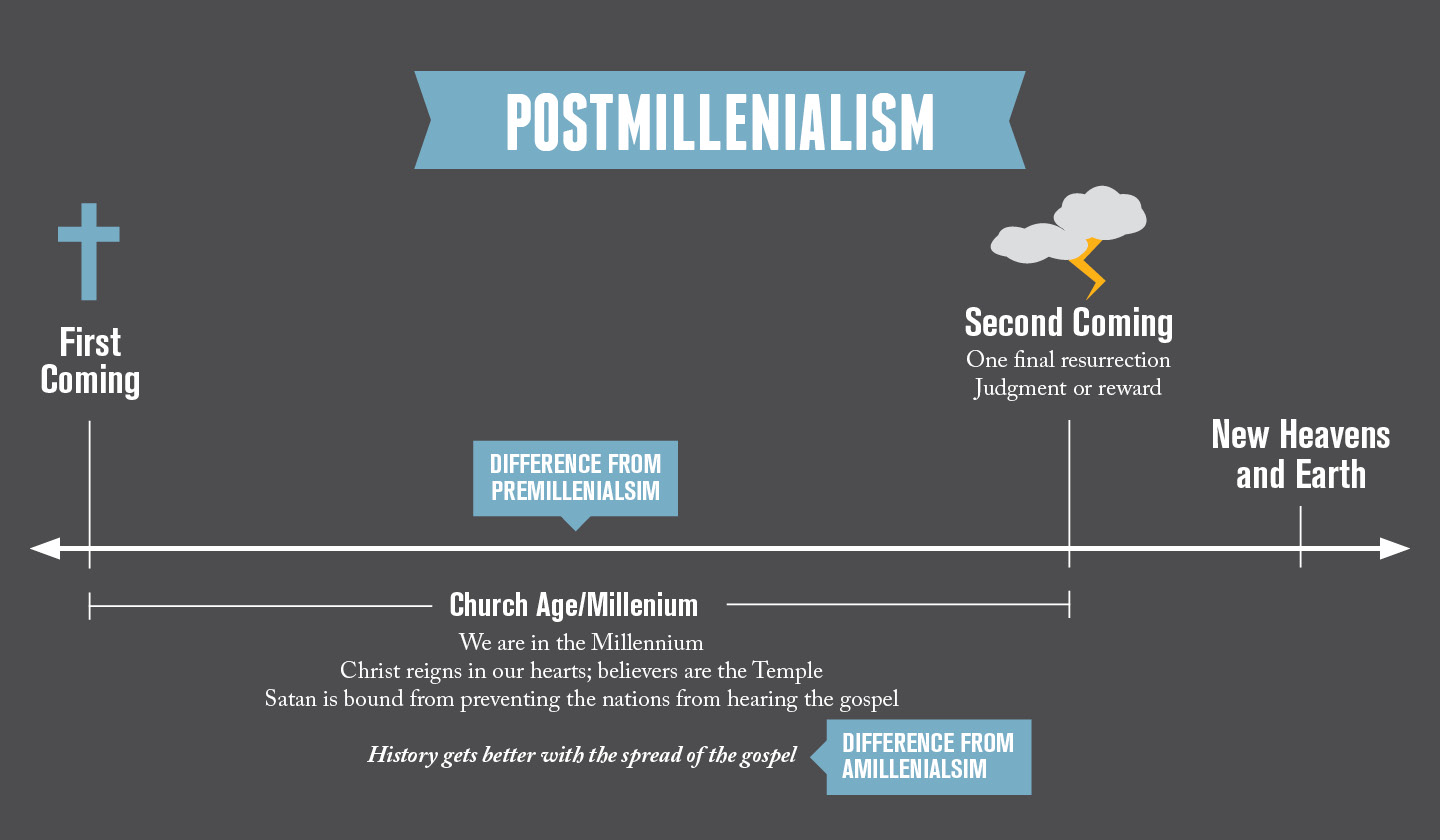

Theologians of various stripes believe that Daniel Whitby (1638-1726) was the first to fully articulate the postmillennial view. Whitby—a Unitarian minister—held that the Church would bring in the return of Christ at the end of the millennium, by Christianizing the world. Postmillennials are similar to amillennials in that they believe in a symbolic millennium. Also, postmillennialists hold that Jesus reigns from heaven or in the hearts of believers on Earth. Postmillennialist James Snowden explains, “The sense, however, in which it is commonly used is the rule of God in the hearts of obedient souls. It is a general designation for all those in all ages who turn to God in faith and constitute the total society of the redeemed.”[1] Postmillennialists believe that the picture of Jesus on the horse in Revelation 19 is a picture of Jesus conquering the nations in the present age. Postmillennialists differ from amillennials in that they believe history will gradually get better until Christ returns, as the world is Christianized. We might define this perspective by its comparison to the others:

Millennial Views |

||||

VIEW |

Premillennial |

Amillennial |

Postmillennial |

Historical Premillennial |

|

The Millennium |

A literal 1,000 year period |

A figurative number |

A figurative number |

A literal 1,000 year period |

|

Christ’s reign |

Reigns literally in a kingdom on Earth after his Second Coming |

Reigns spiritually on a heavenly throne or reigns spiritually in the hearts of believers |

Reigns spiritually in the hearts of believers, as the gospel transforms the nations of the Earth |

Reigns literally in a kingdom on Earth after his Second Coming |

|

Israel |

Christ reigns in Israel over a regathered Israel |

The Church replaces the promises given to national Israel |

The Church replaces the promises given to national Israel |

The Church replaces the promises given to national Israel |

|

View of Human History |

Believes human history will get progressively worse, as the gospel reaches all nations |

Believes human history will get progressively worse, as the gospel reaches all nations |

Believes that human history will get progressively better. The nations will eventually be transformed by Christ’s reign in society |

Believes human history will get progressively worse, as the gospel reaches all nations |

Critique of Postmillennialism

Let’s consider a few arguments against postmillennialism:

ARGUMENT #1: Postmillennialism had no supporters until the 17th century.

We do not feel that this is an overwhelming argument against postmillennialism, because church history is fraught with faulty doctrines. Age does not determine truth. Some heresies are old; other truths can be new. However, as pointed out above, postmillennialism really began in the late 17th century with Daniel Whitby.

Some postmillennials (like Kenneth Gentry) have tried a historical reconstruction that would have many in church history holding to this view. He argues that Athanasius, Augustine, Calvin, and other great theologians held to this view. Let’s consider each:

Athanasius: Amillennial Robert Strimple writes, “The documentation cited for Athanasius in Gentry’s earlier book, He Shall Have Dominion, consists entirely of statements by Athanasius showing that ‘the great progress of the gospel is expected.’ On the basis of that criterion virtually every Christian theologian could be claimed as a postmillennialist!”[2]

Augustine: Augustine should be classified as amillennial—not postmillennial. We agree with Walvoord—contra Gentry—when he writes, “Augustine (354-430) also believed in the coming of Christ after the millennium and could for this reason be classified as postmillennial. His view of the millennium, however, was so removed from a literal kingdom on earth that it is virtually a denial of it, and he is better considered as an amillennialist.”[3]

Calvin: Postmillennial Kenneth Gentry argues that John Calvin held to postmillennial theology, citing Calvin’s Institutes (1:12).[4] However, upon closer inspection, this isn’t the case. However, Strimple firmly disagrees with this,[5] citing the Second Helvetic Confession (1566), which represents Calvin’s teaching (article 11): “We further condemn Jewish dreams that there will be a golden age on earth before the Day of Judgment, and that the pious, having subdued all their godless enemies, will possess all the kingdoms of the earth.”

There is no early representation of postmillennialism in church history: Walvoord writes, “There is no trace of anything in the church which could be classified as postmillennialism in the first two or three centuries. The millenarianism of the early church was premillennial, that is, it expected the return of Christ before a millennium on earth.”[6]

ARGUMENT #2: Both biblically and observationally, we see that human history will get worse—not better.

Jesus uses the most lurid language to describe the decay of human society and suffering toward the end of human history. He states that there will be wars (Mt. 24:6-7), plagues and famines (Mt. 24:7), believers will be persecuted (Mt. 24:9), false religion will increase (Mt. 24:4-5, 11), and lawlessness will increase (Mt. 24:12). Paul writes that in the “last days” people will continue to become more and more selfish, greedy, and evil (2 Tim. 3:1-5). None of this fits with the postmillennial view.

To avoid these clear biblical teachings, postmillennials are often preterists, too. Preterists hold that almost all of these prophecies refer to the period right before the destruction of Jerusalem. However, we do not find this view persuasive either (see “A Critique of Preterism”).

In addition to the biblical data, human history shows no sign of becoming less evil, even as the gospel has been progressing into all nations (Mt. 24:14). This past century, we saw more bloodshed, war, torture, and hatred than any century before it. As theologian Craig Blaising asks, “After almost two thousand years, should we not be able to see this progress?”[7] Thus on both counts—biblically and observationally—we hold that this tenet of postmillennialism is false.

ARGUMENT #3: Because the gospel will change the world, we should utilize biblical law in society (e.g. theonomy or theonomic ethics).

This perspective holds that the Mosaic law is operative for believers and society. Postmillennialist Kenneth Gentry explains, “The judicial-political outlook of Reconstructionism includes the application of those justice-defining directives contained in the Old Testament legislation, when properly interpreted, adapted to new covenant conditions, and relevantly applied.”[8]

However, we strongly reject this view. The law was given to Israel—not to all Christians (Ex. 20:2). We are also not under law, as Christians (Rom. 6:14; 7:6; Gal. 5:1-4; Heb. 7:12). Moreover, the NT contains no prescriptions whatsoever for ruling a society. Of course, as Christians, our faith will influence our decision-making as law makers and citizens, but we are repeatedly told to submit to government—not take it over (Rom. 13:1-7), as Jesus modeled for us (Jn. 6:15; 18:36-37). As we have argued earlier (“Tips for Interpreting OT Law”), the OT law is not operative for believers today, and we certainly shouldn’t spread a theocracy today either. This wasn’t the practice of the apostles or the early church—nor should it be for us as Christians today.

ARGUMENT #4: The Church will bring about world peace through the spreading of the gospel.

As Christians, our hope is not in our work to change the world, but instead, it is in Christ’s Second Coming (1 Thess. 1:9-10; Titus 2:12-13; Heb. 9:28; Jas. 5:7; 1 Pet. 1:13; 2 Pet. 3:11-12). However, the postmillennialist seems to place the believer’s hope in the Church, rather than Christ at his coming.

Biblical Passages that Support Postmillennialism

As amillennialist Robert Strimple has argued,[9] there are a surprisingly few NT Scriptures to support the postmillennial view.

Further Reading from a Postmillennial Perspective

Mounce, Robert H. The Book of Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977.

Boettner, Lorainne. The Millennium. Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1958.

Gentry, Kenneth. “Postmillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999.

[1] James H. Snowden, The Coming of the Lord (New York: Macmillan Company, 1919), p. 184. Cited in Walvoord, John F. The Millennial Kingdom. Findlay, OH: Dunham Pub., 1959. 26.

[2] Strimple, Robert. “Amillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 68.

[3] Walvoord, John F. The Millennial Kingdom. Findlay, OH: Dunham Pub., 1959. 8.

[4] Gentry, Kenneth. “Postmillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 17.

[5] Strimple, Robert. “Amillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 68.

[6] Walvoord, John F. The Millennial Kingdom. Findlay, OH: Dunham Pub., 1959. 19.

[7] Blaising, Craig “Premillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 75.

[8] Gentry, Kenneth. “Postmillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 19.

[9] Blaising, Craig “Premillennialism.” Bock, Darrell (General Editor). Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan. 1999. 69.