Church polity refers to the government of the church (e.g. “political” or “politics”). How should the church be governed? Should we have leaders over the church, and if so, what should be their limits to authority? This subject is incredibly important because of the fact that God’s work could be hindered or encouraged depending on where we stand on this subject. Church polity is generally conceived of in three separate models: (1) Episcopal, (2) Presbyterian, and (3) Congregational.

Church polity refers to the government of the church (e.g. “political” or “politics”). How should the church be governed? Should we have leaders over the church, and if so, what should be their limits to authority? This subject is incredibly important because of the fact that God’s work could be hindered or encouraged depending on where we stand on this subject. Church polity is generally conceived of in three separate models: (1) Episcopal, (2) Presbyterian, and (3) Congregational.

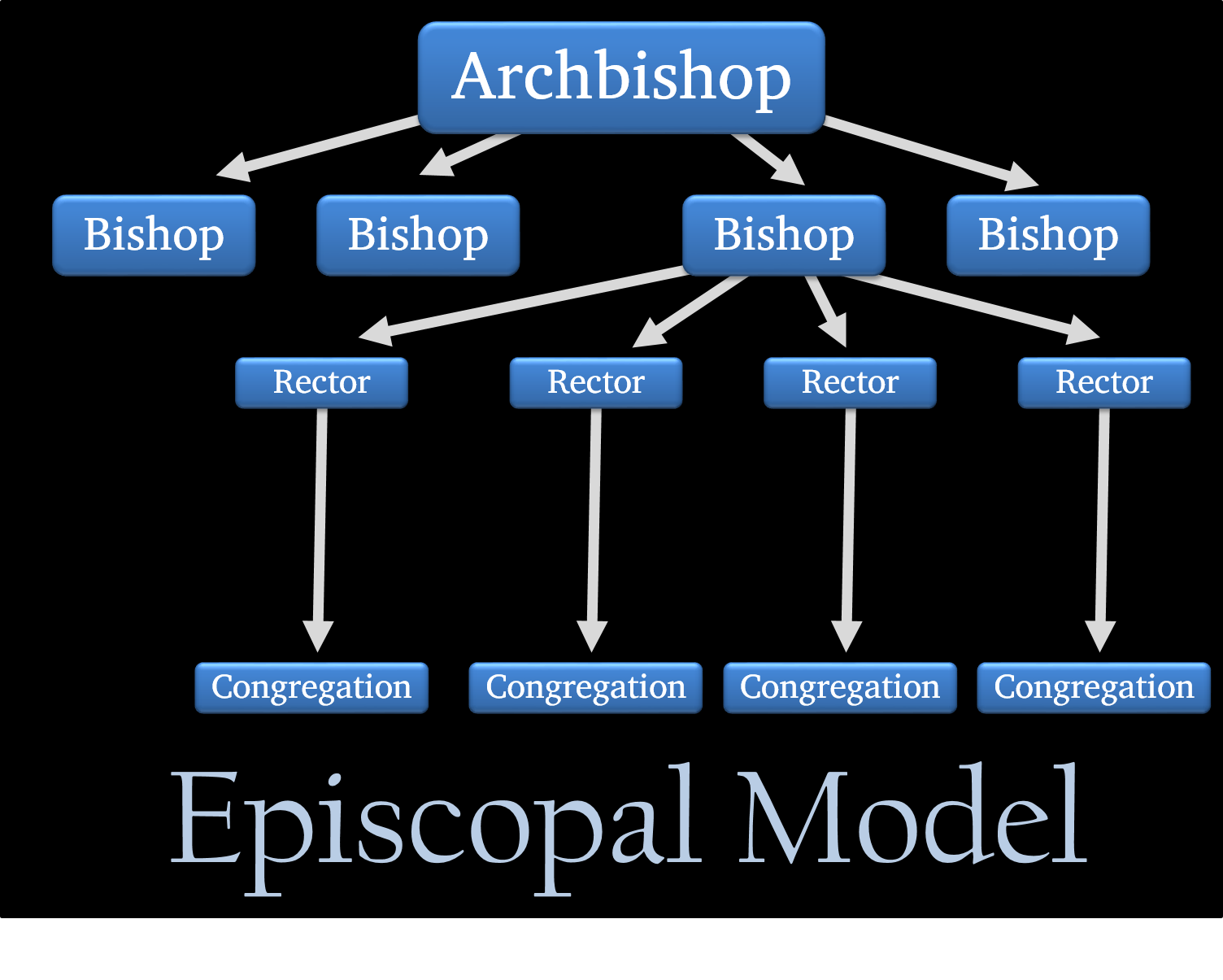

1. Episcopal Model

What is it? This model is also called the Hierarchical model. This model takes its name from the Greek episkopos, which is translated “overseer” or “bishop.” Under this view, the bishops have a diocese, in which they make decisions about who will be leaders in the church. Under this view, the Pope (in Roman Catholicism) or Metropolitan (in the Orthodox Church) rule over the bishops of the various dioceses. Thus an extralocal authority leads individual churches.

Who uses it? This model is used by the Episcopal, Anglican, Catholic, Orthodox, and Methodist churches. Erickson writes, “The simplest form of episcopal government is found in the Methodist Church… Somewhat more developed is the governmental structure of the Anglican or Episcopal Church, while the Roman Catholic Church has the most complete system of hierarchy.”[1]

What is their biblical basis? This model is not directly stated in the NT. For instance, E.A. Litton writes, “No order of Diocesan Bishops appears in the New Testament.”[2] However, advocates of this view note that it is never explicitly banned in the NT either. Moreover, the church historically used this model in the centuries after the apostolic era. It is based on apostolic authority—whereby the apostles had authority to order local churches what to do. For instance, Paul commanded the church in Corinth to remove one of its members for unrepentant sin (1 Cor. 5:3-5). He writes, “I adjure you by the Lord to have this letter read to all the brethren” (1 Thess. 5:27), and “The things which I write to you are the Lord’s commandment” (1 Cor. 14:37). Note that Paul felt that he had command authority, and he didn’t feel that he needed to take a vote or ask for a majority vote to make these decisions.

Strengths? The Episcopal model has the advantage of exerting a good level of control over false teaching. It also expedites decision-making in the church—whereby the leadership could simply make a ruling, rather than ruling through committee. Committees often disagree, making change slow and painful.

Weaknesses? There are many weaknesses in this model:

First, this model doesn’t have accountability at the top of the chain of command. Who watches the watchmen—under this view?

Second, it encourages a clergy-laity distinction. The people in local churches cannot make big ministry decisions without leadership approval or directions from above.

Third, there is no such thing as a bishop who rules over the elders of churches in the NT. Instead, elders and bishops are synonymous. For instance, Luke writes that Paul called together “the elders of the church” (Acts 20:17), but later, Paul says that God had made these same people “overseers to shepherd the church of God” (v.28). Likewise, Paul wanted “elders in every city” (Titus 1:5), but then writes that the “overseer must be above reproach” (Titus 1:7). These terms were used interchangeably.

Fourth, there is no continuity of the apostles laying hands on bishops from the second century church. The members of the church in Antioch laid hands on Paul and Barnabas—not the apostles (Acts 14:3). Likewise, Timothy was not recognized by the apostles, but by a group of elders (1 Tim. 4:14).

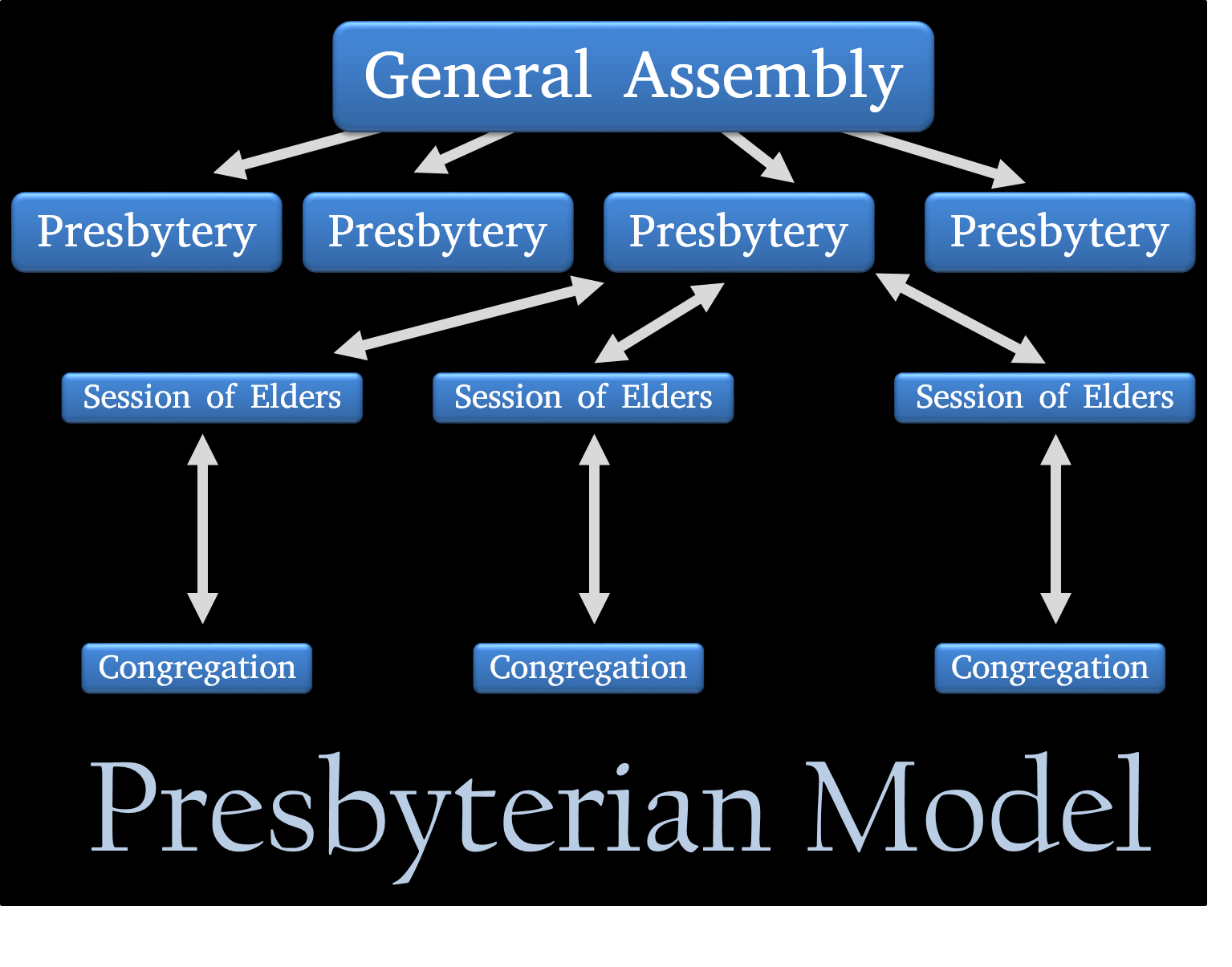

2. Presbyterian Model

What is it? This comes from the Greek presbuteros (pronounced press-BOOT-er-oss), which means “elder.” In this view, the members of the church elect elders to a “session” or board of elders. Grudem writes, “The pastor of the church will be one of the elders in the session, equal in authority to the other elders.”[3] The elders of the session run their local church, and some are also members of the presbytery, which governs over the larger church. That is, the presbytery is a group of governing elders who make decisions for all of the churches in the denomination.

Who uses it? This is used by Presbyterians, Reformed, and Lutherans.

What is their biblical basis? Advocates of this view point to Acts 6:2-6, which states,

The twelve summoned the congregation of the disciples and said, “It is not desirable for us to neglect the word of God in order to serve tables. 3Therefore, brethren, select from among you seven men of good reputation, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we may put in charge of this task. 4 But we will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.” 5 The statement found approval with the whole congregation; and they chose Stephen, a man full of faith and of the Holy Spirit, and Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicolas, a proselyte from Antioch.

From this passage, it seems that the congregation—rather than the apostles—chose these men to lead in the local church. Moreover, in 2 Corinthians 2:6, the entire local church votes on the subject of church discipline (“Sufficient for such a one is this punishment which was inflicted by the majority”).

Additionally, advocates of this view note that having an overarching church government helps support the unity in the Body of Christ, which Jesus himself taught as a virtue (Jn. 13:34-35; 17:21-23). It also helps individual churches from falling into doctrinal error or apostasy.

Strengths? This view has more accountability than the Hierarchical model. It also avoids the clergy-laity distinction. In this view, lay people are involved in significant ministry decisions. Often, lay people are involved in becoming elders, and this encourages the church to have outside thinking from people who are from the world.

Weaknesses? There are a number of weaknesses of this view:

First, sometimes local “rock stars” become elders—not the basis of ministry and character, but because of their fame or fortune in the world. Thus this model can quickly turn into a popularity contest. In a growing church, the majority are very often carnally minded, and not qualified to make important decisions like electing elders. Biblically, the majority is often wrong (e.g. the people complaining about Moses, Joshua and Caleb, etc.). Spiritual leaders should be in charge of major decisions like this.

Second, while the apostles ruled over extra-local churches in the first century, the NT never has an example of elders ruling over other churches—only their own church. Even at the Council of Jerusalem, the “whole church” played a role in the decision—even the apostolic era (Acts 15:22).

Third, unity doesn’t come from organizations, but from individuals relating to each other. Jesus was referring to relational unity—not organization unity in his high priestly prayer.

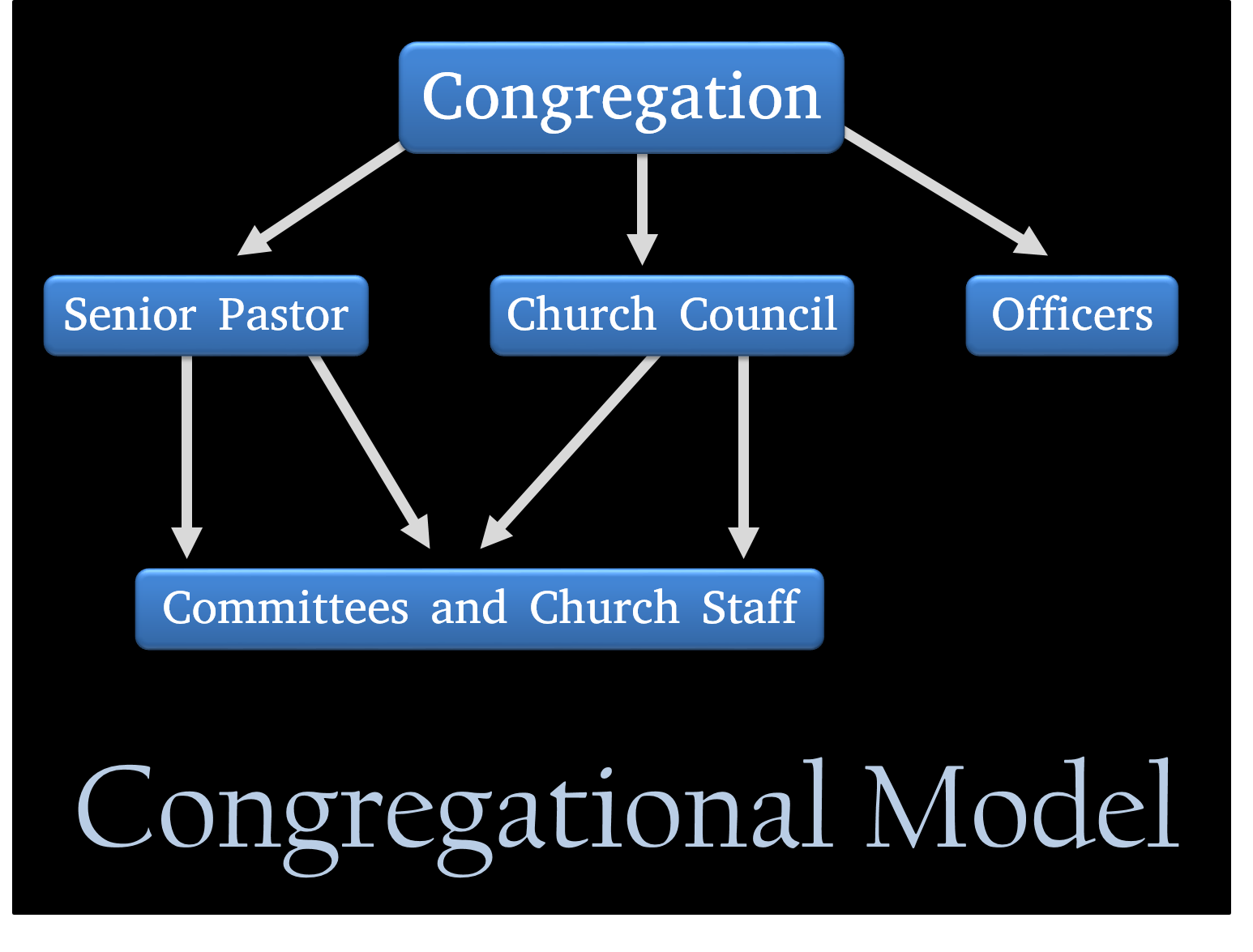

3. Congregational Model

What is it? Under this view, each individual church has its own government—without an extra-local church government to control it. The congregation rules the church by vote. Erickson writes, “Every member of the local congregation has a voice in its affairs. It is the individual members of the congregation who possess and exercise authority.”[4] They set up committees to prepare material for votes (like the budget—usually just a YES or NO vote). However, these delegates can be overruled by the congregation. Erickson writes, “They are not to exercise their authority independently of or contrary to the wishes of the people.”[5] They vote at an annual meeting for committee leaders, major changes, and the budget. The congregation can delegate decision-making power over to the pastor and staff on some issues, but the congregation has the final authority.

Churches can voluntarily join with other like-minded groups. However, Grudem writes, “However, the only authority these larger associations would have over the local congregation would be the authority to exclude an individual church from the association, not the authority to govern its individual affairs.”[6]

Who uses it? Baptists, Free churches, Churches of Christ, and independent Bible churches use this model.

What is their biblical basis? The same verses used in the Presbyterian model (to support congregational authority) also apply here (e.g. Acts 6; 2 Cor. 2:6). Additionally, Paul writes that the Body of Christ does not depend on one person, but many. He writes, “But now there are many members, but one body” (1 Cor. 12:20). Jesus implored the Pharisees, “Do not be called Rabbi; for One is your Teacher, and you are all brothers” (Mt. 23:8). He also said that believers should not “lord it over” others in authoritative positions (Mk. 10:42-45). Regarding church discipline, both Jesus and Paul appealed to the entire congregation—not just the elders—regarding such important decisions (Mt. 18:15-17; 1 Cor. 5).

Strengths? Most of us value the idea of democracy, and this seems like a good method for the church, as well. The leadership of the church should be accountable to the congregation. People under the authoritarian models often react against church government with this model.

Weaknesses? The Bible teaches legitimate authority in leadership. Paul appointed elders (Acts 14:23), and he instructed Titus to do the same (Titus 1:5). Like the Presbyterian model, this gives equal power to carnal Christians. If the pastor angers the people, then they can kick him out easily. The pastor of a church should feel free to lead without being usurped. Moreover, while the church should judge on cases of church discipline (Mt. 18:15-17; 2 Cor. 2:6), this is because individuals are close to the people in question, and probably have a better understanding of the person’s situation. However, there is no precedent for a congregation voting on major decisions in the NT church. The leaders are there to lead.

Conclusion

Which system should be adopted? We feel that the Congregational model is preferable, but it needs to be seriously modified:

First, churches should govern themselves. There is no such thing as apostolic succession of authority. While the apostles had a unique authority to govern the universal church, this authority doesn’t exist today. While individual fellowships can and should work with one another, they shouldn’t rule over one another.

Second, elders and deacons should elect elders. We don’t believe that the congregation in a growing church is qualified to vote on elders. However, the elders and deacons are qualified, because they have been proven through character and ministry (1 Tim. 3; Titus 1). This avoids a potentially carnal congregation from electing carnal elders.

Third, congregations should generally trust elders to lead the church. A leaderless group is destined to fail. Of course, elders are not sinless and can be removed from leadership (1 Tim. 5:20), but they should be generally trusted (1 Tim. 5:18-19), because of their character and history of ministry (1 Tim. 3; Titus 1).

Fourth, elders should not lead alone. Plurality in eldership helps to avoid tyranny or apostasy in the church, keeping accountability for the elders’ decisions. Paul appointed plural elders for each singular church (Acts 14:23; Titus 1:5). Likewise, Peter commanded, “Shepherd the flock [singular] of God among you [plural]” (1 Pet. 5:2).

Further Reading

Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan Publishing House. 1994. Chapter 47: “Church Government”

Erickson, Millard. Christian theology. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. 1998. Chapter 52: “The Government of the Church.”

[1] Erickson, Millard. Christian theology. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. 1998. 1081.

[2] Edward Arthur Litton, Introduction to Dogmatic Theology, ed. by Philip E . Hughes (London: James Clarke, 1960; first published in 2 vols., 1882, 1892), p. 401. Cited in Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan Publishing House. 1994. 924.

[3] Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan Publishing House. 1994. 926.

[4] Erickson, Millard. Christian theology. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. 1998. 1089.

[5] Erickson, Millard. Christian theology. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. 1998. 1091.

[6] Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI. Zondervan Publishing House. 1994. 935.