Download a free teaching series from James HERE!

What’s so special about the book of Acts? Put simply, without the book of Acts, large portions of the NT would be quite incomprehensible. This book is the linchpin that holds the NT together in a number of ways.

What’s so special about the book of Acts? Put simply, without the book of Acts, large portions of the NT would be quite incomprehensible. This book is the linchpin that holds the NT together in a number of ways.

First, Acts explains how Jesus’ message began to reach all nations—not just the nation of Israel. Before Acts, we see that Jesus focused his attention on the nation of Israel (Mt. 10:6; 15:24). Christianity was largely a Jewish religion for Jewish people. But the book of Acts demonstrates that Jesus wanted to reach all people (Acts 1:8). This is the fulfillment of the Great Commission (Mt. 28:18-20; Acts 1:8).

Second, Acts authenticates and explains the apostleship of Paul. Luke records Paul’s testimony three times (Acts 9:1-9; 22:3-21; 26:2-23). This must show that Luke “desired to establish Paul’s credentials as the apostle to the Gentiles,”[1] and this explains the authority and integrity of the thirteen letters ascribed to Paul in the NT. Indeed, without Acts, we would wonder who Paul even was!

Third, Acts explains the churches mentioned throughout the rest of the NT. In the rest of the NT, we have letters to many different Greco-Roman cities (e.g. Corinth, Thessalonica, Galatia, etc.). Without Acts, we would wonder how the gospel spread to these predominantly Gentile regions.

Fourth, Acts gives a credible case for why Christianity should be considered a legal religion in Rome. The Jewish faith was considered a legal religion by the Roman Empire, but what about Christianity? Should Rome consider Christianity to be a legal religion (under the protective umbrella of Judaism), or should it be considered a separate religion altogether? Luke seeks to demonstrate that Christianity is not a separate religion from Judaism, but rather, the fulfillment of Judaism. This could be why this letter is addressed to Theophilus, who could possibly be a Roman magistrate. We agree with earlier commentators who held that Acts was something of a “trial document” that was written for “a Roman magistrate named Theophilus and perhaps meant eventually for the eyes of the emperor.”[2]

Repeatedly, Acts records how Christianity is good for the Roman Empire, and it is being unfairly represented. The city officers apologize for imprisoning Paul and Silas (Acts 16:38-39), Gallio—the Roman official—sides with Paul and allows Christian preaching in Corinth (Acts 18:12-17), and King Agrippa II and Festus both agree that Paul had done nothing wrong (Acts 26:31-32). All of this supports the fact that the Roman Empire should be favorable to Christianity.

Fifth, Acts emphasizes the importance of prayer. Luke records examples of prayer in 20 out of the 28 chapters in this book. In total, he mentions prayer 31 times. This is quite an emphasis. Prayer was the engine that propelled the early church forward.

Sixth, Acts emphasizes the power and leadership of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit came to lead the early church just as Jesus had promised (Jn. 14:16-17, 26). In Acts, we come to understand why Jesus said it would be to their “advantage” that the Holy Spirit would come to lead them (Jn. 16:7). It is for this reason that many commentators call this book, “The Acts of the Holy Spirit,” rather than the “Acts of the Apostles.” John Polhill aptly comments, “That the mission of the church is under the direct control of God is perhaps the strongest single theme in the theology of Acts.”[3]

Seventh, Acts is a large portion of our Bible. Put together, Luke and Acts comprise 27% of the NT.[4] If we don’t know these two books well, then we are gutting over a quarter of our NT.

Table of Contents

The Historical Reliability of Acts. 5

How to use this commentary well 8

Acts 3 (Healing the Disabled man). 33

Acts 4 (Persecution from the Religious authorities). 39

Acts 5 (Ananias and Sapphira). 47

Acts 6 (Stephen’s Character). 57

Acts 7 (Stephen’s defense). 63

Acts 8 (Philip’s Ministry in Samaria). 74

Acts 9 (Paul comes to Christ). 82

Acts 10 (Cornelius and Peter). 93

Acts 11 (Recap of the Cornelius Phenomenon). 101

Acts 12 (Herod, James, and Peter). 107

Acts 13 (First Missionary Tour: Part 1). 114

Acts 14 (First Missionary Tour: Part 2). 123

Acts 15 (The Council of Jerusalem). 131

Acts 16 (Second Missionary Tour: Philippi). 139

Acts 17 (Second Missionary Tour: Thessalonica). 149

Acts 18 (Second Missionary Tour: Corinth). 160

Acts 20 (Farewell to Ephesus). 177

Acts 21 (Paul Goes to Jerusalem). 185

Acts 23 (Before the Sanhedrin). 197

Acts 25 (Governor Festus). 207

Acts 28 (Paul in house-arrest in Rome). 224

What Happened after Acts 28?. 228

Authorship

The same author wrote both Luke and Acts. Just compare the opening lines of both books:

Comparison of Luke-Acts |

|

Luke |

Acts |

|

1 Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile an account of the things accomplished among us, 2 just as they were handed down to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, 3 it seemed fitting for me as well, having investigated everything carefully from the beginning, to write it out for you in consecutive order, most excellent Theophilus; 4 so that you may know the exact truth about the things you have been taught. |

1 The first account I composed, Theophilus, about all that Jesus began to do and teach, 2 until the day when He was taken up to heaven, after He had by the Holy Spirit given orders to the apostles whom He had chosen. 3 To these He also presented Himself alive after His suffering, by many convincing proofs, appearing to them over a period of forty days and speaking of the things concerning the kingdom of God. |

Because of the similarities between Luke and Acts, virtually all scholars believe that whoever wrote Luke, also wrote Acts.[5] Indeed, this is the overwhelming consensus of NT scholarship today:

- Hemer states that it is “widely agreed that the Third Gospel and Acts share common authorship.”[6]

- Longenecker writes that “hardly anyone today would dispute this basic observation.”[7]

- Marshall writes that “the vast majority of scholars [assume] common authorship of the Gospel and Acts.”[8]

- Polhill writes, “Scholars of all persuasions are in agreement that the third Gospel and the Book of Acts are by the same author.”[9]

Luke is the best candidate for the authorship of these two books. For a long defense of Luke’s authorship see our earlier article, “Who Wrote the Four Gospels?” Both the external and internal evidence support that Luke was the author of these two books. In fact, Luke’s “authorship was unquestioned until 18th century skepticism.”[10]

Luke was a physician (Col. 4:14), and most likely a Gentile convert. Not only does he have a Gentile name, but he is also listed alongside other Gentiles. Luke was the only one with Paul at the end of his life (2 Tim. 4:11), and Paul mentions Luke to Philemon (Phile. 24). Beyond these passages, we don’t know much more about this person, and we would “perhaps do better simply to admit that we do not know very much about Luke’s background.”[11]

Date

The majority of scholars “date Acts somewhere between AD 80 and 95.”[12] Polhill[13] dates Acts sometime between AD 70 to AD 80. Marshall[14] dates the book sometime just before AD 70. However, we think that several strong lines of evidence date the book quite early—around AD 62. For a defense of this early date of Acts, see our earlier article, “Evidence for an Early Dating of the Four Gospels.”

The Historical Reliability of Acts

Sir William Ramsay (1851-1939) lectured in classical art and archaeology at Oxford University. When he began an archaeological research project in Asia Minor, he needed to create his own maps of this massive area. He consulted the book of Acts, but he considered it a second century book without much historical value. But after his long and extensive archaeological study, Ramsay found that Acts turned out to be reliable time and time again. He writes,

I began with a mind unfavorable to [Acts], for the ingenuity and apparent completeness of the Tübingen theory[15] had at one time quite convinced me. It did not lie then in my line of life to investigate the subject minutely; but more recently I found myself often brought into contact with the book of Acts as an authority for the topography, antiquities, and society of Asia Minor. It was gradually borne in upon me that in various details the narrative showed marvelous truth. In fact, beginning with the fixed idea that the work was essentially a second century composition, and never relying on its evidence as trustworthy for first century conditions, I gradually came to find it a useful ally in some obscure and difficult investigations.[16]

Ramsay’s skepticism of Acts began to weaken when he read that Paul “fled [from Iconium] to the cities of Lycaonia, Lystra and Derbe” (Acts 14:6). Ramsay originally thought that this was an error, because Iconium was in Lycaonia at the time. According to Ramsay, this would be as bad as saying that someone fled from London to England.[17] Yet, he went on to discover that Iconium was not in the district of Lycaonia in the first-century. Instead, it was outside of these geographical boundaries at that time. This got Ramsay’s attention.

Eventually, after 30 years of research, Ramsay ended up becoming a follower of Christ. Later in life, he wrote, “Luke’s historicity is unsurpassed in respect to its trustworthiness… Luke is a historian of the first rank; not merely are his statements of fact trustworthy… this author should be placed along with the very greatest of historians.”[18]

Colin J. Hemer was originally an expert and lecturer in the Classics, but he turned his attention to NT scholarship studying under the distinguished NT scholar F.F. Bruce. Hemer became a full-time research scholar at Tyndale House and a lecturer at the University of Manchester. In his book The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (1987), Hemer documents roughly 180 “undesigned coincidences”[19] that align with secular history, culture, geography, etc. To take a small sample, Luke knew:

- Annas still had prestige in Jerusalem, even after Caiaphas took over for him (c.f. Luke 3:2; Acts 4:6).

- details about the military guard (Acts 12:4).

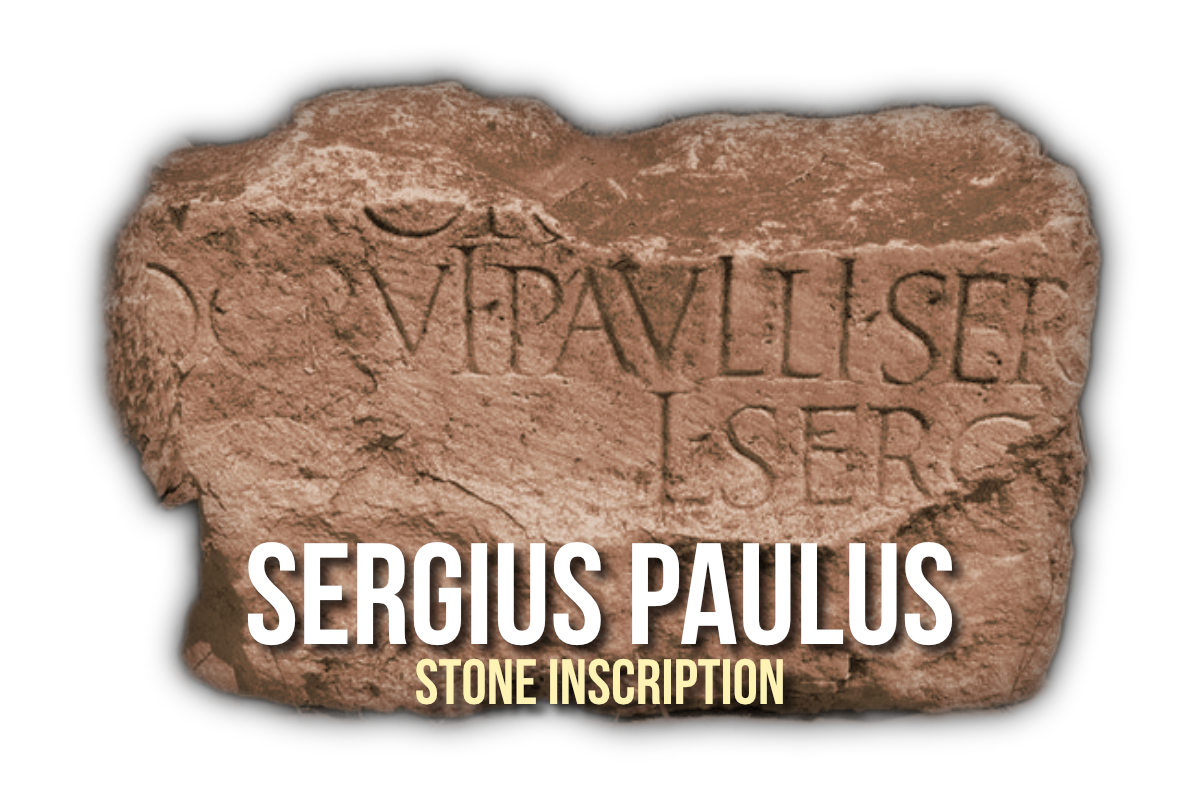

- the name of the correct proconsul at Paphos (Acts 13:7).

- the resting places for a voyage from Philippi to Thessalonica (Acts 17:1; Amphipolis and Apollonia).

- geography and navigational details about the voyage to Rome (Acts 27-28).

- river-ports (Acts 13:13), coasting ports (Acts 14:25), and sea ports (Acts 16:11-12) for Paul’s travels (c.f. Acts 21:1; 27:6; 28:13).

- Iconium was considered a city in Phrygia, rather than Lycaonia (Acts 14:6).

- the native language spoken in Lystra—unusual in a major cosmopolitan city (Acts 14:11).

- the common worship in Lystra (Acts 14:12).

- the river Gangites flowed close to the walls of Philippi (Acts 16:13).

- Thyatira was a center of fabric dyeing, which has been confirmed by a number of inscriptions (Acts 16:14).

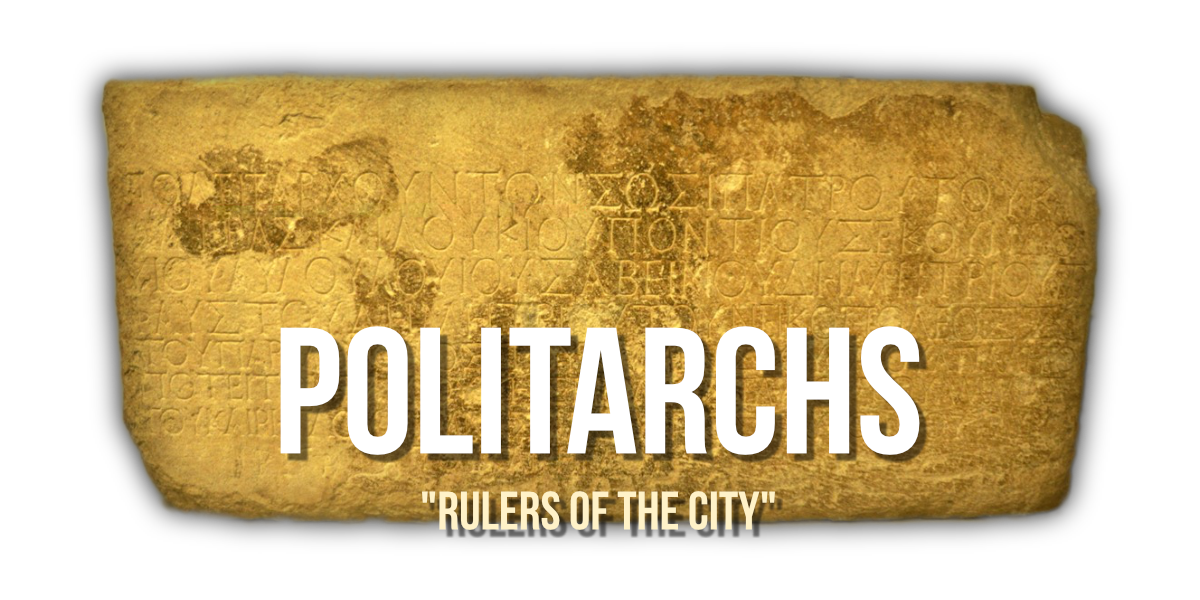

- the magistrates were called “politarchs” (Acts 17:6).

- there was an agora in Athens, where philosophical debate was popular (Acts 17:17).

- it was common Athenian slang to call someone a “babbler” (Acts 17:18).

- the altars to “unknown gods”—also mentioned by Pausanias and Diogenes Laertius (Acts 17:23).

- Epimenides, showing that Paul was familiar with current Athenian religion. Epimenides was a part of Diogenes’ story about “unknown gods” (Acts 17:28).

- Athenians were hostile to the concept of resurrection (Acts 17:32).

- Claudius’ expulsion of the Jews from Rome, placing it in the proper time frame (Acts 18:2).

- the name of the proconsul of Corinth (Acts 18:12).

- the local philosopher in Ephesus named Tyrranus (Acts 19:9).

- the goddess Artemis, who shrines have been uncovered in Ephesus (Acts 19:24).

- the expression “The great goddess Artemis.” This was a phrase in Ephesus at the time that he was writing (Acts 19:27).

- the historic Ephesian theatre (Acts 19:29).

- the correct title for the chief magistrate in Ephesus (Acts 19:35).

- there were two “proconsuls” in Ephesus—instead of one (Acts 19:38).

- typical ethnic names at the time (Acts 20:4-5).

- the exact sequence of places in their travel (Acts 20:14-15).

- eyewitness comments in portions of the voyage (Acts 21:3).

- the high priest Ananias, and he placed him in the correct time period (Acts 23:2).

- the governor Felix, and he placed him in the correct time period (Acts 23:24).

- common Roman court procedure (Acts 24:5; 19; 25:18).

- the successor of Felix, Porcius Festus (Acts 24:27).

- king Agrippa II, whose kingdom had been recently been extended (in 56 C.E.). Luke placed his visit in the exact timeframe (Acts 25:13).

- a poorly sheltered roadstead on the way to Rome (Acts 27:8).

- intricate details of ancient sailing, particularly in this region (Acts 27).

- the names of the stopping places along the Appian Way on the way to Rome (Acts 28:15).

- Pilate was procurator (26-36 C.E.).

- Herod Antipas was tetrarch of Galilee (4 B.C.E.-39 C.E.).

- Philip, his brother, was tetrarch of Ituraea and Trachonitis (4 B.C.E.-34 C.E.).

Roman historian A.N. Sherwin-White also strongly affirmed the historical reliability of Acts. At the end of his Sarum Lectures, he wrote, “For Acts the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming… Any attempt to reject its basic historicity even in matters of detail must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted.”[20] Indeed, many notable classicists and historians affirm the historicity of Acts:[21]

- F.F. Bruce was a lecturer of classics before turning to NT scholarship.

- M. Blaiklock was a classics professor in New Zealand.

- N. Sherwin-White was a historian of Greco-Roman history at Oxford University.

- Colin J. Hemer was a classicist who turned to NT scholarship at Tyndale House and the University of Manchester.

- Irina Levinskaya was a Russian historian.

We will explore the historical confirmation of these details in greater detail in our commentary below.

How to use this commentary well

For personal use. We wrote this material to build up people in their knowledge of the Bible. As the reader, we hope you enjoy reading through the commentary to grow in your interpretation of the text, understand the historical backdrop, gain insight into the original languages, and reflect on our comments to challenge your thinking. As a result, we hope this will give you a deeper love for the word of God.

Teaching preparation. We read through several commentaries in order to study this book, and condensed their scholarship into an easy to read format. We hope that this will help those giving public Bible teachings to have a deep grasp of the book as they prepare to teach. As one person has said, “All good public speaking is based on good private thinking.”[22] We couldn’t agree more. Nothing can replace sound study before you get up to teach, and we hope this will help you in that goal. And before you complain about our work, don’t forget that the price is right: FREE!

Discussion questions. Each section or chapter is outfitted with numerous discussion questions or questions for reflection. We think these questions would work best in a small men’s or women’s group—or for personal reading. In general, these questions are designed to prompt participants to explore the text or to stimulate application.

Discussing Bible difficulties. We highlight Bible difficulties with hyperlinks to articles on those subjects. All of these questions could make for dynamic discussion in a small group setting. As a Bible teacher, you could raise the difficulty, allow the small group to wrestle with it, and then give your own perspective.

As a teacher, you might give some key cross references, insights from the Greek, or other relevant tools to help aid the study. This gives students the tools that they need to answer the difficulty. Then, you could ask, “How do these points help answer the difficulty?”

Reading Bible difficulties. Some Bible difficulties are highly complex. For the sake of time, it might simply be better to read the article and ask, “What do you think of this explanation? What are the most persuasive points? Do you have a better explanation than the one being offered?”

Think critically. We would encourage Bible teachers to not allow people to simply read this commentary without exercising discernment and testing the commentary with sound hermeneutics (i.e. interpretation). God gave the church “teachers… to equip God’s people to do his work and build up the church, the body of Christ” (Eph. 4:11-12). We would do well to learn from them. Yet, we also need to read their books with critical thinking, and judge what we’re reading (1 Cor. 14:29; 1 Thess. 5:21). This, of course, applies to our written commentary as well as any others!

In my small men’s Bible study, I am frequently challenged, corrected, and sharpened in my ability to interpret the word of God. I frequently benefit from even the youngest Christians in the room. I write this with complete honesty—not pseudo-humility. We all have a role in challenging each other as we learn God’s word together. We would do well to learn from Bible teachers, and Bible teachers would do well to learn from their students!

At the same time, we shouldn’t disagree simply for the sake of being disagreeable. This leads to rabbit trails that can actually frustrate discussion. For this reason, we should follow the motto, “The best idea wins.” If people come to different conclusions on unimportant issues, it’s often best to simply acknowledge each other’s different perspectives and simply move on.

Review of Commentaries

Darrell L. Bock, Acts, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007).

This is an excellent technical commentary on the book of Acts. It seems that Bock leaves no questions unanswered, and he offers encyclopedic information about the historical background of Acts. This is a must-read commentary for the serious student of the book of Acts. Very well done!

Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990).

This is not a commentary on Acts. Rather, it is the best historical defense of the Book of Acts in print. Sadly, Hemer died in 1987 before he could finish the final three chapters of his book. We only wonder what Hemer would’ve done for NT scholarship if he had lived longer.

Ajith Fernando, Acts: NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998).

Fernando is not only a scholar but also a practitioner. These rare qualities shine through his commentary. His sections entitled “Bridging Context” were deeply insightful, and worth the price of the commentary. This is by far the best pastoral commentary on Acts.

F.F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1988).

Bruce was a classicist who turned his considerable talents toward NT scholarship. Even though this commentary is getting old, it is still filled with sound scholarship on Acts. At the same time, we find Bruce’s historical scholarship to be far better than his theological commentary.

John B. Polhill, Acts, vol. 26, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1992).

Polhill offers enough details and historical background to make it a good commentary without getting too bogged down in the details. We also appreciated his interpretive insights. Overall, this was a quite good commentary.

Richard N. Longenecker, “The Acts of the Apostles,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: John and Acts, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 9 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1981).

We read the older (1981) version of Longenecker’s commentary. It was quite good, but we would suggest reading the updated version (2005) which is updated with more modern research. The new version is found in the Revised Expositor’s Bible Commentary.

I. Howard Marshall, Acts: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 5, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1980).

In his earlier book Luke: Historian and Theologian (1970), Marshall was one of the better scholars to defend the historicity of Acts against the works of Dibelius, Conzelmann, and Haenchen. In this commentary, Marshall regularly interacts with critical scholarship, defending the historicity of Acts. Marshall’s commentary is short and to the point. However, he lacks both insightful pastoral insight and technical rigor. If you are looking for a pastoral commentary, read Fernando. And if you are looking for a technical commentary, read Bock or Bruce.

Commentary on Acts

Unless otherwise stated, all citations are taken from the New American Standard Bible (NASB).

Acts 1 (Jesus’ Ascension)

Introduction

(1:1) The first account I composed, Theophilus, about all that Jesus began to do and teach.

What is the “first account”? The opening verses closely parallel the gospel according to Luke (Lk. 1:1-4). So, this book is the sequel to Luke’s biography about Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. Christ “began” his ministry in his life on Earth, and it hasn’t ended yet. The book of Acts will go on to show the great works that the Holy Spirit will continue to do through his followers.

Who was Theophilus?

Theophilus was a real person—not a symbolic name. The name “Theophilus” is a compound word that means friend (philys) of God (theos).[23] Origen (AD 250) held that Theophilus a symbolic name for a person who was a friend of God—not a specific individual.[24] This shouldn’t surprise us because Origen looked for allegorical interpretations in most biblical texts. Yet, few have followed in his footsteps. Bock,[25] Bruce,[26] Liefeld,[27] Morris,[28] Stein,[29] Green,[30] and Marshall[31] hold that this refers to a literal person for a number of reasons. For one, it was common for an author to address his book to a specific individual. Josephus introduced his books (e.g. Antiquities, Autobiography, Against Apion) by writing to “Epaphroditus, most excellent of men” (Against Apion 1.1), and he introduced his second volume by writing, “By means of the former volume, my most honored Epaphroditus, I have demonstrated our antiquity” (Against Apion 2.1).[32] Second, Theophilus was a common name at the time. Third, the designation “most excellent” fits with an actual official—not a symbolic person. Fourth, if Luke dedicated his book to a symbolic person, this would “be unparalleled in Luke’s literary culture.”[33] Indeed, Theophilus was most likely Luke’s “patron,” who “met the costs of publishing the book.”[34] We agree with older commentators who argue that one of Luke’s purposes was to show that Christianity wasn’t dangerous to the Roman Empire. This was one of the reasons why Luke wrote for Theophilus.

Theophilus held a high social status. Luke uses the word “most excellent” (kratistos) elsewhere to refer to Roman governors (Acts 23:26 “most excellent governor Felix”; 24:3 “most excellent Felix”; 26:25 “most excellent Festus”). This is why it’s quite likely that Theophilus held a high status of some kind in the Roman world.

Theophilus was most likely a believer in Jesus. Earlier, Luke wrote to Theophilus, “[I wrote my gospel] so that you may know the exact truth about the things you have been taught” (Lk. 1:4). This implies that Theophilus was already acquainted with Christian teaching.

(1:2) Until the day when He was taken up to heaven, after He had by the Holy Spirit given orders to the apostles whom He had chosen.

Christ’s work continued “until the day he was taken up,” and it also continued beyond “by his Spirit in his followers.”[35] At this point, Christ was replaced by the Holy Spirit, just as he promised: “I will ask the Father, and He will give you another Helper, that He may be with you forever” (Jn. 14:16).

(1:3) To these He also presented Himself alive after His suffering, by many convincing proofs, appearing to them over a period of forty days and speaking of the things concerning the kingdom of God.

What were these convincing proofs? Surely, this is referring to Jesus’ resurrection appearances, his miracles, and his demonstration of his fulfillment of OT prophecy. During this time, Jesus led a Bible study explaining his fulfillment of OT prophecy (Lk. 24:25-27, 44-49). The Greek term for “convincing proofs” (tekmeriois) doesn’t refer to 100% certainty. Even Aristotle didn’t use it this way; instead, it refers to a “compelling sign” (Aristotle, Rhetorica 1, 2, 16). BDAG defines it as “that which causes something to be known in a convincing and decisive manner, proof” (cf. Josephus, Antiquities, 17.5.6 §128; 3 Macc. 3:24).[36]

(1:4-5) Gathering them together, He commanded them not to leave Jerusalem, but to wait for what the Father had promised, “Which,” He said, “you heard of from Me; 5 for John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now.”

Why did the disciples need to wait for the Holy Spirit? This was an important lesson that the disciples needed to learn before doing anything else: They needed to learn dependence on God. They weren’t ready to begin their mission until they were given the power and guidance to accomplish it. After all, Jesus commanded the disciples to do the impossible (e.g. make disciples, preach the gospel, engage in spiritual warfare, save souls, etc.), and they needed to learn to connect to supernatural power (Lk. 24:49; Jn. 7:37-38; 14-16).

“Not many days from now.” Pentecost arrives ten days after this point (Acts 2:1-4), because 40 days had already gone by (Acts 1:3; cf. 11:16).

(1:6) So when they had come together, they were asking Him, saying, “Lord, is it at this time You are restoring the kingdom to Israel?”

“Restoring the kingdom to Israel?” On face value, this question implies that national Israel will return in the future. Yet, amillennial interpreters argue that their question was completely misguided:

John Calvin: “There are as many errors in the question as words.”[37]

Ajith Fernando: “It must have saddened the heart of Jesus to hear his disciples ask about the time of restoring the kingdom to Israel (v. 6). He had taught them about the kingdom of God, but they talk about the kingdom of Israel.”[38]

John Stott: “The verb, the noun and the adverb of their sentence all betray doctrinal confusion about the kingdom. For the verb restore shows that they were expecting a political and territorial kingdom; the noun Israel that they were expecting a national kingdom; and the adverbial clause at this time that they were expecting its immediate establishment.”[39]

I. Howard Marshall: “The disciples would appear here as representatives of those of Luke’s readers who had not yet realized that Jesus had transformed the Jewish hope of the kingdom of God by purging it of its nationalistic political elements.”[40]

We respectfully disagree with these commentators. In fact, this is a compelling passage in support of Dispensational theology. The disciples believed that God was going to work through national Israel again (Rom. 11:15-16; 25-29), and Jesus didn’t correct them. In fact, he affirmed and answered their question! This would have been the perfect time for Jesus to correct their false theology, but he simply says that they won’t know the time (Mt. 24:36; Mark 13:32; 1 Thess. 5:1). Jesus makes them focus on the Church Age. For more on this subject, see my book Endless Hope or Hopeless End (2016).[41]

(1:7) He said to them, “It is not for you to know times or epochs which the Father has fixed by His own authority.”

Why can’t Jesus tell us the time of his return? We are speculating to some degree. However, one reason for keeping his return secret is so Christians in every generation would live with the expectancy of the Second Coming. Moreover, if we had a date, people would likely go insane over this. Indeed, God didn’t reveal a date, and people still go crazy over this!

(1:8) “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the remotest part of the earth.”

The disciples were only focused on Israel (v.6). So, Jesus redirects their mindset to the whole globe. This is a repeated theme throughout Acts: The disciples are repeatedly slow and shocked at how God wants to reach the Gentiles. But just as Jesus predicts, the gospel reaches Jerusalem (Acts 2), then Samaria (Acts 8), and even Rome (12:25ff).

Sometimes this “power” is seen in miracles (Acts 2:22; 3:12; 4:7; 8:13; 10:38; 19:11) and other times in courage and strength (Acts 4:33; 6:8). It’s interesting that the disciples were constantly fumbling around throughout the gospels, but after they get the Holy Spirit, they transform into powerful men of conviction and courage.

Jesus’ Ascension

(1:9) “And after He had said these things, He was lifted up while they were looking on, and a cloud received Him out of their sight.”

In the OT, clouds represented God’s presence (Ex. 16:10; Ps. 104:3).[42] Thus, this action demonstrates that Jesus was going directly to heaven. The OT includes other examples where God takes someone bodily into heaven, such as Enoch (Gen. 5:24) and Elijah (2 Kin. 2:11).

(1:10-11) And as they were gazing intently into the sky while He was going, behold, two men in white clothing stood beside them. 11 They also said, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking into the sky? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in just the same way as you have watched Him go into heaven.”

We might imagine how amazing it would be to see Jesus taken up in this way. The disciples are slack-jawed and stunned. It takes the angels to get them reoriented.

(1:12) Then they returned to Jerusalem from the mount called Olivet, which is near Jerusalem, a Sabbath day’s journey away.

“The Mount called Olivet.” Jesus left from Mount Olivet, and he will return there at his Second Coming (Zech. 14:4).

“A Sabbath day’s journey” was just under a mile away (~1,200 yards). The fact that Luke uses a Jewish expression to define the measurement implies that he collected this information from a Jewish eyewitness. For one, he only uses this measurement when writing about Jerusalem. He doesn’t use it for the rest of the book. Moreover, Luke was a Gentile, and he was most likely writing to Gentiles. It’s odd that he would use a Jewish measurement. He couldn’t have been writing to a Jewish audience, because any Jewish person would know how far Olivet is from the nation’s capital. Therefore, it seems likely that this is an undesigned coincidence that tells us that Luke is using Jewish eyewitness testimony. At the very least, it implies that Luke consulted with a Jewish source—whether an eyewitness or not.

(1:13) When they had entered the city, they went up to the upper room where they were staying; that is, Peter and John and James and Andrew, Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew, James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon the Zealot, and Judas the son of James.

Is this the same “upper room” as the Last Supper? We’re not sure. The term used here for “the upper room” (hyperōon) is different than the one used by Luke regarding the “upper room” (anagaion) used for the Last Supper (Lk. 22:11-12). Yet, Luke uses the article in Greek: This isn’t just an upper room, but the upper room. It could be the upper room of the Last Supper (Mk. 14:12ff) or the room of Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances (Lk. 24:33ff; Jn. 20:19, 26). Commentators like Marshall[43] aren’t certain about this conclusion, but Bruce[44] thinks it’s certainly possible.

What a rag tag group of men! This is a group of cowardly (Peter), violent (Simon the Zealot), skeptical (Thomas), blindly ambitious (James and John), tax-collecting (Matthew), and uneducated men (Acts 4:13). Yet these are the people Jesus chose to build his church. This list mirrors Luke’s earlier list from his gospel (Lk. 6:14-16), and it is composed of only eleven men—not twelve—because Judas was dead (Mt. 27:5; Acts 1:18). For a full description of the disciples, see our comments on Matthew 10:2-4, Mark 3:16-19, or Luke 6:14-16.

(1:14) These all with one mind were continually devoting themselves to prayer, along with the women, and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with His brothers.

They were “continually devoting themselves to prayer,” even though they knew that Jesus promised the coming of the Holy Spirit. It’s appropriate to pray—even if we know the guaranteed outcome. They were doing the same activity that they would later teach the early church (Acts 2:42).

“Along with the women.” Luke repeatedly mentions women as key followers of Jesus (Lk. 8:2; 23:49; 23:55-24:10). Yet, this is also the final mention of Mary (Jesus’ mother) in the Bible.

“One mind.” Was their prayer a cause or an effect of their unity? Or perhaps both?

What changed in the lives of Jesus’ brothers? Just six months before Jesus’ death, Jesus’ brothers were skeptical of him (Jn. 7:5), but here they are followers of him. What changed? Jesus’ resurrection deeply affected Jesus’ brother James (1 Cor. 15:7), and it must have had a similar effect on his other brothers.

Replacing Judas

(Acts 1:15-26) Does this passage support papal succession?

(1:15) At this time Peter stood up in the midst of the brethren (a gathering of about one hundred and twenty persons was there together).

If this upper room could fit about 120 people, the person must have been somewhat wealthy.[45]

Does the number “120” carry significance for forming a Sanhedrin? Citing the Mishnah (m. Sanhedrin 1:6), Polhill writes, “In rabbinic tradition 120 was the minimum requirement for constituting a local Sanhedrin.”[46] We reject seeing any significance in the number 120. For one, as we continue to read in the Mishnah, rabbi Nehemiah states that the number needed for a local Sanhedrin is “two hundred and thirty” (m. Sanhedrin 1:6 S). This implies that the number was hardly uniform at this time. Second, Luke says that this was “about one hundred and twenty.” If this was supposed to carry symbolic significance, we would expect a more accurate figure. Finally, what exactly is Luke trying to signify by stating that the Christians were a local Sanhedrin? Does this mean that they are the new leadership of Israel? If so, why not pick the number 70 (or 71) to match the official Sanhedrin? In our view, no symbolic meaning exists: Luke recorded that there were 120 people simply because the number of people happened to be one more than 119 and one less than 121!

(1:16) [Peter said,] “Brethren, the Scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Holy Spirit foretold by the mouth of David concerning Judas, who became a guide to those who arrested Jesus.”

It’s no wonder that Peter would start to talk about the fulfillment of Scripture. He just recently sat in a Bible study with Jesus for 40 days, seeing how the OT predictions came to fulfillment (Lk. 24:44).

(Acts 1:16, 20) Doesn’t this passage imply fatalism?

(1:17) “For he was counted among us and received his share in this ministry.”

“Share in this ministry.” Apparently, it’s possible for non-believers to do ministry.

Peter’s language is very Jewish. It is strikingly similar to the Palestinian Targum for Genesis 44:18 (“Benjamin who was numbered with us among the tribes and will receive a portion and share with us in the division of the land”). Thus, Marshall holds that “Luke is here dependent on Palestinian traditions.”[47] Again, this confirms that Luke is interviewing the eyewitnesses in the area—not inventing speeches.

(1:18-19) (Now this man acquired a field with the price of his wickedness, and falling headlong, he burst open in the middle and all his intestines gushed out. 19 And it became known to all who were living in Jerusalem; so that in their own language that field was called Hakeldama, that is, Field of Blood.)

For the difficulty of reconciling how Jesus died, see our video that addresses this, or read our earlier article on the subject below.

(Acts 1:18) How did Judas die?

(1:20) “For it is written in the book of Psalms, ‘Let his homestead be made desolate, and let no one dwell in it’; and, ‘Let another man take his office.’”

Peter cites from two OT texts to support his case: Psalm 69:25 and Psalm 109:8.

Psalm 69:25. In this psalm, enemies try to kill an incredibly righteous man, which is often applied by the apostles to the Messiah. Thus, “it would be natural to find in this Psalm a prophecy or type of the betrayer of Jesus.”[48] The original psalm refers to plural enemies (“their homestead”), while Peter applies it to a singular enemy in Judas (“his homestead”).

Psalm 109:8. In this psalm, the author curses his enemy with a number of prayers for divine judgment. Because the enemy is so wicked, it makes sense that the psalmist would write that the man should resign his office. The psalmist “prays that a certain enemy may die before his time and be replaced in his responsible position by someone else.”[49] Peter sees a similarity in Judas’ loss of the ultimate inheritance of eternal life.

Does this concept support apostolic succession? No. The apostles were a closed fraternity of men—not an ongoing succession that was meant to continue to this day. After all, when James is killed by Herod (Acts 12:1-2), the church doesn’t replace him. Moreover, Judas wasn’t even a believer in Jesus (Jn. 6:70-71; 17:12; Mt. 26:24). So, he hardly should be used as an example of apostolic succession. Furthermore, this is the only known example of replacing an apostle. Polhill writes, “James was not replaced after his martyrdom (12:2). It was necessary to replace Judas because he had abandoned his position. His betrayal, not his death, forfeited his place in the circle of Twelve.”[50] Jesus had promised that “twelve” apostles would rule over Israel (Mt. 19:28; Lk. 22:30). If the apostles were constantly replaced, we would have far more than “twelve” ruling over the nation.

(1:21-22) “Therefore it is necessary that of the men who have accompanied us all the time that the Lord Jesus went in and out among us—22 beginning with the baptism of John until the day that He was taken up from us—one of these must become a witness with us of His resurrection.”

Why did they need to bring the apostolic team back up to twelve men? This must be symbolic of the twelve tribes of Israel,[51] and there seems to be a New Testament fulfillment involved here (cf. Mt. 19:28; Lk. 22:30; Rev. 21:10; 12; 14).

“Accompanied us all the time… a witness with us of His resurrection.” Peter is saying that the next apostle needed to be with Jesus from A to Z—from the beginning of his earthly ministry (“baptism”) to the end (“taken up”). The focus is also on the fact of Jesus’ resurrection. A “witness” was not a subjective concept to them, but more like a witness in a court of law, reporting the facts.

(1:23) So they put forward two men, Joseph called Barsabbas (who was also called Justus), and Matthias.

There is some later historical tradition about these two men. Later history states that Joseph drank poison without dying (Eusebius, Church History 3.39.8; Philip of Side, Christian History), which seems quite suspicious. Moreover, Matthias was apparently one of the 70 disciples and a missionary to the Ethiopians (Lk. 10:1; Eusebius, Church History 1.12.3).[52] This could be true, but the report is so late that we’re not sure. Honestly, we don’t know much about them. In fact, this is the last time they’re mentioned in the NT. Of course, Joseph (or Justus) could be the man mentioned in Colossians 4:11.

Why did they have two names? We see this phenomenon throughout the NT. People at this time had both a “Gentile name as well as his Jewish one.”[53]

(1:24-25) And they prayed and said, “You, Lord, who know the hearts of all men, show which one of these two You have chosen 25 to occupy this ministry and apostleship from which Judas turned aside to go to his own place.”

Since the Lord Jesus was the one to elect the apostles (Acts 1:2) and he is called “Lord” (Acts 1:21), it seems that they’re praying directly to Jesus here.[54] This would support the deity of Christ.

“Judas turned aside to go to his own place.” This can be rendered, “A place of his own choosing.”[55] All who go to hell choose to go there.

(1:26) And they drew lots for them, and the lot fell to Matthias; and he was added to the eleven apostles.

Were the apostles wrong in picking Matthias? Some commentators hold that it was wrong for the apostles to pick Matthias, and they should’ve waited for God to pick the apostle Paul.[56] Yet, nothing in this text—nor any other—indicates that this was a failure on their behalf. Instead, they were filling the vacancy for the inauguration of the church.

(Acts 1:26) Should we cast lots?

How did Jesus prepare the disciples for the growth in chapter 2?

The church began with only 120 people (Acts 1:15). Yet, by the next chapter, we’ll see 3,000 added (Acts 2:41). Yet, these 120 people turned the world upside down! How did Jesus prepare these people to make such an impact?

Jesus taught the disciples the crucial lesson of dependence, rather than self-effort. The disciples had already tried the power of self-effort (Mk. 14:31), but it failed miserably and all of them abandoned Jesus in the most critical moment. Jesus’ solution was the gift of the Holy Spirit. He taught them that they couldn’t change the world without the power and guidance of the Holy Spirit. This was so crucial that Jesus told them to wait for a week and a half before they shared their faith. We should not wait to share our faith (because we already have the Holy Spirit!). But what does it look like to depend on the Holy Spirit for power and guidance in your life?

Jesus appointed Christian leaders to prepare them for the growth. In the next chapter, the 3,000 new Christians listened to the “apostles’ teachings” in order to grow (Acts 2:42). Jesus had the final say through the casting of lots (Acts 1:27). Yet, the apostles chose the two candidates through assessing their personal qualifications, asking in prayer, and accepting the divine appointment. We do not create Christian leaders, but rather, we recognize them.

Jesus told them right from the beginning what their mission was going to be. He said that they would reach the Jews, the Samaritans, and the entire world (Acts 1:8). Then, like now, the disciples were slow to understanding and remembering this vision. Yet, Jesus made this crystal clear to them.

Jesus prepared the disciples with teaching and field training before sending them out. Jesus didn’t give the disciples years of seminary training before sending them out as “ordained ministers.” But he did give them equipped and training. He served alongside them for three years, and then, it seems that he did intensive Bible study with them for 40-days (Acts 1:3). Then, he gave them his commission, gave them the Holy Spirit, and gave clear signs to go.

Jesus stayed with them. Even though Jesus ascended and left, he would be with them “always, even to the end of the age” (Mt. 28:20). He did this through his Holy Spirit, and his guidance of his church. The reason that Jesus “ascended far above all the heavens” was so that he could “fill all things” (Eph. 4:10).

Questions for Reflection

What is the significance in the fact that the apostles left this decision up to God? What application does this have for us today?

Should we still cast lots today? If not, why would we follow some of the application from this verse, but not the part about casting lots?

Acts 2 (Pentecost)

Luke anticipated this event (Lk. 3:15-17; 24:47-49; Acts 1:4-5), and the OT foreshadowed this event as well (Num. 11:29; Isa. 32:15; 44:3; Ezek. 36:27). We are about to read about an event that changed our world forever: the launching of Jesus’ church.

(Acts 2:1-4) Does this passage support the Pentecostal doctrine of the second blessing?

(2:1) When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place.

What was Pentecost? The term “Pentecost” comes from the word “pente” which means “50.” This festival was 50 days after the Passover. This feast was also referred to as the “Festival of Weeks” or the “Festival of First Fruits” (Ex. 23:16; Lev. 23:17-22; Num. 28:26-31; Deut. 16:9-12). This was one of the three great pilgrim festivals (along with Passover and Tabernacles), where Jews from all over the known world would make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to dedicate the “first fruits” of their harvest to God. They would also renew their commitment to the law of God (Jubilees 6:17; b Peshaim 68b; M Tanchuma 26c). It was a very popular festival—likely because the weather was often better during this time of year.[57] Just as Jewish people would bring a great harvest to God during Pentecost, God was bringing a great harvest of people to himself on Pentecost. For the prophetic fulfillment of Passover and Pentecost, see “Foreshadowing in the Festival System.”

Luke’s emphasis is on the when of the event—not the where. The Holy Spirit arrived in a “house” (v.2). Was it the “upper room” mentioned earlier (1:13)? Perhaps. But we simply aren’t sure. It seems that he isn’t specific about the location because the place doesn’t matter. Just like God made a burning bush holy in Exodus 3, he made this unnamed house holy when he filled these believers with the Holy Spirit.

(2:2) And suddenly there came from heaven a noise like a violent rushing wind, and it filled the whole house where they were sitting.

The “wind” (pneuma) and “fire” seem reminiscent of OT “theophanies.” When God would appear to people in the OT, this was often accompanied by wind (1 Kin. 19:11; Isa. 66:15; 2 Sam. 22:16; Job 37:10; Ezek. 13:13) and fire (Ex. 3:2; 19:18; 1 Kin. 18:38-39; Ezek. 1:27).

This wasn’t literal fire or wind. Luke uses the language of simile (“like a violent rushing wind” and “as of fire”). This was an indescribable supernatural event, and Luke tries to capture the miracle as best as he can. The “wind” could also harken back to Genesis 2:7, where God breathes life into the first humans.

(2:3) And there appeared to them tongues as of fire distributing themselves, and they rested on each one of them.

Fire was a symbol of the divine presence in the burning bush (Ex. 3:2), the fiery cloud (Ex. 13:21), Mount Sinai (Ex. 24:17), or the Tabernacle (Ex. 40:38).

(2:4) And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit was giving them utterance.

These “tongues” are different from the charismatic gift of tongues as mentioned in Paul’s letter to the church in Corinth. The “tongues” in Acts 2 refer to human languages, while the tongues in Corinth refer to indescribable speech—perhaps heavenly language (1 Cor. 14:9). This word “utterance” (apophthengomai) is used here as representative of clear and articulate speech (cf. Acts 2:14; 26:25). Indeed, in Acts 26:25, it is contrasted with babbling.

Did the Church exist before Pentecost?

No. Pentecost is the beginning of the existence of the Church. While people came to saving faith in God through grace and apart from works before this time (read Romans 4), before this event, the Church did not exist. This is because the Holy Spirit didn’t indwell believers before this time:

(Jn. 7:38-39) “He who believes in Me, as the Scripture said, ‘From his innermost being will flow rivers of living water.’ 39 But this He spoke of the Spirit, whom those who believed in Him were to receive; for the Spirit was not yet given, because Jesus was not yet glorified.”

(Jn. 14:26) “But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in My name, He will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I said to you.”

(Acts 11:15-17) “And as I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell upon them just as He did upon us at the beginning. 16 And I remembered the word of the Lord, how He used to say, ‘John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.’ 17 Therefore if God gave to them the same gift as He gave to us also after believing in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could stand in God’s way?”

(2:5) Now there were Jews living in Jerusalem, devout men from every nation under heaven.

The text doesn’t say whether these people permanently moved to Jerusalem from other countries, or if they were merely there temporarily for the festival. Both cases surely occurred.

(2:6) And when this sound occurred, the crowd came together, and were bewildered because each one of them was hearing them speak in his own language.

They hear the sound, and then, they listen to the language. The diversity of tongues symbolized an international and multi-ethnic mission.

The term “bewildered” (synechythe) was used at the Tower of Babel (LXX) to refer to how the people would have their languages “confused.” God is rebuilding what was lost at Babel through the Church. However, instead of giving one language to the people, the Christians were able to speak in many languages. This shows God’s love for human culture, which should not be stamped out through the spread of the gospel.

(2:7-8) They were amazed and astonished, saying, “Why, are not all these who are speaking Galileans? 8 And how is it that we each hear them in our own language to which we were born?

The northern Galileans had an unsophisticated accent. Longenecker writes, “Galileans had difficulty pronouncing gutturals and had the habit of swallowing syllables when speaking; so they were looked down upon by the people of Jerusalem as being provincial.”[58] This must have been particularly noticeable, because the Jewish people were able to identify Peter as having a Galilean accent after the death of Christ (Mk. 14:70). To put this in modern terms, imagine a group of hillbillies speaking in fluent French! God chose these non-esteemed people to have the most important role (1 Cor. 1:26-31). In our modern day, Peter Wagner “reports of several missionaries who have been given this gift of speaking in the unknown tongue of the people among whom they were ministering.”[59] Furthermore, the fact that Luke records what all of these foreigners were saying implies that the 120 could not only speak these foreign languages, but also understand them as well.

(2:9-11) Parthians and Medes and Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, 10 Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the districts of Libya around Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, 11 Cretans and Arabs—we hear them in our own tongues speaking of the mighty deeds of God.”

Some think that these “visitors from Rome” went back and started the church in Rome. After all, no apostle had ever been to Rome when Paul wrote the book of Romans. This seems quite likely. After all, roughly 40,000-60,000 Jews lived in Rome, and many Jewish catacombs have been discovered there.[60] This would explain why there was rioting in over “Chrestus” by AD 49 (Suetonius, Life of Claudius 25.4).

(2:12) And they all continued in amazement and great perplexity, saying to one another, “What does this mean?”

They saw a miracle, but they were trying to understand its meaning. It’s possible to see a miracle and not understand what God is trying to communicate through it. In the gospel of John, Jesus performed seven signs (sēmeion), but the bystanders often misinterpreted the meaning. Many people wish to see a miracle, but they don’t realize that their interpretation of the miraculous could be quite confused.

(2:13) But others were mocking and saying, “They are full of sweet wine.”

Miracles can actually have the opposite effect on those with hardened hearts. By suppressing clear evidence, they harden themselves into further rebellion from God. It’s worth noting that many of these skeptics, however, came to Christ after hearing Peter preach.

“You are witnessing the arrival of the Holy Spirit” (Joel 2:28-32).

(2:14) But Peter, taking his stand with the eleven, raised his voice and declared to them: “Men of Judea and all you who live in Jerusalem, let this be known to you and give heed to my words.”

Peter could have been cowardly like the last time he was called to give an account in front of a young slave-girl (Mt. 26:69ff). Instead, he “takes his stand” here in front of the religious leaders. Peter stands with the other apostles (“the eleven”), and this reinforces the fact that in the book of Acts “ministry is almost always done as a team in Acts.”[61]

(2:15) For these men are not drunk, as you suppose, for it is only the third hour of the day. [9 a.m.]

It simply wasn’t common for people to get drunk this early. Though, Longenecker humorously writes, “Unfortunately, this argument was more telling in antiquity than today.”[62] Bruce holds that this was “good humor” on behalf of Peter in refuting this argument.[63]

(2:16-21) “But this is what was spoken of through the prophet Joel: 17 ‘And it shall be in the last days,’ God says, ‘That I will pour forth of My Spirit on all mankind; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams; 18 even on My bondslaves, both men and women, I will in those days pour forth of My Spirit and they shall prophesy. 19 And I will grant wonders in the sky above and signs on the earth below, blood, and fire, and vapor of smoke. 20 The sun will be turned into darkness and the moon into blood, before the great and glorious day of the Lord shall come. 21 ‘And it shall be that everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.’

Peter cites Joel 2:28-32. We reject the notion that Peter was allegorizing OT prophecy, and that this is grounds for an allegorical hermeneutic for eschatology. After all, was Peter giving his first teaching on eschatology? Not at all. This is an evangelistic message—not an eschatological one!

Peter’s purpose in citing Joel 2 is not to show that this was completely fulfilled at Pentecost. Rather, he is showing that it has been partially fulfilled. Consequently, the people should “call on the name of the Lord” and “be saved” before the final judgment. In other words, if the first part was fulfilled (and the people were witnessing its fulfillment), then Peter’s listeners should repent before the rest is fulfilled later in history (i.e. judgment).

(Acts 2:16-21) Does Peter misquote Joel 2:28-32?

“You killed the One who brought the Holy Spirit.”

(2:22) “Men of Israel, listen to these words: Jesus the Nazarene, a man attested to you by God with miracles and wonders and signs which God performed through Him in your midst, just as you yourselves know.”

The men were writing off the miracle and prophetic-fulfillment of Pentecost right before their eyes. Peter notes that they also wrote off the miracles of Jesus. When will they learn? The religious leaders didn’t deny that Jesus performed miracles, but they denied the source or the meaning of these events, even ascribing Jesus’ power to Satan! (Mt. 12:24; Josephus, Antiquities, 18:63-64; Sanhedrin, 43a, 107b; Justin Martyr, Dialogues, 69.7)

(2:23) “This Man, delivered over by the predetermined plan and foreknowledge of God, you nailed to a cross by the hands of godless men and put Him to death.”

The death and suffering of Christ were not a cosmic accident. God planned all of it. This passage blends God’s sovereignty and human responsibility. In Acts 4:26-28, we see these “godless men” were both the Roman leaders and the Jewish leaders.

“Delivered over by the predetermined plan.” The term “predetermined” (hōrizo) means “to separate entities and so establish a boundary… to set limits to” or “to make a determination about an entity, determine, appoint, fix, set” (BDAG). This is the same term used in Acts 17:26 for how God has “determined their appointed times and the boundaries of their habitation.”

“Plan” (boulē) is “mostly used of the divine counsel.”[64] Paul uses the term this way when he told the Ephesian elders that he preached the “whole counsel (boulē) of God” (Acts 20:27). The religious leaders “rejected God’s purpose (boulē) for themselves” (Lk. 7:30). Later, the believers pray that these people had “to do whatever Your hand and Your purpose (boulē) predestined to occur” (Acts 4:28).

“Foreknowledge” (prognōsis) comes from the roots pro (“before”) and ginōskō (“know”).

- In Classical Greek, the term proginōskō meant “to know or perceive in advance, to see the future.”[65]

- The Septuagint uses the verb (proginōskō) three times to refer to knowing the future (Wisdom of Solomon 6:13; 8:8; 18:6), and it uses the noun (prognōsis) twice to refer to knowing the future (Judg. 9:6; 11:19).

- In the NT, the term can be used for “knowing the future” (1 Pet. 1:2; 2 Pet. 3:17; Rom. 8:2; 11:2) or for “knowing them beforehand” (i.e. known in the past; Acts 26:5; 1 Pet. 1:20).

“You nailed to a cross by the hands of godless men and put Him to death.” Even though all of this was orchestrated according to God’s plan, the people themselves are held responsible.

(2:24) “But God raised Him up again, putting an end to the agony of death, since it was impossible for Him to be held in its power.”

“Putting an end to the agony of death.” This must refer to physical death, which Jesus abolished death at the Cross. This is already-not-yet language. Jesus already ended the agony of death through his resurrection, but this is not yet fulfilled until the New Heavens and Earth.

“But God raised him from the dead” (Pss. 16; 110; 132).

(Acts 2:25-28) “For David says of Him, ‘I saw the Lord always in my presence; for He is at my right hand, so that I will not be shaken. 26 ‘Therefore my heart was glad and my tongue exulted; moreover my flesh also will live in hope; 27 because You will not abandon my soul to Hades, nor allow Your Holy One to undergo decay. 28 ‘You have made known to me the ways of life; you will make me full of gladness with Your presence.’”

Peter cites Psalm 16:8-11 to demonstrate that God promised that the “Holy One” (i.e. the Messiah) would not “decay” in death. 36 hours in the tomb was not long enough for Jesus’ body to decay. Paul quotes Psalm 16 to defend the reality of the resurrection as well (Acts 13:35).

(Acts 2:25-28) Why does Peter cite Psalm 16:10 to demonstrate the resurrection of Jesus?

(2:29-31) “Brethren, I may confidently say to you regarding the patriarch David that he both died and was buried, and his tomb is with us to this day. 30 And so, because he was a prophet and knew that God had sworn to him with an oath to seat one of his descendants on his throne, 31 he looked ahead and spoke of the resurrection of the Christ, that He was neither abandoned to Hades, nor did His flesh suffer decay.”

Peter notes that this passage cannot be autobiographical, because David’s body did decay (v.29). While we do not know the location of David’s tomb today, it’s likely that they knew the location in the first-century. The tomb was known at least in the days of Nehemiah (Neh. 3:16), and surely in Peter’s day as well. Josephus states that John Hyrcanus stole 3,000 talents of gold from David’s tomb in 135 BC, and later, Herod tried to loot David’s tomb as well (Antiquities 13.249; Wars of the Jews 1.61). Because they could witness David’s decaying body, Peter argues that David was a “prophet” who predicted the future about the Messiah (v.30). Peter further cites Psalm 132:11 to demonstrate that the Davidic Covenant predicted someone in the line of David who would be the Messiah (cf. 2 Sam. 7:12-16; Ps. 89:3ff; 35-37). Incidentally, this refutes the idea that the psalms are merely poetry. Some of them are clearly prophetic according to the NT.

(2:32) This Jesus God raised up again, to which we are all witnesses.

Peter states that the apostles are direct eye-witnesses of this predicted resurrection.

(2:33) “Therefore having been exalted to the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, He has poured forth this which you both see and hear.”

Because Jesus is our mediator, we now have the gift of the Holy Spirit. To paraphrase Peter, he seems to be saying, “Do you think it was just a coincidence that the coming of the Holy Spirit came just after the death and resurrection of Jesus? No way! This is all fulfilling prophecy!”

(2:34-35) “For it was not David who ascended into heaven, but he himself says: ‘The Lord said to my Lord, “Sit at My right hand, 35 Until I make Your enemies a footstool for Your feet.”’

Peter cites Psalm 110 to support the ascension of Jesus. God didn’t offer the invitation to David to sit at his right hand—only David’s “Lord.”

“Until I make your enemies a footstool.” Of course, Jesus hasn’t taken over his enemies yet, but he will. In context, the mention of “enemies” would surely have made Peter’s listeners tremble at the thought that they were culpable for the death of Christ.[66]

(2:36) “Therefore let all the house of Israel know for certain that God has made Him both Lord and Christ—this Jesus whom you crucified.”

If Israel just crucified her Messiah, what will happen to Israel? Instead of preaching a message of judgment, Peter preaches a message of incredible hope and forgiveness.

Peter calls Jesus “Lord” (kyrios). Fernando writes, “In this speech kyrios is used for Jesus in ways that were used for God in the LXX (see vv. 20-21); moreover, Jesus as Lord has taken on divine functions, such as pouring out the Spirit (v. 33) and being the object of faith (v. 21). Note how in verse 36 Jesus is called Lord while in verse 39 God continues to be called Lord.”[67]

(2:37) Now when they heard this, they were pierced to the heart, and said to Peter and the rest of the apostles, “Brethren, what shall we do?”

Peter’s preaching was convincing because it was convicting. His teaching was “effective, not only persuading his hearers’ minds but convicting their consciences.”[68] The people were “pierced to the heart.” Bock states that this verb “refers to a sharp pain or a stab, often associated with emotion.”[69] The preaching of the word can have this effect: “For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any two-edged sword, and piercing as far as the division of soul and spirit, of both joints and marrow, and able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb. 4:12).

“Turn to Christ and be forgiven!”

(2:38) Peter said to them, “Repent, and each of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Repentance means “a change of mind.” Elsewhere, we read of a “repentance toward God” (Acts 20:21). Repentance shouldn’t lead to guilt, but to grace.

(Acts 2:38) Is baptism necessary for salvation?

(2:39) “For the promise is for you and your children and for all who are far off, as many as the Lord our God will call to Himself.”

The term “far off” (makran) is later used to refer to the Gentiles: “Go! For I will send you far away to the Gentiles” (Acts 22:21). Just like Acts 1:8, this could foreshadow how the gospel would reach the Gentiles.

Does this support infant baptism? Peter writes that this promise is for “your children.” But this doesn’t support baptizing infants. The term “children” (teknois) has a wide range of age—far beyond infancy. In context, the “children” need to be old enough to “believe” and “repent” (v.38). Earlier, Peter referred to children who could “prophesy” (v.17). Of course, “in neither case are infants obviously involved.”[70] Instead of infant baptism, this statement is a promise that later generations will benefit from what Jesus accomplished: The promise is for the children, but Peter doesn’t specify when they will receive it (anymore than those who are “far off” from Israel).

(2:40) And with many other words he solemnly testified and kept on exhorting them, saying, “Be saved from this perverse generation!”

This speech is not exhaustive. Surely, Peter had more to say. The NIV translation states that Peter “warned them and he pleaded with them.” Jesus referred to our current age as a “corrupt generation” (Mt. 16:4; 17:17), as did Paul (Phil. 2:15).

How did the people respond to Peter’s teaching?

(2:41) So then, those who had received his word were baptized; and that day there were added about three thousand souls.

Considering the fact that this was Peter’s first recorded teaching, Peter didn’t do a bad job! Millard Erickson comments, “One simply cannot account for the effectiveness of those early believers’ ministry on the basis of their abilities or efforts. They were not unusual persons. The results were a consequence of the ministry of the Holy Spirit. Students in a homiletics class were required to prepare sermons based on various sermons recorded in the Bible. When the students came to Acts 2, they discovered that Peter’s address at Pentecost is not a marvel of homiletical perfection. All of them were able to prepare sermons that were technically superior to that of Peter, yet none of them expected to surpass his results. The results of Peter’s sermon exceed the skill with which it was prepared and delivered. The reason for its success lies in the power of the Holy Spirit.”[71]

Is this number of 3,000 converts an exaggeration? No. It’s quite possible for a crowd of this size to hear Peter and come to faith. After all, John Wesley and George Whitefield preached to far bigger crowds in the open air. Moreover, the other 120 people—particularly the other eleven apostles—could have led people to Christ as well, baptizing these people as a result. After all, this narrative opened with Peter “taking his stand with the eleven” (Acts 2:14). If all 120 people helped with the follow up work, then this would result in only 25 people being baptized per person. Furthermore, since this was during the Passover, the population of Jerusalem swelled to several hundred thousand. Polhill writes, “Jerusalem had an ample water supply, the temple area was vast and would accommodate 200,000 or more…, and the resident population of Jerusalem has been estimated at 55,000, swelling to 180,000 during pilgrim festivals.”[72]

In conclusion, the numbers of people were there to listen, and the Christian workers were there to baptize these brand-new converts. The only thing difficult for us to believe is that this many people would give their lives to Christ. But surely this says more about our own unbelief in the power of the Holy Spirit, than in the historical account itself!

Four essentials of fellowship

We might wonder how 120 people were able to lead these 3,000 brand new converts. This section is brief, but it gives us a window into what this looked like. Rather than calling this “follow up,” Fernando refers to this section as “follow-through care,”[73] describing how these leaders looked after these brand-new Christians. In this picture of the early church, we have what Bruce calls “an ideal picture of this new community.”[74] We agree. This is a model for us to emulate as a church.

(2:42) They were continually devoting themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer.

The early church “devoted” (proskartereō) themselves to four practices. Longenecker writes, “The verb translated ‘devoted’ (proskartereō) is a common one that connotes a steadfast and singleminded fidelity to a certain course of action.”[75] On what did the early Christians focus? We see key areas:

(1) “to the apostles’ teaching.” Jesus had just spent 3.5 years teaching the disciples. Now it’s their turn. Moreover, Jesus held Bible studies for 40 days after his resurrection, and concluded by instructing the apostles to “teach” new believers all that he had instructed them (Mt. 28:20). This teaching had authority, and later, the writings of the apostles became Scripture. Bruce writes, “This teaching was authoritative because it was the teaching of the Lord communicated through the apostles in the power of the Spirit. For believers of later generations the New Testament scriptures form the written deposit of the apostolic teaching.”[76]

(2) “to fellowship.” This is the only time this word (koinonia) is used in Luke’s writings.[77] It is a favorite term of Paul’s. It comes from the term “common” (koine), which means “sharing.”

(3) “to the breaking of bread.” Though the English translation doesn’t capture this nuance, this passage contains the article before “bread” (“the bread”). In verse 46, the article isn’t there (“breaking bread from house to house”). Moreover, since the other three activities have direct spiritual connotations, it would seem to follow that this one does as well. This leads Bruce,[78] Fernando,[79] and Polhill[80] to believe that this is referring to the practice of the Lord’s Supper. We tend to agree with this view. Others, however, argue that the expression is only used one other time to refer to a regular meal (Lk. 24:35), so this could simply refer to sharing meals together.

(4) “to prayer.” Here we see the great theme of prayer being expressed as central to the Christian community.

What were the consequences of these four essentials?

(2:43) Everyone kept feeling a sense of awe; and many wonders and signs were taking place through the apostles.

The “awe” (phobos) refers to astonishment (cf. Acts 5:26). It is associated with “comfort” (Acts 9:31), rather than fear (1 Jn. 4:18).

(Acts 2:44-45) Were the early Christians the first communists (c.f. 4:32)?

(Acts 2:44-45) And all those who had believed were together and had all things in common; 45 and they began selling their property and possessions and were sharing them with all, as anyone might have need.

This experience of God’s love led to radical love for others. Fernando writes, “The important point is that the fellowship touched the pocketbook too!”[81]

(2:46) Day by day continuing with one mind in the temple, and breaking bread from house to house, they were taking their meals together with gladness and sincerity of heart.

They met daily. They were like-minded. They met in house churches. They were eating together. This produced a generous and sincere spirit in the people. Fernando argues that this generic “breaking of bread” probably included the Lord’s Supper—in addition to shared meals. In other words, both are in view.

(2:47) Praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord was adding to their number day by day those who were being saved.

There was something about this community that the non-Christian culture could see was attractive. They enjoyed the generosity which the Christians provided. Could the same be said today in Christian community?

Theologian John Polhill concludes this section of Acts with these words, “It could almost be described as the young church’s ‘age of innocence.’ The subsequent narrative of Acts will show that it did not always remain so. Sincerity sometimes gave way to dishonesty, joy was blotched by rifts in the fellowship, and the favor of the people was overshadowed by persecutions from the Jewish officials. Luke’s summaries present an ideal for the Christian community which it must always strive for, constantly return to, and discover anew if it is to have that unity of spirit and purpose essential for an effective witness.”[82]

What did God do to prepare and empower the launch of his church?

God predicted this and prefigured it through OT foreshadowing. In fact, he planned it all out to the day of Pentecost (v.2).

God communicated to all people—not just Jews in Jerusalem (v.6). He was breaking boundaries.

God used regular people to lead his movement (vv.7-8). The disciples were Galileans.

God performed miracles get people’s attention and draw a crowd, but he empowered a speaker like Peter explain the meaning and message behind the miracles. Miracles in and of themselves were insufficient (v.13).

God led Peter to begin his preaching with Jesus (v.22), and ends his preaching with Jesus (v.36).

God didn’t leave these Christians to fend for themselves after coming to faith. God led a system of follow up with these believers through Bible teaching, fellowship, gratitude, and prayer (v.42). They met frequently in small and large groups (v.46), and this led to further growth in the church.

Questions for Reflection

Read verses 14-36. What do we learn about the basics of the gospel message from Peter’s teaching?

What evidence does Peter give for his message about Jesus? Do you find this evidence persuasive? Would his original audience have found this persuasive?

Read verses 41-47. What do we learn about Christian community from these passages? How does this compare to modern churches today? How does this picture compare to your current church?

Acts 3 (Healing the Disabled man)

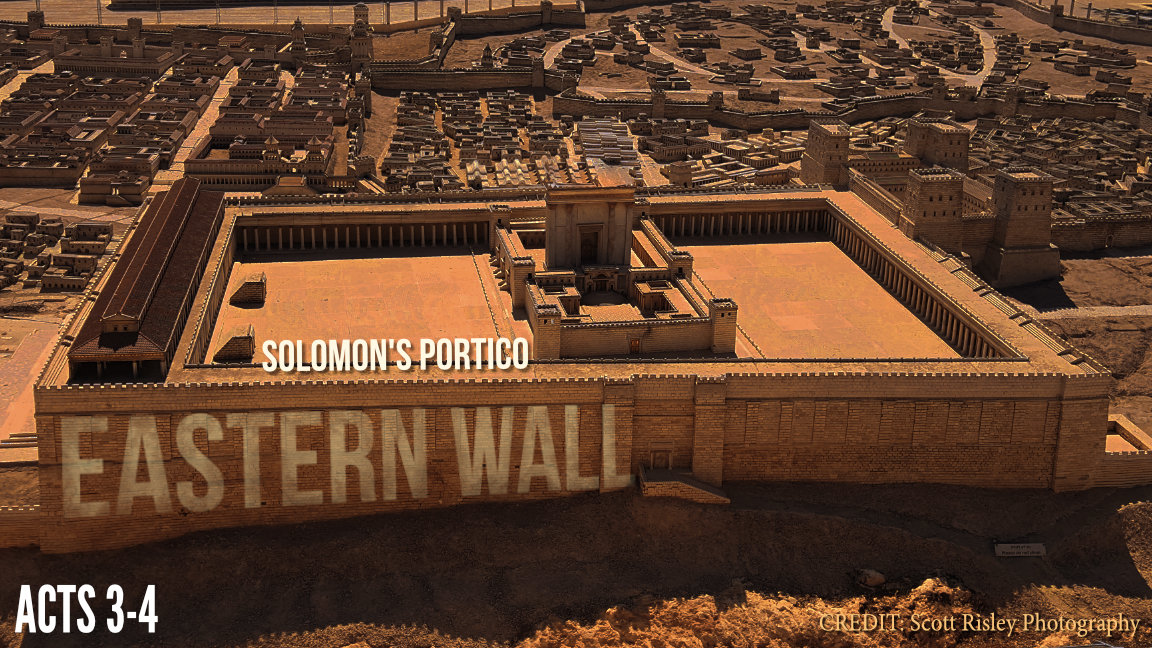

Luke already mentioned that the apostles were performing many miracles among the people (Acts 2:43) in the Temple (Acts 2:46). Here we read about one particular miracle in the Temple precincts that was performed by Peter and John.

(3:1) Now Peter and John were going up to the temple at the ninth hour, the hour of prayer.

The first hour of the day for the Jewish people was 6am. So, the ninth hour is 3pm. The afternoon was a busy time of day at the Temple, and this could be why Peter and John went there to share their faith.[83] Before they came to faith, these two men had been friends and business partners (Lk. 5:10). Now, God is using them as coleaders in Christian work.

(3:2) And a man who had been lame from his mother’s womb was being carried along, whom they used to set down every day at the gate of the temple which is called Beautiful, in order to beg alms of those who were entering the temple.

This beggar had been physically handicapped since birth, and he was 40 years old at this point (Acts 4:22). For the first four decades of his life, he knew nothing other than shame, poverty, and public humiliation. He was at the total mercy of other people’s generosity. He sat at the eastern gate of the Temple.

What is the gate called “Beautiful”? We do not possess records in Jewish literature of a gate called “Beautiful.” After the third century AD, this gate was associated with the Shushan gate, but this is unlikely. The Shushan gate was right next to a steep cliff above the Kidron Valley, and it wouldn’t have been a good access point for a disabled man to enter. The Mishnah, however, refers to another entrance near the sanctuary itself called the Nicanor gate (cf. m. Middôṯ 2.3). Josephus states that this gate was covered with “Corinthian brass and greatly excelled those that were only covered over with silver and gold” (Wars of the Jews 5.201). This would explain why they called this the “Beautiful” gate, and this is a more likely site than the Shushan gate. We agree with Bruce[84] and Polhill[85] that this is the gate to which Luke is referring.

“In order to beg alms of those who were entering the temple.” This man had his friends strategically place him by the entrance to the Temple. Since many people were in town for the festivals in Jerusalem, this was a perfect location for a beggar. We might compare this to a person collecting money for the Salvation Army around Christmas time. The man placed himself here to receive money. But what he received was something far greater…

(3:3) When he saw Peter and John about to go into the temple, he began asking to receive alms.

He’s expecting some spare change, but instead, he gets his life changed!

(3:4-5) But Peter, along with John, fixed his gaze on him and said, “Look at us!” 5 And he began to give them his attention, expecting to receive something from them.

Apparently, the man wasn’t even looking people in the eye. He was so downcast and filled with despair that he was looking down at the ground as he raised his hand for money. Marshall writes, “What could have been simply the occasion of mechanical charity is turned into a personal encounter as the lame man and the apostles look intently at one another.”[86] Peter and John confer dignity on this man as they encounter him. Polhill writes, “Perhaps [the disabled man] expected a display of unusual generosity. Would this be his day? Yes, it would be, but not as he might think.”[87]

(3:6) But Peter said, “I do not possess silver and gold, but what I do have I give to you: In the name of Jesus Christ the Nazarene—walk!”

“I do not possess silver and gold.” The apostles lived simple lives, so Peter doesn’t have money to give him. The disabled man must’ve been disappointed to hear these initial words. In this man’s mind, silver and gold were the answer to his problems.

“In the name of Jesus Christ the Nazarene.” By calling on the “name” of Jesus, Peter was calling on Jesus’ authority and power. Longenecker writes, “In Semitic thought, a name does not just identify or distinguish a person; it expresses the very nature of his being. Hence the power of the person is present and available in the name of the person.”[88] Peter appeals to Jesus, but Jesus never appeals to a higher name than his own because Jesus has the “name which is above every name” (Phil. 2:9). Marshall writes, “Jesus himself had no need to appeal to a higher authority such as the name of God.”[89]

“Walk!” The man wasn’t given what he wanted (“silver and gold”), but God gave him wanted he needed.

(3:7-8) And seizing him by the right hand, he raised him up; and immediately his feet and his ankles were strengthened. 8 With a leap he stood upright and began to walk; and he entered the temple with them, walking and leaping and praising God.