a prophet… He saw in the island of Patmos, to which he had been banished by the Emperor Domitian as a martyr for the Lord, an Apocalypse containing the boundless mysteries of the future. Tertullian, more over, relates that he was sent to Rome, and that having been plunged into a jar of boiling oil he came out fresher and more active than when he went in.”[64]

Eusebius and Jerome both claim that they are relying on earlier historical tradition(s). In both cases, they interpret Tertullian as making this claim.

Victorinus (AD 304)

Victorinus wrote our earliest surviving commentary on the book of Revelation (AD 304). In it, he affirms the Domitianic date. He writes,

“When John said these things he was in the island of Patmos, condemned to the labor of the mines by Caesar Domitian. There, he saw the Apocalypse; and when grown old, he thought that he should at length receive his quittance by suffering, Domitian being killed, all his judgments were discharged. And John being dismissed from the mines, thus subsequently delivered the same Apocalypse which he had received from God.”[65]

This citation is straightforward. This means that our earliest known commentator held that John wrote Revelation under Domitian—not Nero.

Yet, early date advocates raise another passage from Victorinus that muddies the waters. Elsewhere, it is argued, Victorinus implies that Paul copied from the book of Revelation—essentially dating the book before Paul’s letters. Victorinus notes that Paul only wrote letters to seven churches (e.g. Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Thessalonica, Philippi, and Colossae). Why did Paul limit his letters to seven? Early date advocates state that Victorinus believed Paul was modelling this practice on Revelation 2-3. If this is the case, then John must have written Revelation before Paul died in AD 67. According to Furlong, “Victorinus may therefore unconsciously betray his use of a source that placed John’s writing before Paul’s.”[66] Here is the key passage from Victorinus:

“In the whole world Paul taught that all the churches are arranged by sevens, that they are called seven, and that the Catholic Church is one… That he himself also might maintain the type of seven churches, he did not exceed that number. But he wrote to the Romans, to the Corinthians, to the Galatians, to the Ephesians, to the Thessalonians, to the Philippians, to the Colossians; afterwards he wrote to individual persons, so as not to exceed the number of seven churches.”[67]

Is Victorinus teaching that Paul copied from the book of Revelation? No. In context, John’s “seven churches” represent the universal church (i.e. “the Catholic Church is one”). Victorinus is claiming that Paul used the same pattern that John used—not that Paul copied from John’s book. The concept that the number “seven” is symbolic for perfection is a very common view, and it doesn’t require Paul to have copied from Revelation. Victorinus is seeing a parallel or a pattern between Paul and John—not a case of plagiarism between Paul and John.

Summary of the External Evidence

The late date of Revelation possesses an absolute avalanche of external evidence, while the early date has little more than a snowball. Indeed, early date proponent F.J.A. Hort wrote, “If external evidence alone could decide, there would be a clear preponderance for Domitian.”[69] Moreover, Hitchcock observes, “The first clear, accepted, unambiguous witness to the Neronic date is a one-line superscription in two Syriac versions of the New Testament in the sixth and seventh centuries. If the Neronic date were the original date of Revelation, one would expect a witness to this fact in Asia Minor, where the book of Revelation originated, and a witness much earlier than the sixth century.”[70]

Comparison of the External Evidence[71] |

|

Domitianic Date |

Neronic Date |

|

Irenaeus (AD 180) |

— |

| Victorinus (AD 300) |

— |

|

Eusebius (AD 340) |

— |

| Jerome (AD 400) De Vir. Illus.9. |

— |

|

Sulpicius Severus (AD 400) |

— |

| Primasius (AD 540) |

Syriac translations of the NT (AD 508)[72] |

|

Isidore of Seville (AD 600) |

— |

| The Acts of John (AD 650) |

— |

|

Orosius (AD 600) |

— |

| Andreas (AD 600) |

— |

|

Venerable Bede (AD 700) |

— |

| — |

Arethas (AD 900) |

|

— |

Theophylact (AD 1107) Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca, 123.1133-1134. |

(2) Internal Evidence

Internal evidence comes from within the document itself. In addition to the external evidence from the church fathers, the book of Revelation has many internal indications that support the late date.[73]

ARGUMENT #1: The late date explains why John, Paul, and Timothy never mention one another together in Ephesus.

If the early date is true, then John would have been leading in Ephesus at the same time as Paul and Timothy. Why would Paul leave Timothy in charge of the Ephesian church if the apostle John was there? Moreover, at the end of 2 Timothy, Paul mentions 17 coworkers by name, but he never mentions John. We are not merely making an argument from silence. This is a conspicuous silence. Why wouldn’t Paul mention such a spiritual titan like John? Likewise, why wouldn’t Jesus mention Paul or Timothy when writing to the church of Ephesus? (Rev. 2:1-7) Witherington writes, “The lack of apostolic presence and, by contrast, the presence of powerful prophets (both John and those he calls false prophets) seem to reflect a time after the apostles had died off late in the first century A.D. (cf. the Didache).”[74]

ARGUMENT #2: The late date explains why Paul and Jesus give conflicting reports about false teachers in Ephesus.

Paul’s letters to Ephesus and Jesus’ letter to Ephesus give conflicting reports regarding false teachers. On the one hand, Paul writes about men who “teach strange doctrines” (1 Tim. 1:3) and the “doctrines of demons” (1 Tim. 4:1). Paul even mentions several false teachers by name: Hymenaeus, Alexander, and Philetus (1 Tim. 1:20; 2 Tim. 2:17). Yet, Jesus’ letter to Ephesus tells a different story. Instead of being riddled with false teachers, Jesus says, “You cannot tolerate evil men, and you put to the test those who call themselves apostles, and they are not, and you found them to be false… You hate the deeds of the Nicolaitans, which I also hate” (Rev. 2:2, 6). This is quite unlike the church of Pergamum who “have some who… hold the teaching of the Nicolaitans” (Rev. 2:15).

ARGUMENT #3: The late date explains how the church in Smyrna had time to grow before receiving a letter from Jesus.

Polycarp wrote a letter to the Philippians in AD 110. In it, he states that the Smyrnaeans weren’t believers when Paul wrote his letter to the Philippians in AD 60-61.

[You Philippians] are praised in the beginning of his Epistle. For concerning you he boasts in all the Churches who then alone had known the Lord, for we had not yet known him.[75]

Polycarp was the bishop of Smyrna. So, his use of the plural “we” refers to “the church at Smyrna,” which would “indicate that that church was not in existence at the time in question.”[76] Put simply, Polycarp is claiming that “when Paul wrote Philippians no Smyrneans had yet been evangelized.”[77]

Craig Blomberg[78] and Gordon Fee[79] date Philippians to AD 61. Therefore, Polycarp maintains that the church in Smyrna didn’t exist before this time. This, of course, carried difficulties for the early date advocate. It requires a church entering Smyrna and springing up all within a 4-5 year span. Acts 19:10 says that “All who lived in Asia heard the word of the Lord,” but this is hyperbolic language. This doesn’t mean that a church specifically existed in the city of Smyrna. Moreover, Paul never mentions a church existing in Smyrna in any of his letters.

ARGUMENT #4: The late date explains how the church in Laodicea had time to plummet spiritually by AD 65.

D.A. Carson, Douglas Moo,[80] and P.T. O’Brien[81] date Colossians to AD 60-61. Paul mentions a thriving church in Laodicea at this time (Col. 2:2; 4:13, 16). However, if Revelation was written in AD 65, then this church must have plummeted spiritually in just a few years. In fact, they had become so bad, that Christ threatened to vomit them out of his mouth! (Rev. 3:16) Of course, spiritual decline can occur quickly (Gal. 1:6), but which is more likely? A quick decline or a slower decline?

ARGUMENT #5: The late date explains Jesus’ words to the church in Laodicea in light of the great earthquake of AD 60.

The entire region around Laodicea suffered a massive earthquake in AD 60. In fact, the region suffered until at least AD 80,[82] and the “archaeological evidence at Laodicea points to a thirty-year rebuilding process.”[83]

And yet, Jesus told the Laodiceans that they are “wealthy” and “have need of nothing” (Rev. 3:16). If the early date is true, it would be quite cruel to tell a destroyed city that they are “wealthy” and “have need of nothing.” However, if the late date is true, this would make perfect sense. Tacitus mentions that the Laodiceans refused all aid from the Roman Empire after the earthquake.[84] They rebuilt their city all on their own, because they were “wealthy” and had “need of nothing.” Hemer writes, “There is good reason for seeing Rev. 3.17 against the background of the boasted afluence [sic] of Laodicea, notoriously exemplified in her refusal of Roman aid and her carrying through a great programme of reconstruction in a spirit of proud independence and ostentatious individual benefaction.”[85]

Conclusion

Not all of these lines of evidence are equally cogent. In other words, some carry more explanatory power than others. But don’t miss the big picture: The late date has more explanatory power and explanatory scope than the early date. We could surely give a number of ad hoc explanations from an early date perspective, but eventually, the early date simply collapses under the weight of the evidence.

Evidence for the Early Date

So far, we have considered evidence in favor of the late date for Revelation. But what about evidence that can be marshalled in favor of the early date? We will conclude by evaluating this evidence as well.

What about the mention of the Temple in Revelation 11?

John speaks about the existence of the Jewish Temple in his book (Rev. 11:1-2). Preterist interpreters argue that John had no knowledge of the destruction of the Jewish Temple (which occurred in AD 70). For this reason (they argue), this book must have been written before AD 70.

First, the predictions in Revelation 11 do not fit the Jewish War of AD 66-70. For one, Revelation 11:13 states that a massive earthquake will strike Jerusalem, and 10% of the population will die. Of course, this is not how the city of Jerusalem was destroyed.

Second, John claims to be writing prophecy—not history. John writes that his book is a work of “prophecy” (Rev. 1:3; 19:10; 22:7, 10, 18-19). Specifically, he claims to know “the things which must soon take place” (Rev. 1:1). For John to write about the past destruction of the Temple would be out of line with the intent of the book. Moreover, Jesus explicitly commands John: “Therefore write the things which you have seen, and the things which are, and the things which will take place after these things” (Rev. 1:19). If John decided to write about the past, then he would be disobeying Jesus’ command.

Third, Ezekiel wrote about a future temple that wasn’t in existence during his day and age. In Ezekiel 40-42, the prophet sees a vision of an angel measuring the Temple of God. However, when Ezekiel wrote this, no Temple existed. Similarly, John saw an angel measure the Temple, but this was a future Temple that wasn’t in existence yet.

Fourth, Daniel wrote about a future temple that wasn’t in existence when he wrote. In Daniel 9:24-27, the prophet wrote of a future Temple that would be destroyed by “the people of the prince who is to come.” However, in Daniel’s time period, no Temple existed. How is this any different than John writing of a future Temple?

Why does John record the history of the destruction of Jerusalem?

Preterists argue that it is bizarre that John would fail to mention the destruction of Jerusalem, if he was writing in AD 95. After all, Jesus’ prediction of the destruction of Jerusalem was an excellent apologetic for supporting the veracity of Christ’s claims. However, a number of counterarguments can be made:

First, the original audience was ethnically and geographically different than Jerusalem. When we look at the churches in Revelation 2 and 3, they are all Gentile churches—not Jewish believers. Moreover, they lived 800 miles from Jerusalem.

Second, the original audience was chronologically different than Jerusalem. If the late date is true, then the destruction of Jerusalem would’ve been 25 years in the past.

Third, John was commanded to write about prophecy (Rev. 1:3)—not apologetics or history. In Revelation 1:19, Jesus commands John: “Therefore write the things which you have seen, and the things which are, and the things which will take place after these things.” John was a prophet who was writing about the future—not a historian or an apologist who was writing about the past. If Revelation was an apologetics text, we might expect him to mention this fulfilled prophecy. However, Revelation is a book of prophecy—not apologetics or history.

Finally, if the destruction of the Temple was supposed to be an incredible apologetic, why doesn’t Revelation predict its destruction? John describes the destruction of Jerusalem in his book, but he never describes the destruction of the Temple. Some argue that the “measuring line” might refer to the Temple’s judgment. Perhaps. But this would be an implicit reference to judgment at best—not an explicit one. For more on the Temple, see comments on Revelation 11:1.

Does Widespread Persecution imply an Early Date?

Early date advocates argue that the descriptions of widespread persecution in Revelation 2-3 imply a date under Emperor Nero who was known for his sadistic torture of Christians.[86] Revelation uses the term “witness” (martus) five times, and each time it refers to a person it involves a violent death (Rev. 1:5; 2:13; 3:14; 11:3; 17:6). Thus, it is argued that this lines up with Nero’s reign. Yet, this evidence lacks weight for several reasons:

Domitian was just as bad as Nero—perhaps worse. That is, Nero didn’t hold a monopoly on sadism or persecution. Suetonius describes Domitian’s final years as a reign of terror (Domitian 8.10). Raymond Brown concedes that this could be somewhat exaggerated; yet he notes that “the names of at least twenty opponents executed by Domitian are preserved.”[87]

Domitian persecuted Christians. In the late first-century (AD 95?), Clement spoke of “sudden and repeated calamities” for Christians (1 Clem. 1:1). In the same letter, he compares the persecution of Peter and Paul with the persecution of believers in his own day. He writes, “We are in the same arena, and the same struggle is before us” (1 Clem. 7:1). Melito of Sardis (2nd c.) states that Domitian slandered and falsely accused Christians.[88] Finally, both Eusebius[89] and Tertullian[90] cite major persecutions under Domitian’s reign.

Pliny the Younger (Epistle 10.96) knew of Christian persecution predating him, and he was writing all the way out in Bithynia in AD 112. He writes that he “does not know how the crime is usually punished.” But he assumed execution was in order. This gives us a window into the punishment for Christians preceding him! Osborne writes, “While no evidence of widespread persecution exists, the relation between the state and Roman religious life put tremendous pressure on all citizens to participate in the official religion. Every aspect of civic life, from the guilds to commerce itself, was affected. Also, Asia Minor was known for its pro-Roman zeal, especially in terms of the imperial cult. Therefore, the relationship of Christians to the imperial cult there was a decisive test, and local persecution was likely.”[91]

Domitian demanded worship. People called Domitian “lord and god” (dominus et deus).[92] Suetonius writes, “With no less arrogance [Domitian] began as follows in issuing a circular letter in the name of his procurators: ‘Our Master and our God bids that this be done.’ And so from then on, the custom arose of addressing him in no other way even in writing or in conversation. He allowed no statues to be set up in his honor in the Capitol, except of gold and silver and of a fixed weight.”[93] Dio Chrysostom wrote that “[Domitian] was called ‘master and god’ by all Greeks and barbarians, but was in reality an evil demon” (Oratio 45.1). Emperor deification goes back as far as Augustus and Caligula. So, this doesn’t help us date the book one way or another. However, Morris does state, “On the score of emperor-worship Domitian’s reign is the most probable by far.”[94]

Therefore, at the very least, this evidence goes both ways. As even early date advocate J.A.T. Robinson writes, “The book of Revelation would fit into what we know of his [Domitian’s] reign.”[95]

The Muratorian Fragment (AD 170)

Early date advocates appeal to the Muratorian Fragment which dates to around AD 170 in Rome. This document states that Paul was copying the pattern of John by only writing to seven churches (e.g. Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Thessalonica, Philippi, and Colossae). But if Paul was copying John’s pattern, then this would date Revelation before Paul’s letters. The Muratorian Fragment states:

“The blessed apostle Paul himself, following the example of his predecessor John, writes by name to only seven churches in the following sequence: To the Corinthians first, to the Ephesians second, to the Philippians third, to the Colossians fourth, to the Galatians fifth, to the Thessalonians sixth, to the Romans seventh. It is true that he writes once more to the Corinthians and to the Thessalonians for the sake of admonition, yet it is clearly recognizable that there is one Church spread throughout the whole extent of the earth. For John also in the Apocalypse, though he writes to seven churches, nevertheless speaks to all. [Paul also wrote] out of affection and love one to Philemon, one to Titus, and two to Timothy; and these are held sacred in the esteem of the Church catholic for the regulation of ecclesiastical discipline.”

Does this support an early dating of Revelation? In our estimation, this statement must be historically inaccurate—for this would make the book of Revelation the first book written in the NT! It stretches our credulity to think that a Christian Apocalypse was written before all Four Gospels, Acts, and the various epistles. After all, Galatians dates to AD 48 according to D.A. Carson, Douglas Moo,[96] and Ronald Fung.[97] Moreover, 1 and 2 Thessalonians date to AD 50-51 according to F.F. Bruce,[98] Craig Blomberg,[99] and Robert Thomas.[100] Do we honestly believe that Revelation dates to the 40’s AD? Early date advocates do themselves no favors by citing this as evidence of an early date. This doesn’t support an early date; it supports an erroneous date.

Furthermore, the Muratorian Fragment gets the order of the letters wrong. The fragment states that Paul wrote to the “seven churches in the following sequence.” However, it places the letters out of order. As we’ve already seen, Galatians and Thessalonians were written first—not “fifth” and “sixth.” Moreover, Ephesians, Philippians, and Colossians were written while Paul was in prison at the end of his life in the early AD 60s—not “second,” “third,” and “forth.” Our best guess is that the Muratorian Fragment was trying to show that Paul was using a similar pattern to John—not that Paul was plagiarizing John.

Irenaeus (AD 180)

When were the Nicolaitans around? Hippolytus (of Portus?) claimed that Nicolas taught “Hymenaeus and Philetus,” the heretics whom Paul encountered (2 Tim. 2:16-17).[101] This would date the Nicolaitan heresy to the time of Paul (~AD 67) and Nero. More importantly, Irenaeus states that the Nicolaitans were active “a long time previously”[102] to Cerinthus. Furlong takes the words “long time” (multo prius) to “indicate a period of decades.”[103] Moreover, Furlong adds, “Irenaeus seems to envision the Nicolaitans as no longer active at the time that Cerinthus was spreading his teaching.”[104]

When did Cerinthus live? Irenaeus places Cerinthus at the end of the first century. John was with Polycarp and refused to enter the public baths when Cerinthus was there.[105] Since Polycarp was there, this must date to “the end of the first century.”[106]

How long did the Nicolaitans exist? Eusebius states that the Nicolaitans “existed for a very short time.”[107] Thus, this heresy couldn’t have lasted much longer than Nero reign. Yet, Jesus refers to the Nicolaitans when he addresses the churches at Ephesus and Pergamum (Rev. 2:6, 15). This implies that John wrote Revelation in the AD 60s. But a couple of counterarguments can be raised.

First, if one of these sources is wrong, the entire theory collapses. For instance, if the dating of the Nicolaitans is wrong, then the theory collapses. If the idea that they only existed for a short time is wrong, then the theory collapses. If the time indicators are being misread (“a very short time” or “a long time previously”), then the theory collapses. Quite frankly, this abductive argument is only as strong as its weakest link. If I was an early date advocate, I would use this argument with caution.

Second, Eusebius places Cerinthus and the Nicolaitans in the same time period. After recounting John fleeing the bathhouse of Cerinthus, Eusebius writes,

“At this time, also, there existed for a very short time the so-called heresy of the Nicolaitans of which the Apocalypse of John makes mention. These boasted of Nicolaus, one of the deacons with Stephen chosen by the Apostles for the service to the poor.”[108]

Eusebius places the Nicolaitans at the time of Cerinthus at the end of the first century. Honestly, this one passage brings the entire theory crashing down.

Third, the Church Fathers are conflicted on the subject of the Nicolaitans. The great historian Philip Schaff writes, “The views of the fathers are conflicting.”[109] Consider two crucial conflicts that face the historian:

- Irenaeus believed Nicolas was the founder of the heretical sect of Nicolaitans.[110] On the other hand, Clement of Alexandria states that Nicolas was a faithful husband and good father. The apostles accused him of being a jealous husband, and he offered to give his wife away.[111]

- Hippolytus,[112] Irenaeus,[113] and Eusebius[114] believed that the Nicolaitans originated from “Nicolaus” (or “Nicanor”), who was one of the seven deacons chosen to distribute food to the widows (Acts 6:5). But Ignatius[115] didn’t believe that the Nicolaitans came from Nicanor.

How do we make sense of these accounts? More importantly, how much trust should we place in an abductive case drawn from these multiple conflicting traditions?

Tertullian (AD 200)

Tertullian was the first to talk about the boiling oil and exile.[116] Jerome claimed that Nero was the one to place John in boiling oil.[117] Then, Jerome states that John was sent “immediately” to Patmos after being dunked in the oil (Commentary on Matthew, 20.23). Early date advocates argue that the translation switched from “by Nero” to “at Rome” by Vittori in 1564.[118] Consequently, “Jerome… attributed to Tertullian a Nerorian setting for the boiling oil legend.”[119] However, many problems face this evidence:

First, Tertullian didn’t affirm this. In fact, “There is no extant text of Tertullian that relates this.”[120] These “sources which are no longer extant.”[121]

Second, Jerome accepted the Domitianic banishment. He claimed elsewhere that John was exiled under Domitian.[122] To salvage this perspective, early date advocates argue that perhaps “Jerome may have known another version of the story from one of Tertullian’s lost works, with which he is known to have been familiar.”[123]

Third, the account of the boiling oil seems to be a case of legendary embellishment. Tertullian’s statement itself already seems legendary at best.[124] But Jerome adds details to Tertullian’s account. He states that John entered a “terracotta jar” (dolium), and he came out “cleaner and more vigorous than when he entered.” This could be an example of hagiography, where Christians had a tendency to embellish accounts of the apostles. Moreover, the story itself is hard to believe.

Finally, even if all of this were true, John still could’ve seen the vision in AD 95! It might seem like a stretch to think that John would be exiled for 30 years, but why would we think this? Imperial edicts weren’t always rescinded, and even John entered exile under Nero, it’s quite possible he stayed into Domitian’s reign.

Clement of Alexandria (AD 215)

Early date advocates offer another passage from Clement to argue for a Neronic date. From this passage, they infer that the NT canon was closed during the reign of Nero. Clement of Alexandria writes:

“[The teaching] of the apostles, embracing the ministry of Paul, ends with Nero” (Stromata 7.17).

Of course, Nero reigned from AD 54-68. This would imply that John couldn’t have written Revelation after Nero’s death in AD 68. But not so fast. There are a number of problems with taking this inference from the text:

First, according to our earlier text, John clearly continued to serve Christ after “the death of the tyrant.” Even if the tyrant was Nero, then John couldn’t have continued to teach and plant churches.

Second, because of John’s banishment to Patmos, he was unable to “teach” as Clement asserts. However, Clement says nothing about a writing ministry on the island of Patmos. Yet this is precisely the debate at hand: When did John write Revelation? Even if the teaching of the apostles ended in AD 68, this wouldn’t mean that John also stopped writing Scripture also.

Third, instead of writing, “[The teaching] of the apostles… ends with Nero,” Clement adds the curious expression, “[The teaching] of the apostles, embracing the ministry of Paul, ends with Nero.” What does this statement mean? And why does he include it? In our estimation, Clement is not referring to all of the apostles, but only those who worked closely with Paul. This would make sense of the historical data. After all, Peter and James worked closely with Paul (Gal. 1:18-19; 2:9; Acts 15:7-13; 21:18), and Peter and James died under Nero’s reign (1 Clement 5:4-5; Antiquities 20.197). John, however, didn’t work closely with Paul. In fact, there is only one instance of Paul and John meeting in the NT (Gal. 2:9). It seems to be the case that Clement is only referring to the apostles who knew Paul well.

John’s old age joy ride

Early date proponents cite another story to support their case. Clement of Alexandria tells a story that took place after John was released from exile.[125] In Clement’s account, John travelled to a city near Ephesus. Here, John led a young man to Christ, and left him under the care of the local bishop. Yet, the young man apostatized and fell in with a gang of robbers. Once John heard the news, he got on a horse and chased down the young man to bring him back to following Christ. Early date advocates argue that these events took place over a long period of time: “The temporal markers used by Clement in the account do not give an impression that these events were conceived of as having unfolded rapidly.”[126]

Early date advocates have a hard time believing that an old man like John could leave exile in AD 95 only to continue to have an extraordinary horse chase in the mountains over a period of years. This especially doesn’t fit with Jerome’s comments that John needed to be carried into the church in his old age, and could hard find breath to speak.[127] In response, we would make a number of observations.

First, Clement alludes to the fact that John is very old. When he describes the horse chase, Clement writes that John was “forgetting his age,” and he refers to John as an “old man.”

Second, Clement might imply a long passage of time, but he simply doesn’t tell us how much time passed. We need to do better than this if we’re going to use this as an argument for dating a book.

Third, a single convert can apostatize quickly, and apostates can also be restored quickly as well (e.g. Peter). Early date advocates appeal to this line of reasoning when discussing the fall of the Laodicean church as well as the creation of the Smyrnean church (see above). But if entire churches can rise and fall in a short period of time, then why can’t a single convert?

Fourth, Eusebius states that Clement’s “tyrant” was “Domitian.”[128]

Athanasius (AD 367)

Some early date advocates[129] argue that Athanasius believed the canon was closed by AD 70. Athanasius writes,

“When did prophet and vision cease from Israel? Was it not when Christ came, the Holy One of holies? …Once the Holy One of holies had come, both vision and prophecy were sealed. And the kingdom of Jerusalem ceased at the same time.”[130]

There are many problems with this historical argument:

For one, this isn’t a historical argument. This is Athanasius’ theological view and his interpretation of Daniel 9:24. Yet, this doesn’t claim to be historical tradition whatsoever.

Second, Athanasius doesn’t mention the NT canon. He seems to be referring to OT revelation. Athanasius writes, “Jerusalem no longer stands, neither is prophet raised up nor vision revealed among them. And it is natural that it should be so, for when He that was signified had come, what need was there any longer of any to signify Him? And when the Truth had come, what further need was there of the shadow?” These are all allusions to OT revelation (Heb. 10:5), not the writing of NT Scripture. Thomas writes, “Careful scrutiny of the Athanasius quotation, his comment on Gabriel’s words in Dan. 9:24, reflects that Chilton’s interpretation of it is quite forced. Athanasius at that point did not address the issue of the NT canon at all.”[131]

Third, Athanasius doesn’t give a clear and singular date of AD 70. Prophecy and vision are said to cease when Jesus came (AD 33) and when Jerusalem was destroyed (AD 70). He doesn’t firmly land on one date or another.

Further Resources

Hitchcock, Mark. “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Found here.

Hank Hanegraff versus Mark Hitchcock Debate: The Date of Revelation.

James Rochford versus Dr. Dean Furlong Debate: “The Book of Revelation: Written Early or Late?”

Hitchcock, Mark. “A Critique of the Preterist View of Revelation and the Jewish War.” Bibliotheca Sacra 164 (January-March) 2007. 89-100.

Hitchcock, Mark. “A Critique of the Preterist View of Revelation 17:9-11.” Bibliotheca Sacra 164 (October-December) 2007: 472-485.

Hitchcock, Mark. “A Critique of the Preterist View of the Temple in Revelation 11:1-2.” Bibliotheca Sacra 164 (April-June 2007): 219-236.

[1] Kenneth L. Gentry, “The Days of Vengeance: A Review Article,” The Counsel of Chalcedon, Vol. IX, No. 4., p. 11.

[2] Emphasis his. Kenneth L. Gentry, The Beast of Revelation (Tyler, TX: Dominion Press, 1994), 86.

[3] R.C. Sproul, The Last Days According to Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1998), p.140.

[4] David Chilton, The Days of Vengeance: An Exposition of the Book of Revelation (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion, 1987), 3-6.

[5] Zane Hodges, Power to Make War (Dallas: Redencion Viva, 1995).

[6] Grant Osborne, Revelation: Baker Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), p.6.

[7] D.A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament (Second ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), p.707.

[8] Mitchell Reddish, Revelation: Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2001), p.16.

[9] G.K. Beale, The Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), p.4.

[10] Colin J. Hemer, The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia in their Local Setting (England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1989), p.3, 5.

[11] Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament (New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1997), p.805.

[12] Mark Allan Powell, Introducing the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009), p.531, 532.

[13] Alan Johnson, Revelation: The Expositor’s Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1981), p.406.

[14] Craig Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), in loc.

[15] Steve Gregg, Revelation, Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (Nashville, TN: T. Nelson Publishers, 1997), p.15.

[16] Donald Guthrie, New Testament Introduction (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1990), p.948, 962.

[17] David Aune, Revelation 1-5: Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1997), lvii.

[18] Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1997), p.21.

[19] Irenaeus, Against Heresies 4.14.1-8; 5.33.4. Letter to Florinus. Irenaeus writes, “I can remember the events of that time… so that I am able to describe the very place where the blessed Polycarp sat… and the accounts he gave of his conversation with John and with others who had seen the Lord” (Irenaeus as quoted by Eusebius, Church History 5.20.5-6).

[20] Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.3.4.

[21] Steve Gregg, Revelation, Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (Nashville, TN: T. Nelson Publishers, 1997), p.17.

[22] Irenaeus as quoted by Eusebius, Church History 5.20.5-6).

[23] As a side note, Irenaeus considers three people who might possibly fulfill the “666” of Revelation 13:18 (e.g. Euanthas, Lateinos and Teitan). Lateinos would refer to the Roman Empire—past, present, and future. Yet he never even considers Nero as the fulfillment. If the “666” (or “616”) refers to Nero, as Preterists so confidently claim, then why doesn’t Irenaeus affirm this? For that matter, why doesn’t any other ancient Church Father affirm this?

[24] Eusebius of Caesaria, “The Church History of Eusebius,” in Eusebius: Church History, Life of Constantine the Great, and Oration in Praise of Constantine, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. Arthur Cushman McGiffert, vol. 1, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1890), 148.

[25] Translated by Roy Joseph Deferrari, vol. 19, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1953), 165.

[26] Paul L. Maier (translation and commentary), Eusebius: The Church History (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel: 2011).

[27] Translated by Alexander Roberts in James Donaldson and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 559-560.

[28] Translated by Philip Schaff. Against Heresies 5.30 (Roman Roads Media), 168.

[29] We are greatly indebted to Mark Hitchcock for many of these arguments. See Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), pp.24-28.

[30] This isn’t an unbreakable rule of hermeneutics. But the person who seeks to break this rule shoulders the burden of proof.

[31] Paul L. Maier (translation and commentary), Eusebius: The Church History (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel: 2011).

[32] Paul L. Maier (translation and commentary), Eusebius: The Church History (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel: 2011).

[33] See also Eusebius, Church History 3.23.3.

[34] See translations of Eusebius, Church History by Christian Frederick Cruse (1850), Arthur Cushman McGiffert (1890), Kirsopp Lake (1908), Roy Joseph Deferrari (1953), Paul L. Maier (2011), and Jeremy M. Schott (2019).

[35] Johannes J. Wetstein, Nouum Testamentum Graecum, vol. 2 (1751), 746. Cited in Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.105.

[36] John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1976, 2000), p.221.

[37] David Aune, Revelation 1-5: Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1997), lix.

[38] G.K. Beale, The Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), p.20.

[39] Irenaeus, Against Heresies 2.22.5-6.

[40] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.33.

[41] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.33.

[42] Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: C. Scribner’s, 1907), 2:750-751.

[43] John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1976, 2000), p.221.

[44] Hanegraaff writes that Irenaeus sheds “significant light on the historical accuracy of the New Testament.” Hank Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis: 21st Century (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2009), 337.

[45] Hanegraaff follows Gentry in challenging the “credibility” of Irenaeus, because “in the same volume [Irenaeus] contends that Jesus was crucified when he was about fifty years old.” Hank Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2007), 153.

[46] Kenneth Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell: Dating the Book of Revelation (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1989), 66.

[47] Emphasis mine. Kenneth Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell: Dating the Book of Revelation (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1989), 62-63.

[48] Eusebius, Church History, 3:39.

[49] Eusebius, Church History, 3:24:17-18; 5:8:5-7; 7:25:7-8, 14.

[50] Clement of Alexandria, Who is the Rich Man that Shall Be Saved? 42.

[51] Eusebius, Church History 3.23.5-19.

[52] Tertullian, The Prescription Against Heretics 36.3.

[53] See 1 Clement 5:4-5; Tertullian, Ecclesiastical History, 2:25.5; Caius & Dionysius of Corinth, 2:25.8.

[54] Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

[55] See 1 Clement 5:4-5; Tertullian, Ecclesiastical History, 2:25.5; Caius & Dionysius of Corinth, 2:25.8.

[56] Dio Cassius, Roman History 67.3, 13, 14.

[57] Dio Cassius, Roman History 67.3.3, 13.3, 14.3, 14.4.

[58] Dio Cassius, Roman History 67.14.2.

[59] Athenagoras, Legatio pro Christianis, 3. The Martyrdom of Polycarp 3, 9. Justin Martyr, First Apology 6, 13.

[60] Eusebius, Church History 3.18.4.

[61] G.K. Beale, The Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), p.8.

[62] Craig Blomberg, From Pentecost to Patmos: An Introduction to Acts through Revelation (Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2006), p.510.

[63] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.20.7-8; 3.32.1.

[64] Jerome, Against Jovinianus 1.26.

[65] Victorinus, Apocalypse 10:11.

[66] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.64.

[67] Victorinus, Apocalypse 1.7.

[68] Sean McDowell, The Fate of the Apostles (New York: Routledge, 2016), p.144.

[69] F.J.A. Hort, The Apocalypse of John: I-III (MacMillan and Company, 1908), xx.

[70] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.74.

[71] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.73.

[72] Koester dates these to the fourth century. Craig Koester, Revelation: The Anchor Yale Bible (Yale University Press, 2014), p.72.

[73] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.177.

[74] Ben Witherington III, Revelation: The New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge University Press, 2003), p.4.

[75] Polycarp, Letter to the Philippians 11.3.

[76] See footnote. Leon Morris, Revelation: Tyndale Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1987), p.41.

[77] David Aune, Revelation 1-5: Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1997), lviii.

[78] Craig Blomberg, From Pentecost to Patmos: An Introduction to Acts through Revelation (Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2006), p.326.

[79] Gordon D. Fee, Philippians, vol. 11, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series (Westmont, IL: IVP Academic, 1999), p.12.

[80] D.A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 522.

[81] Peter T. O’Brien, Colossians, Philemon, vol. 44, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1982), liv.

[82] Sibylline Oracles 4.107-108.

[83] Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary (December 2005), p.187.

[84] Tacitus, Annals 14.27.1.

[85] Colin J. Hemer, The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia in their Local Setting (England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1989), p.195.

[86] Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

[87] Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament (New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1997), p.806.

[88] Eusebius, Church History 4.26.9.

[89] Eusebius, Church History 3.17, 20 (citing Hegesippus and Tertullian); 4.26 (citing Melito of Sardis).

[90] Tertullian, Apologia 5.

[91] Grant Osborne, Revelation: Baker Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), p.8.

[92] Suetonius, Domitian, 13:2-3; Martial, Epigrams 9.56.3; Dio Cassius, History, 67.4.7.

[93] Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, “Domitian” 13.

[94] Leon Morris, Revelation: Tyndale Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1987), p.39.

[95] John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1976, 2000), p.236.

[96] D.A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament (Second ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), p.464.

[97] Ronald Y. K. Fung, The Epistle to the Galatians, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1988), 28.

[98] F. F. Bruce, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, vol. 45, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1982), xxi.

[99] Craig Blomberg, From Pentecost to Patmos: An Introduction to Acts through Revelation (Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2006), 140.

[100] Robert L. Thomas, “1 Thessalonians,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Ephesians through Philemon, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 11 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1981), 232.

[101] Hippolytus, De resurr. fr. 1.

[102] Against Heresies, 3.11.1.

[103] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.109.

[104] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.110.

[105] Against Heresies, 3.3.4. cf. Church History, 3.28; 4.14.

[106] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.110.

[107] Church History, 3.29.1.

[108] Church History, 3.29.1.

[109] Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: C. Scribner’s, 1907), 2:464.

[110] Against Heresies, 1.26.3; 3.11.1.

[111] Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 3.4. Philip Schaff considers this account of Nicolas offering to give his wife away to be “extremely improbable.” (see footnote)

[112] Hippolytus, The Refutation of All Heresy, 7.24.

[113] Against Heresies, 1.26.3; 3.11.1.

[114] Church History, 3.29.1.

[115] Ignatius writes, “Flee also the impure Nicolaitanes, falsely so called.” (To the Trallians, 11). The footnote states, “It seems to be here denied that Nicolas was the founder of this school of heretics.”

[116] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.110.

[117] Jerome, Against Jovinianus 1.26.

[118] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.111.

[119] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.110.

[120] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.111.

[121] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.111.

[122] Jerome, On Illustrious Men, 9.6-7.

[123] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.111.

[124] Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1997), 55.

[125] Who is the Rich Man that Shall Be Saved? 42.

[126] Dean Furlong, The Identity of John the Evangelist: Revision and Reinterpretation in Early Christians Sources (Lanham, MD: Fortress Academic, 2020), p.113.

[127] Jerome, Commentary on Galatians, 6.10.

[128] Eusebius, Church History, 3.23.5.

[129] David Chilton, The Days of Vengeance, an Exposition of the Book of Revelation (Fort Worth, Tex.: Dominion, 1987), pp.5-6.

[130] Athanasius, On the Incarnation 6.40. Sister Penelope Lawson, Trans. (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1946), pp. 61ff.

[131] Robert L. Thomas, Revelation 1-7: An Exegetical Commentary (Chicago: Moody, 1992), p.21.