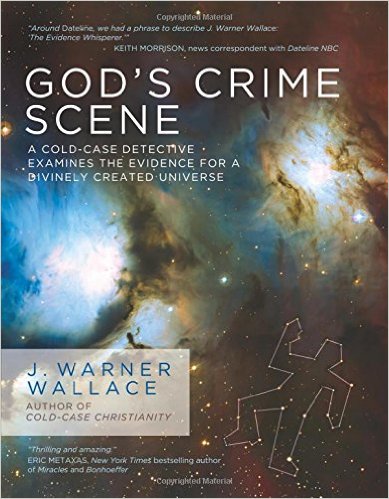

Wallace, J. Warner. God’s Crime Scene: A Cold-Case Detective Examines the Evidence for a Divinely Created Universe (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook) 2015.

I must join many others in endorsing J. Warner Wallace’s recent book God’s Crime Scene (2015). Wallace covers a number of different topics regarding the evidence for theism, divvying up each topic into eight chapters: (1) the cosmological evidence, (2) fine-tuning, (3) origin of life, (4) irreducible complexity, (5) consciousness, (6) free will, (7) morality, and (8) evil.

I must join many others in endorsing J. Warner Wallace’s recent book God’s Crime Scene (2015). Wallace covers a number of different topics regarding the evidence for theism, divvying up each topic into eight chapters: (1) the cosmological evidence, (2) fine-tuning, (3) origin of life, (4) irreducible complexity, (5) consciousness, (6) free will, (7) morality, and (8) evil.

While much has been written on the rational basis for Christian theism, three unique contributions make Wallace’s book stand out: (1) his credentials as cop, (2) his clear communication, and (3) his creative comparisons.

(1) Credentials as a cop

Warner Wallace (not to be confused with Jim Wallace of Sojourners) served as a cold-case homicide detective for two decades. Cold-case detectives have one of the toughest jobs on Earth. When a crime scene goes “cold,” this means that the detectives have given up the case due to insufficient leads. This is when “cold-case detectives” enter the scene—sometimes decades after the crime occurred.

Warner Wallace (not to be confused with Jim Wallace of Sojourners) served as a cold-case homicide detective for two decades. Cold-case detectives have one of the toughest jobs on Earth. When a crime scene goes “cold,” this means that the detectives have given up the case due to insufficient leads. This is when “cold-case detectives” enter the scene—sometimes decades after the crime occurred.

As a cold-case detective, Wallace had a perfect conviction record. That is, every one of his cases that went to trial resulted in a conviction of guilt. In one particular case which was over three decades old, Robert Shapiro (O.J. Simpson’s notorious attorney) represented the defendant. Yet Wallace’s meticulous presentation of the evidence resulted in finding the suspect guilty.

As a credentialed detective, Wallace appeared on Dateline over the years to explain several of his cases. Though Keith Morrison of Dateline doesn’t agree with Jim’s Christian beliefs, he still endorsed his book by writing,

Around Dateline, we had a phrase to describe J Warner Wallace: ‘The Evidence Whisperer.’ He would come up with some unlikely bit of long neglected flotsam, realize it was key evidence, and work it until he’d wrung out every possible lead. Jim helped bring cases to court, and our stories to life. And when I discovered he enjoys debating religious questions with an inquisitive guy like me? Well that was true joy. Mind you, we agree about almost nothing. But in this book he makes his case as always with verve and charm… just like my friend Jim.” Keith Morrison. News Correspondent, Dateline (NBC)

Experts in the field of philosophy, science, and apologetics have also come forward to endorse the book, including Lee Strobel, Stephen Meyer, Hank Hanegraaff, Paul Copan, Craig Hazen, Sean McDowell, and Michael Behe. With such a list of endorsements, Wallace finds himself in good company to make his case.

(2) Clear communication

I n his own words, Wallace described himself as an “angry atheist,” who would debate with his Christian friends regarding faith in God. It wasn’t until he investigated the evidence for himself that he discovered the credibility of the Christian worldview. After meeting Christ in 1996, Wallace served as a youth pastor, and later planted a church in 2006. During this time, he developed a robust apologetics website and podcast.

n his own words, Wallace described himself as an “angry atheist,” who would debate with his Christian friends regarding faith in God. It wasn’t until he investigated the evidence for himself that he discovered the credibility of the Christian worldview. After meeting Christ in 1996, Wallace served as a youth pastor, and later planted a church in 2006. During this time, he developed a robust apologetics website and podcast.

I suspect that his background as a skeptic and his work as a practitioner helped him to develop into such a fine communicator. While many scholars can effectively communicate to one another in the world of academia, few are able to communicate with the “person on the street.” It is here that Wallace particularly excels. In God’s Crime Scene, Wallace doesn’t dilute the academic content, so much as he carefully crafts his arguments, illustrations, and research to be accessible to his readers.

In addition to the clarity of his writing, Wallace illustrates his own pictures, which fill the pages of his book. As a grad student in Design and Architecture from UCLA, his illustrations function as excellent visual aids in explaining such complex information.

(3) Creative comparisons

Wallace offers us a creative comparison between the evidence for God and the evidence in a courtroom, giving the reader a key analogy for surveying the evidence for theism. While we may not be experts, we sit on the jury as Wallace helps us to investigate the evidence from physics, biology, consciousness, and morality.

In his introduction (pp.19-26), Wallace invites his readers to join him on a number of different cold-cases on which he himself worked. At the crime scene, Wallace notes that really only four different causes can account for the victim’s death: (1) an accident, (2) a natural cause, (3) a suicide, or (4) an intruder. When a detective arrives at the scene of a crime, he needs to discern which explanation best explains the forensic data. If the evidence can’t be explained by options 1-3, then the detective rightly concludes that an intruder committed a crime.

This illustration (the central thesis of the book to which Wallace habitually returns throughout) serves as a creative way to explain how to conduct our investigation for God. If the evidence “inside the room” (i.e. the material universe) cannot adequately explain the facts of cosmology, physics, biology, morality, and consciousness, are we not rationally allowed to consider the plausibility of a Divine Intruder? Wallace utilizes this illustration in a number of key ways:

(1) Assessing a reasonable standard of proof. When jurors render a verdict, they do so on the basis good evidence—not certainty. Of course, no one is 100% certain in any court case. Wallace writes, “The standard of proof (SOP) in the most critical of criminal trials is ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’ not ‘beyond a possible doubt.’ I’ve never conducted the perfect investigation, and we’ve never presented the perfect case before a jury… Jurors can’t wait for what might be discovered ten years from now. If there’s enough evidence to make a decision, they’re asked to make a decision.” (p.202)

(2) Determining the best explanation. When Police find a man with 54 stab wounds, they would admit that it is at least possible that 54 people each stabbed the man once. But which explanation is most plausible? 54 killers who stabbed him once, or one killer who stabbed him 54 times? Likewise, as we consider multiple lines of scientific evidence, we discover that the various explanations contradict one another or stretch our credulity when paired together. The explanation with the most explanatory power is theism, which Wallace draws together in his final chapter (“Closing Argument”).

(3) Interpreting the facts. While juror’s need nothing less than good evidence and facts in a court of law, they need something more—a careful analysis and interpretation of the evidence. Likewise, in our search for God, we need more than just a compilation of evidence. We need to think critically and draw inferences about the evidence set before us. Wallace uses his expertise to help us carefully discern the best explanation for the eight phenomena he addresses.

Wallace doesn’t just tell us what to think about the evidence for God’s existence, he teaches us how to think about it. He carefully compares principles of abductive reasoning in the field of forensics to determine the best explanation for several phenomena in nature, tactfully weighing the evidence throughout his book.

(4) Understanding the nature of a cumulative case. In a court of law, the prosecution will marshal several lines of circumstantial evidence: expert witnesses, fingerprints, footprints, DNA evidence, motive etc. Jurors listen to this evidence and then determine the best explanation. Likewise, in making his case, Wallace offers eight lines of evidence for belief in God. While some lines of evidence are stronger than others, the combined force of the evidence allows us to render a rational verdict.

(5) Explaining the urgency of rendering a verdict. If a death occurred due to an accident, a natural cause, or a suicide, we wouldn’t feel too much urgency in forensic investigation. But murder? If we suspected an intruder was responsible, urgency would infuse our search. Wallace, writes, “Murder investigations go cold when the first detectives fail to act with a sense of urgency. If they wait too long, potential witnesses are harder to locate and evidence is destroyed before it can be recovered. Even as a cold-case detective, I have a similar sense of urgency in my secondary investigation. If I wait too long, my witnesses or suspects may die of old age before I can contact and interview them. To be successful, I have to work within the lifetime of the people involved in my case.” (p.204) In the same way, we don’t have an eternity to make a decision for Christ. God expects us to pursue the truth before we leave this world to be with Christ (or he enters our world to be with us). It only makes sense to investigate the case for God’s existence, which is the greatest investigation of them all.

(6) Understanding the nature of the Divine Intruder. Lest we be turned off to comparing God to a murder suspect, Wallace shows where the analogy breaks down. In a stirring conclusion to the book, Wallace turns the tables on the reader, noting that God isn’t the criminal in this illustration; in fact, we are! He writes,

“One way to overcome your discomfort with the idea of a Divine Intruder is to rethink the nature of your home and the identity of the Intruder. I bet you never think of yourself as an intruder when you come home after a day at work or an afternoon of running errands. At your house, you are the inhabitant, not the intruder. You can’t be an intruder in your own home. The Divine Intruder we’ve described as the source for all the cosmological, biological, mental, and moral evidence in the universe is the Creator of our home. It’s His house and He’s still the primary owner and inhabitant. In our limited, self-focused view of reality, we’ve imagined this to be our universe, when in fact, it is His. We are His guests. We are the ones living in the universe God created, resisting the existence of our Creator (and landlord), and viewing Him as the intruder in our lives.” (p.201)

Conclusion

Years ago, Lee Strobel employed his skills as an investigative reporter to bring the evidence for Christianity into the public arena. Today, J. Warner Wallace has taken this investigation to the next level, using his expertise as a detective to solve the greatest case of them all: God’s existence. Wherever you land on your verdict for God, I hope you’ll agree that the expertise and the reliability of this detective is a “case closed.”